Between working on her master’s degree thesis and creating new technology for homes of the future, Olha Khymytsia keeps track of the almost-daily entries to a heartrending list: historic buildings and landmarks in her homeland of Ukraine that have been damaged or destroyed by Russian bombs and missiles.

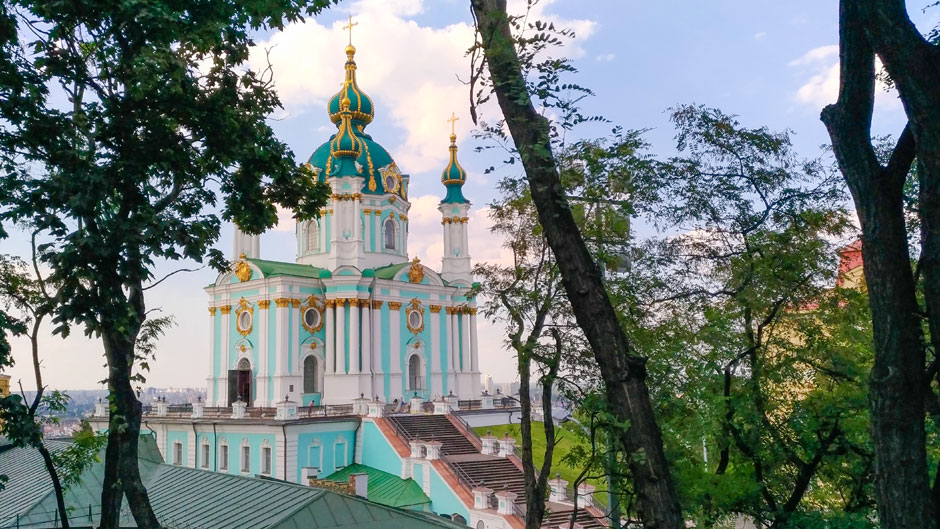

From churches in Donetsk to a library in Kharkiv to a monument in Kherson, nearly 250 structures of historical significance are on the list, compiled and placed on the internet by Ukrainian citizens who are documenting the destruction of their country.

Khymytsia, a graduate assistant at the University of Miami School of Architecture, looks at the list at least once a day.

She wants the world to know that along with the ever-growing humanitarian crisis caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, her homeland’s architectural heritage is at risk of being erased, as its buildings, landmarks, and public squares continue to be reduced to rubble by Russian rockets.

“Architecture helps make us different. It’s one of the most effective ways of representing a country’s culture, its history,” said Khymytsia, who was born and raised in the western Ukrainian city of Lviv. “Until now, we may have taken that for granted. But now, I believe we’re all realizing just how important architecture is and that it should be preserved.”

Professor of architecture Jorge L. Hernandez echoed her sentiments. “Architectural heritage is about memory and history,” he explained. “And those two things are and have always been embodied in places. That’s why we are so drawn to different sites.”

Ukraine is home to seven UNESCO World Heritage Sites, all of which Khymytsia has visited. And while none appears to have been damaged in the war, scores of other cultural sites have been harmed, according to the United Nations-run agency.

Russian artillery, for example, damaged a menorah at the Drobytskyi Yar Holocaust memorial complex in eastern Ukraine about a month after the war started, according to Ukraine’s ministry of defense. And in the early stages of the conflict, invading forces reportedly burned the Ivankiv Historical and Local History Museum to the ground, destroying the 25 paintings by Ukrainian folk artist Maria Prymachenko.

The attacks, if deliberate, would be violations to the provisions of the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict, to which Russia, ironically, is a signatory.

“It’s the eradication of our culture, our history,” Khymytsia said of the attacks.

But she remains optimistic, hoping for the war’s end and a Ukrainian victory. “Only time will tell,” she said.

When armed conflict does cease, the 24-year-old Khymytsia, who as a little girl would watch an American-made home makeover show on Ukrainian television, wants to return to her homeland and use her architectural skills to help rebuild it.

She believes there is an opportunity to not only replace what has been destroyed but also to improve upon it. “We’ll have the chance to modernize the country in certain areas.”

To help in its rebuilding, Ukraine will have several examples to follow of countries that reinvented themselves after the ravages of war reduced their infrastructure to rubble.

“There’s Poland, Ukraine’s western neighbor, with its wonderful capital city of Warsaw,” said Hernandez, an authority on architectural history who helped restore a dozen churches in Cuba. “Warsaw is a fantastic example. It was reborn after essentially being reduced to rubble by Nazi Germany. It was the will of the people to recreate the urban landscape and skyline of Warsaw. And there are other case studies, many of them quite well known.”

As for now, Khymytsia continues to keep abreast of the latest developments in the war by watching television coverage and reading newspaper articles.

Her mother and father still live in Lviv, which until recently had been largely unaffected by the war. That changed on April 18, when the city reported its first wartime deaths after Russian missiles hit a military warehouse and a commercial service station two milesfrom Khymytsia’s home. Among the dead: an acquaintance of one of her best friends.

“But out of the ashes and crumbled concrete,” Khymytsia declared, “Ukraine will rise again.”