Brazil will vote to elect a new president on Oct. 2. Whoever ends up in the presidential seat inherits a host of challenges: high inflation, climbing unemployment, and extreme polarization of the electorate.

The two top contenders are Jair Bolsonaro, the incumbent president, and former president Luis Inácio da Silva.

Bolsonaro is a right-wing former military officer who came to power in 2019. Although early in his tenure he tackled a failing economy, Bolsonaro is seen as a strongman figure who has rolled back environmental protections and put in peril Indigenous people in the Amazon and across the country.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Bolsonaro repeatedly downplayed the seriousness of the plague, eschewing wearing a mask. Many blame him for rising infections and deaths. Brazil had more than 680,000 deaths from COVID-19, second only to the United States.

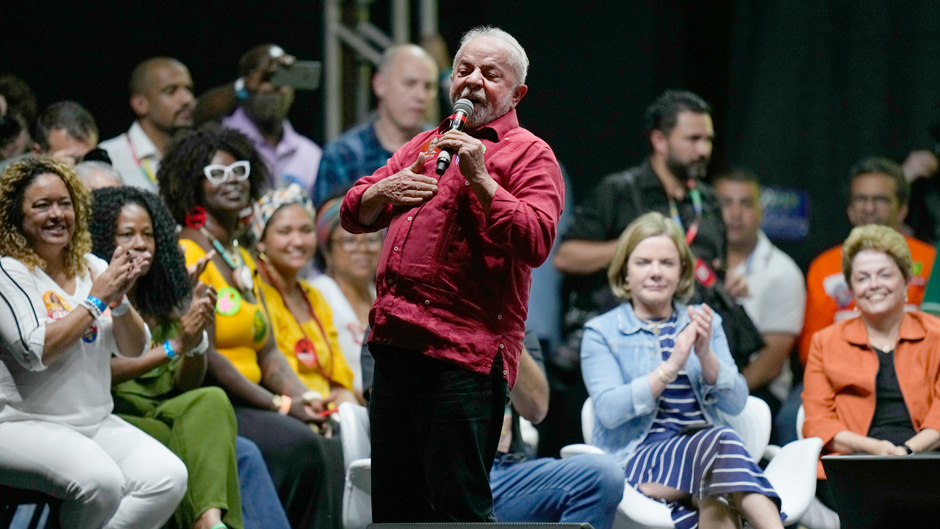

Da Silva, who is leading in the polls, is a member of the Workers’ Party and was president from 2003 to 2010. He enjoyed great popularity during his time in office due in part to a commodity boom that propelled the country into several years of prosperity and social policies that helped many move into the middle class.

Although imprisoned for 580 days on charges of money laundering and corruption, in 2019 the Supreme Federal Court exonerated da Silva from all charges, and he was released from prison.

On Sept. 7—the bicentennial of Brazilian independence—several University professors and graduate students from the Michelle Bowman Underwood Department of Modern Languages and Literatures held a teach-in called “What’s at Stake in Brazil’s Presidential Elections?”

The presenters all agreed that Bolsonaro’s administration has been marked by an increase in the decimation of Indigenous areas and total disregard for Native peoples, a tremendous rise in deforestation of Amazon lands for use as cattle ranches and soybean farms, and a marked persecution of members of the LGBTQ community.

Indigenous peoples in Brazil have been marginalized and discriminated against for decades. It wasn’t until 1988 that more than 300 Indigenous peoples won the constitutional right to be both Brazilian and Indigenous, said Tracy Devine Guzmán, associate professor of Latin American Studies and co-coordinator of Native American and Global Indigenous Studies.

“Before that time, Indigenous peoples shared the status of minors and the mentally disabled,” said Devine Guzmán. Although they have held the constitutional right of differentiated citizenship, including territorial rights, more than three decades ago, their lands have been under constant threat.

“The current administration has promoted an acrimonious political discourse that actually ends up pitting the well-being of Indigenous peoples against that of their compatriots, especially the non-Indigenous poor,” said Devine Guzmán. “This message is divisive. It is dangerous, and it suggests that somehow the occupation of Indigenous lands is a matter of benevolence rather than a constitutional right.”

The state has once again become a perpetrator of violence against Indigenous people, against their lands, and against the advocates who are working on their behalf, according to Devine Guzmán.

Indeed, the Brazilian government has aggressively eroded environmental protections of lands in the Amazon, which has resulted in an “environmental disaster,” according to doctoral student Sam Johnson, a Ph.D. candidate in Literary, Cultural, and Linguistic Studies who presented on the impact of extractionism over the past several years.

Since Bolsonaro took office, the government has allowed and incentivized the continuous expansion of mining and agribusiness in designated, protected Indigenous lands. Many of the forest fires that raged in the Amazon in 2019 were man-made, meant to clear land for mining and other uses, said Johnson. Loss of primary forests in the Amazon region has increased drastically since the current administration took office, he said.

“All these events point to the extractivist agenda of the current government and what is really at risk in the coming election,” Johnson noted.

Brazil is also one of the most dangerous places in the world for women, said Steve Butterman, associate professor and director of the Portuguese program in the Michele Bowman Underwood Department of Modern Languages and Literatures who presented on “Femicide, Impunity, and Misogyny.”

Brazil is the world’s number one perpetrator of assassination of LGBTQ+ people and femicide, according to Butterman. “Violence against women is at an all-time high in the country,” he said.

“Even after the passage of the Femicide Act (a 2015 legislation that recognizes that women were killed because of their gender), Brazil fails to identify and punish gender-based murders,” explained Butterman. According to the Brazilian Forum of Public Security, four girls younger than age 13 are raped every hour in the country, he pointed out.

Every minute in 2021, Brazilian police received an average of one report of intimate partner violence. However, the vast majority of these reports have fallen on deaf ears, he said.

Butterman said that he continues to serve as an expert witness in dozens of asylum cases of members of the LGBTQ Brazilian community. He also aids survivors of severe domestic violence who petition for asylum in the United States because they face prejudices and persecution.

Participants in the teach-in agreed that Brazil’s challenges will not end if a leftist president is elected. But many said they feel hopeful that the existing legislation protecting many marginalized groups will have a better chance of enforcement if Bolsonaro loses.

Gabriel Das Chagas, a doctoral student in Literary, Cultural, and Linguistic Studies, talked about the history of Brazil’s colonialism and institutionalized racism, stating that if daDilva won: “At least we would have a president that believes in and respects the Constitution.”