The Colombian presidential election is heading into a runoff on June 19 in a match that has catapulted a left-wing candidate into the presidential race.

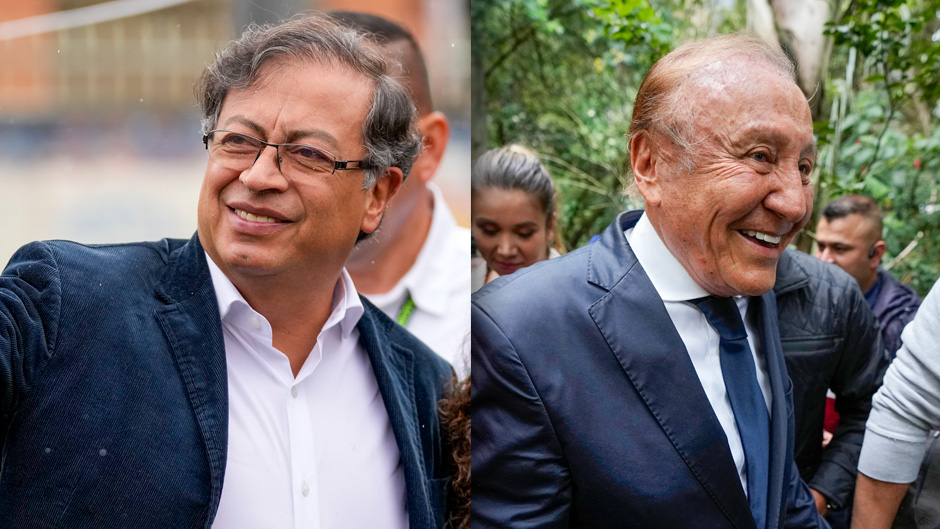

Gustavo Petro, a former guerrilla member and past mayor of Bogota who is presently a senator, claimed 40 percent of the vote in the first round of elections held on May 29. Rodolfo Hernández, an engineer and businessman who used mostly social media to campaign, took about 28 percent of the votes.

Petro, a former member of the M-19 guerrilla group, has gained popularity with a platform that promises to overhaul Colombia’s economy, curb poverty, implement practices to address climate change, and tax wealthy landowners.

“The vote is a result of a growing frustration by the electorate with the government that has not promoted social development,” said John Twichell, lecturer and director of Latin American Studies in the University of Miami College of Arts and Sciences. “The government is not fulfilling the people’s needs,” he added.

“Colombians are tired,’’ said Colombian-born Ómar Vargas, associate professor of Spanish in the Michele Bowman Underwood Department of Modern Languages and Literatures. “They lost hope in the government. It started a few years back when the government tried to impose some unpopular and unfair tax reform laws.”

There were major protests against those tax reforms that lasted months and turned extremely violent in 2021. Both Twichell and Vargas agreed that the COVID-19 pandemic also exacerbated the country’s underlying problems.

Colombia now has an unemployment rate that hovers near 12 percent. And an increase in violence by armed guerrilla groups tied to drug trafficking is having a devastating effect on the country’s civilians. Although a 2016 Peace Accord with the guerillas was meant to end most of the conflict, the pact has not been fully implemented, said Twichell.

“The limited and unbalanced implementation of the Peace Accord has left many rural areas insecure and open for the informal, illicit economy to operate throughout the territory of Colombia,” said Twichell.

The country also has one of the worst distributions of wealth in the world, according to Vargas. “There is a lot of poverty,” he emphasized.

Petro has promised that his first act as president would be to implement a state of emergency to address hunger. Almost 16 million people in Colombia live on two meals or fewer per day, according to a Colombian association of food banks.

Many critics fear that Petro would impose other presidential orders and that he could turn Colombia into another Nicaragua, Venezuela, or Cuba, Vargas noted.

Twichell, however, said that he doubts that Petro would go the route of those authoritarian countries.

“I do not believe he could do that because there are functioning democratic institutions that exist to prevent Petro or anyone else from doing so,” he said.

Petro’s Historic Pact coalition would need to pursue consensus building in a non-majority congress in order to pass legislation. Moreover, the Central Bank is independent, and Colombia’s judicial system is autonomous and is set up to provide checks and balances to the executive branch regardless of who is in power, Twichell pointed out.

Vargas, like many other Colombians, does not believe that Petro stands a chance at winning the presidential post. Instead, he purports that the candidate who will get the job is Hernández—a colorful conservative that Vargas describes as a “very folkloric, Colombian version of Donald Trump.”

The third highest votes in May’s election, with 24 percent, went to right-wing candidate Federico Gutiérrez, who already has given his support to Hernández.

According to a survey by La FM, a Colombian radio station, Hernández is ahead in the polls with an eight-point lead. About 52 percent of those contacted said they will vote for him in the runoff and 44 percent stated that they will support former guerrilla member Petro.

“Colombians are very conservative,” Vargas said. “If you add all the numbers of people who voted for other candidates besides Petro, it will exceed the 40 percent that voted for him.”

The unconventional Hernández is running what he has shared as an “anti-corruption platform.” Most of his campaign was carried out on social media, which earned him the title “king of TikTok.” He refused to participate in debates with the other candidates.

His agenda is one of conservative law and order but he wants to reestablish consular and trade relations with Nicolás Maduro’s socialist regime in Venezuela. According to news reports, Hernández also has proposed rewarding citizens who provide evidence of corruption among state officials.

Ironically, Hernández is facing corruption charges and is scheduled to go to trial in July. He is accused of improperly awarding a business contract while he was mayor of Bucaramanga. The suit alleges that Hernández’s son benefited financially from the contract. Hernández denies any wrongdoing.

Twichell maintained that any one of the two candidates could win the presidency. He said some voters may give a nod to Petro because he is the more experienced politician, and he is also addressing many of the needs of the young and disenfranchised.

On the other hand, Hernández touts the fact that he is not part of the political establishment of the country. And the candidate pointed out that as a businessperson, he knows how to resolve many of the existing problems.

“There is 20 percent of the vote up for grabs,” said Twichell. “It will come down to whose narrative wins out in the next few weeks before the election.”