The patients arrived at the largest emergency hospital in Lviv by the dozens, transported hundreds of miles via ambulance and other vehicles from the eastern region of war-torn Ukraine. Seventy casualties arrived on one day, 30 on another, nearly 100 on yet another occasion.

Most were civilians—men and women with the worst of injuries: a 40-year-old woman whose arm was so badly mutilated it may have to be amputated; a man with shrapnel wounds to his arms, back, and feet; and a woman with a severely fractured skull.

Their wounds were quite familiar to trauma surgeon Enrique Ginzburg. After more than 30 years working at one of the nation’s top trauma centers, he’s seen his fair share of life-threatening injuries.

But one difference stood out. “These were large projectile wounds. So, the injuries to the extremities, chest wall, and abdominal areas were much more massive,” said Ginzburg, a professor of surgery at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and trauma medical director and chief of surgery at Ryder Trauma Center at Jackson South Medical Center.

He and two other physicians—John Holcomb, a retired Army colonel who is now a professor of trauma and acute care surgery at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, and Steven Wolf, professor and chief of burn and trauma surgery at the University of Texas Medical Branch—had traveled nearly 6,000 miles from Miami to the Lviv Clinical Emergency Hospital to mentor and train the young Ukrainian trauma surgeons who are treating civilian casualties of the now two-month-old Russia-Ukraine war.

Many of the surgeons they mentored only recently completed their residencies, and ever since Russian forces invaded Ukraine on Feb. 24, they have been dealing with an influx of serious war injuries. “The hospital’s director of trauma, a position at U.S. medical centers that’s typically occupied by someone in their late 40s or even early 50s, is only 33,” Ginzburg said. “But he and the other Ukrainian surgeons are all good, exceptionally good. And they’re doing a wonderful job.”

Ginzburg deployed to the region in early April as a volunteer physician with the Global Surgical and Medical Support Group (GSMSG), a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit of trauma surgeons and other health care providers who train doctors, nurses, and other medical personnel working in high-threat conflict areas around the world. Buffalo, New York, surgeon Aaron Epstein founded the organization.

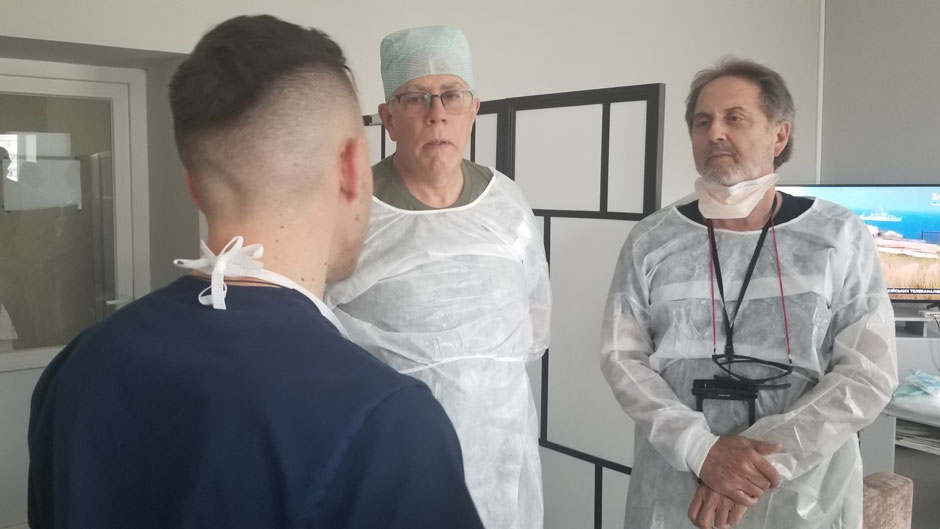

During Ginzburg’s stint at the 1,200-bed hospital, he, Holcomb, and Wolf toured the wards of the wounded, looking in on patients and sharing with their young Ukrainian counterparts their knowledge of treating combat injuries.

And that knowledge is extensive. The doctors who volunteer through GSMSG practice emergency and trauma medicine in some of the leading hospitals in the U.S. and have deployed to hot spots from Afghanistan and Iraq to Syria and Somalia.

Before the coronavirus pandemic hit, Ginzburg spent a week at a medical facility in Kurdistan. And in 2010, as part of renowned Miller School neurosurgeon Barth Green’s Project Medishare, he helped establish and operate a 250-bed field hospital in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, after a 7.0-magnitude earthquake devastated that country, killing tens of thousands of people and injuring a multitude of others.

“When this came about, I wanted to help,” he said of the opportunity to go to Ukraine.

He was still in the first week of a 14-day vacation at the time and wrestled with the idea of whether he should go. “I spoke to my wife and said, ‘What am I going to do? Just stay here in Miami for another week?’ ” recalled Ginzburg, whose grandparents emigrated from Europe in the 1940s—his grandfather from Kyiv and his grandmother from Poland, both making new lives for themselves in Cuba.

“In Ukraine, I knew I’d have a chance to do something meaningful, both personally and perhaps to set an example,” he said.

So, he decided to go, reaching out to Epstein, who was already in Lviv, to work out the logistics.

Along with his wife, Barbara, a licensed occupational therapist, and Holcomb and Wolf, Ginzburg flew into Warsaw, then took a regional flight to Rzeszów, where members of the 82nd Airborne Division were stationed.

From there, GSMSG security personnel transported them from the Polish border to a secure location in Ukraine, clearing a multitude of checkpoints.

Once in Lviv, they hit the ground running. From visiting patients to observing surgical procedures in the operating room to discussing administrative details such as mass casualty triage, equipment, and staffing, their days at Lviv Clinical Emergency Hospital started early and ended late.

They lectured to Ukranian medical students on combat casualties. And they met with the mayor of Lviv, Andriy Ivanovych Sadovyi; the World Health Organization’s regional director for Europe, Hans Henri P. Kluge; and Ukraine’s minister of health, Viktor Lyashko.

At last count, close to 280 hospitals in Ukraine have been damaged, with 19 of them destroyed. As such, the needs of Lviv Clinical Emergency Hospital and a local burn center are immense. During meetings with high-ranking hospital officials, Ginzburg and his colleagues discussed how GSMSG could help Ukraine meet those needs.

Among the projects they discussed: developing a telemedicine infrastructure that would expand throughout the country to eastern-front hospitals and clinics that are still standing; instituting a two-week ongoing rotational schedule for trauma surgeons at several Lviv-area hospitals; and providing extensive training for the hospital’s administration and trauma network.

During their stay, Lviv had been largely spared from Russian attacks, making the city a refuge for people fleeing the violence. But still, occasional air-raid sirens rang out, though no bombs or missiles ever hit the center of town while Ginzburg and the others were at the hospital, he said.

The injured civilians with whom Ginzburg spoke during patient rounds had received initial medical help at health care facilities in the east and were transferred to Lviv for definitive care. One case in particular hit him hard, he admitted.

Olga Zhuchenko, who operated a grocery store in Ukraine’s Luhansk region with her husband, had been sitting in her apartment when seven Russian bombs hit her neighborhood, destroying everything she owned.

“She seemed so vulnerable,” Ginzburg said of the 40-year-old woman. “It was just heartbreaking that one minute she was sitting in her home, and then a massive weapon almost takes her life.

“But we’re amazed at the incredible resolve of the patients we saw,” Ginzburg continued. “They’re very strong emotionally. What they told us was that even if Putin destroys the whole country, they’re not going to give up. They’re not going to become slaves.”