In 1937, President Franklin D. Roosevelt proclaimed Columbus Day a national holiday to commemorate the adventurer’s historic voyage. Last Friday, President Joseph Biden issued a statement proclaiming Oct. 10, 2022 as Indigenous Peoples’ Day “to honor the sovereignty, resilience, and immense contributions that Native Americans have made to the world.”

From the lens of research and reckoning, a range of University of Miami voices view Monday’s holiday as an opportunity to reimagine the narrative of Christopher Columbus and other historical figures. They strive to pose an accounting that is more accurate and more respectful of the complex histories, lived experiences, and perspectives of those impacted by the legacies of these icons.

Tracy Devine Guzmán, associate professor of Latin American studies in the College of Arts and Sciences and co-coordinator of the Native American and Global Indigenous Studies (NAGIS) working group, emphasized the value of “complicating” these accounts.

“What we need is more nuance in making these kinds of assessments,” said Devine Guzmán. “Without Columbus, we wouldn’t be here having this conversation. So, we want to be able to recognize his historical role while at the same time understanding that those actions led to lasting devastation for a huge part of humanity. We need to acknowledge what people like Columbus did without making it a celebration,” Devine Guzmán added.

NAGIS’ commitment to anti-racism and social justice includes acknowledging and addressing the land theft, genocide, ethnocide, cultural erasure, and diverse sociopolitical challenges that Indigenous populations have faced in the United States and globally.

“We’ve become increasingly aware over the past years of the presence of the past in the way we deal with one another in terms of institutional arrangement—the distribution of resources, power, and land,” said Devine Guzmán. “With regard to Columbus, it’s a good reminder that we can’t erase from our past the complexity of his devastating role on Indigenous peoples in the Americas.”

Devine Guzmán urged the importance of keeping different perspectives in mind. “If we think about Columbus’ voyage in terms of Indigenous peoples, then it shifts our perspective from a kind of celebratory gesture to one of remembrance and a somber recognition of his legacy,” she said.

Caroline LaPorte, an alumna of the School of Law, a descendent of and now a judge with the Little River Band of Ottawa Indians, and a lecturer in the College of Arts and Sciences, highlights the profound legal impact of the Columbus story.

“The notions of the Doctrine of Discovery and manifest destiny are two national falsities that are predicated by the sheer misinformation that this land was somehow ‘discovered’ by any foreign sovereign,” said LaPorte, also director of safe housing at the National Indigenous Women’s Resource Center. “We were here long before Columbus was even a thought. Furthermore, Columbus was never in what was considered the United States of America during the time of his national commemoration. So, we ‘celebrate’ something that did not even occur and in doing so, we ignore the horror of Columbus to the detriment of Indigenous people.”

LaPorte recognized the challenges—feelings of uncomfortableness and the shifting of our beliefs and understandings—posed by embracing our reimagined histories.

“What is hard for many people is this feeling that we have been somewhat caught in our own desire to hold onto tradition, so much so that it becomes part of our identities. And because of this feeling, we have a hard time acknowledging the actual historical truth to what we have become so accustomed to commemorating.

“So, when we as Indigenous people seek to address the offense of commemorating Columbus, it feels like an affront to others' sense of self and belonging, especially within the United States. Feeling that discomfort though is a good indication that some internal work needs to be done and is simply an invitation to confront what might need reorientation within ourselves,” LaPorte emphasized.

Keyra Juliana Espinoza Arroyo, a junior majoring in ecosystem science and policy and minoring in NAGIS, expressed a grim view of the explorer. She grew up between Ecuador and New York and identifies as a member of the African diaspora in Ecuador. Espinoza Arroyo attended elementary school in New York and remembers being taught the traditional hero narrative of Columbus by her teachers.

“It was very triggering because I grew up knowing my history, my creation story, and where my ancestors came from and their struggles,” she said. Yet as an 8- or 9-year-old, she felt “small and invisible” and lacking the voice to counter the misinformation in the story.

“But now I’m 20, and I’ve reclaimed that power to stand up for myself and to speak against what society said was normal,” Espinoza Arroyo said. “And I use my voice to the fullest to educate the truth of my history, my ancestors, my people, and to deconstruct and decolonize Western dominance.”

Education and learning the different prisms and agencies in history are the only way to rewrite the story, Espinosa Arroyo suggested.

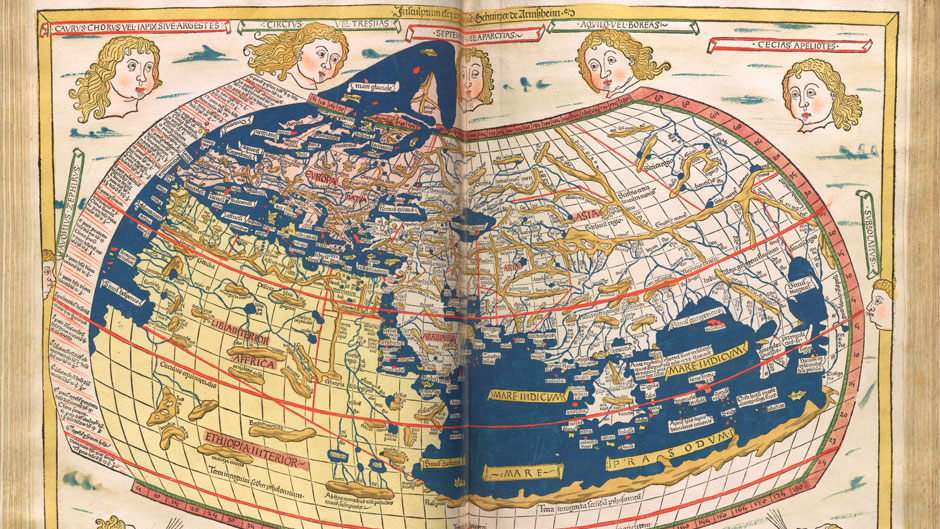

The map Columbus used to chart his journey—the Ptolemy map printed in 1486—is an artifact of the University’s Jay I. Kislak Collection of the Early Americas, Exploration and Navigation.

Kislak curator Arthur Dunkelman noted that the map’s limitation and the explorer’s limited understanding of math doomed the adventurer from the start.

“Why does a man who was lost get so much credit?” Dunkelman asked, noting that “The World as Known by Columbus” map included only Europe and Asia—not North or South America. And based on the information he had, Columbus miscalculated the circumference of the earth by thousands and thousands of miles.

“The heart of the matter in terms of history and politics and control is that no one in Europe believed these [the Indigenous peoples in the Americas] were human beings, so that’s important to remember,” Dunkelman added.

“Columbus was a man of his times who manifested the world view of a European of a certain class,” Dunkelman pointed out. “He had his biases and presumptions—just as most of us have, too.”