A one-minute video clip of Martin Luther King Jr. speaking on the University of Miami’s Coral Gables Campus in 1966.

News clippings and photographs of a student-led sit-in staged in University President Henry King Stanford’s office to demand the enrollment of more Black students, the creation of African American history courses, and the hiring of Black professors to teach them.

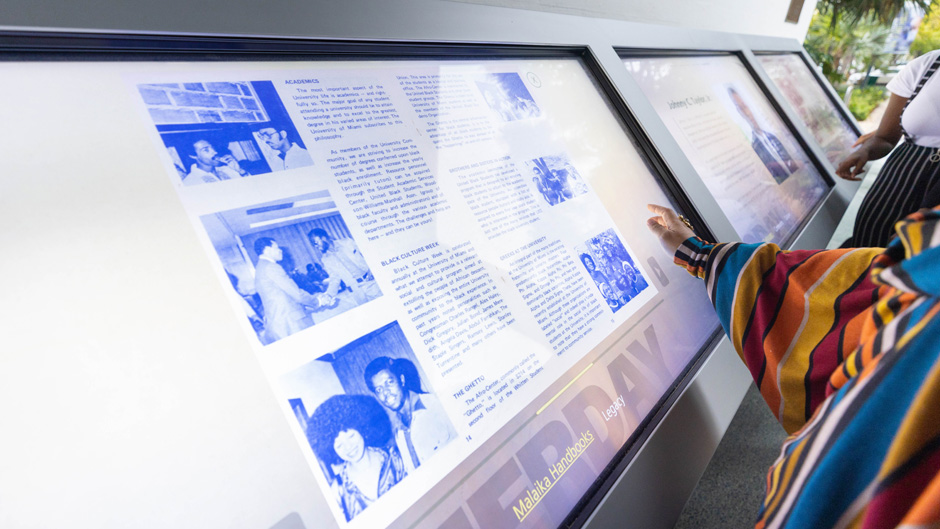

Pages from the Malaika handbooks, guides produced by the United Black Students organization during the 1970s to help underrepresented students navigate college life during the early years of desegregation at the University.

These are just a sample of the trove of items—all in digital and video format—now featured in a new University of Miami Libraries exhibit that chronicles the history of the institution’s first Black graduates.

The Taylor Family/UTrailblazers Experience features an interactive three-screen kiosk with touchscreen technology that allows users to scroll through hundreds of photographs, documents, newspaper articles, film footage, bios, and other historical artifacts related to the years just after the University’s Board of Trustees voted in 1961 to admit qualified students without regard to race or color beginning in the summer of that year.

The idea for the exhibit was first conceived by the Black Alumni Society in 2012, following the University’s 50-year anniversary marking desegregation. Sparked by their own curiosity, a group of alumni volunteers, including Denise Mincey-Mills, Phyllis E. Tyler, and Antonio Junior—all 1979 graduates of the University—began to unearth the stories and struggles of the first Black students.

Their efforts evolved into the First Black Graduates Project which later became known as UTrailblazers. When Johnny C. Taylor Jr., an alumnus of the School of Communication and vice chair of the University’s Board of Trustees, learned about the UTrailblazers project, he stepped forward with a generous donation to turn the dream of a permanent memorial into a reality. Taylor’s gift is part of the University’s Ever Brighter: The Campaign for Our Next Century.

“Johnny Taylor is lifting stories that are an incredibly important part of the University of Miami’s history,” said Josh Friedman, senior vice president for development and alumni relations. “We are extremely grateful to him and his family for making this extraordinary commitment.”

The exhibit has a two-pronged purpose, said Taylor, who is president and CEO of the Washington, D.C.-based Society for Human Resource Management, and whose family history is deeply embedded in South Florida and in the University of Miami. “The first Black graduates of this institution probably didn’t consider themselves pioneers, but they were. This exhibit is a way of looking back in history to honor them, to show appreciation for the path they ultimately paved for not only people like me but also current and future generations of students,” Taylor explained.

“Equally as important,” he continued, “is that the exhibit demonstrates to all segments of society that this University is truly capable of practicing true diversity and inclusion without sacrificing quality and competitiveness.”

Mincey-Mills played a key role in helping to locate items for the exhibit, visiting University Archives in the Richter Library on several occasions to assist in the search for materials. “We wanted to uncage our history,” she said. “For me and, I’m sure, for other Black University alumni, this exhibit is our National Museum of African American History and Culture. It is that important to us.”

Located in the Dooly Memorial Classroom Building breezeway, which is now known as the Johnny C. Taylor Jr. Breezeway in honor of his family’s historic gift, the exhibit is divided into three time periods—yesterday, today, and tomorrow—allowing users “to experience the arc of the experiences of the Black community at the University,” said Roxane Pickens, librarian assistant professor and director of the Learning Commons at University Libraries, who led the exhibit’s curation.

One of the exhibit’s most informative features: a timeline that outlines major milestones in the Black student experience at the University—such as 1962, when Benny O’Berry became the first Black student to graduate from the University, earning a bachelor’s degree from the School of Education.

While the bulk of material for the exhibit came from collections already housed at the Richter Library, other items were obtained from University library branches at the Miller School of Medicine, Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, and other schools and colleges, according to Pickens.

“An exciting aspect of this digital exhibit is the desire of University of Miami Libraries to engage our constituents in meaningful and accessible ways,” said Charles Eckman, dean of libraries and University librarian. “The collaborative work of Dr. Pickens, Nick Iwanicki [University archivist], and Marcia Heath [archives specialist], and so many others in the libraries on this project demonstrates the tremendous capacity of libraries to preserve, digitize, and re-create content in ways that build shared understanding.”

Iwanicki echoed those sentiments, saying libraries are becoming not just content providers but also content creators. “We’re engaging with audiences in ways that libraries previously wouldn’t have thought about,” he said. “There aren’t many exhibits, even in the museum world, that are designed to grow over time.”

Pickens called the UTrailblazers Experience a “living exhibit,” one infused with technology that will allow users, such as a graduate from the 1960s and 1970s, or a current student, to share their own stories.

“It will never become stale or dated like pictures on a wall,” Taylor said.