Students enrolled in School of Communication associate professor Lindsay Grace’s classes spend a great deal of time playing video games.

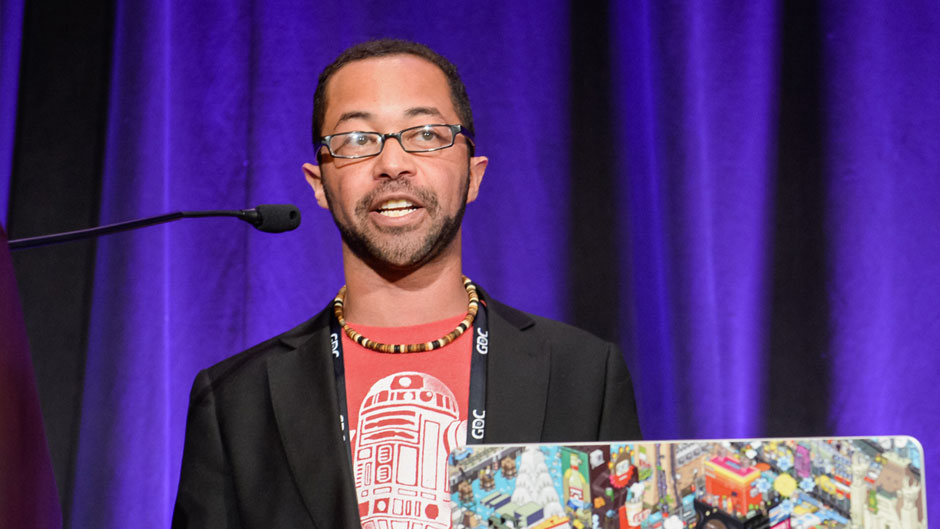

Also the Knight Chair in Interactive Media, Grace is a kind of celebrity in the video game world. He creates games to promote social change, and that is what he teaches in his classes.

Through his work, both at the University of Miami and outside of academia, he strives to create games that will challenge people’s perceptions and biases, as well as entertain them. He has authored more than 70 articles, peer-reviewed publications, and published three books. One, called “Black Game Studies”, was an Amazon bestseller.

“As an academic, Lindsay’s work is diverse and spans between creative practice and traditional game design research. As a practitioner, he focuses on independent games that try to improve the human condition through playful, prosocial, impact-driven experiences,” said Kim Grinfeder, associate professor of interactive media. “It’s always a pleasure to work with Lindsay. His high energy level, enthusiasm, and dedication to the students make him well liked amongst his peers and students.”

Grace is also the director of the Master of Fine Arts in Interactive Media, where he leverages his experience in computer science, new media art, game design, and the humanities to steer the highly interdisciplinary program. “His background makes him uniquely suited for this role,” said Grinfeder.

The love of video games began early for Grace, who was sickly as a child. In one of his many hospitalizations, he was encouraged by nurses to give bloodwork. His reward was 15 minutes playing in the hospital’s arcade. “By the time I was 10, I was programming my own games,” he said.

Now he devotes his time to teaching and developing games that are either educational or persuasive, ones that could change someone’s opinions. “Once you have experienced them, you start to view the world differently,” he said.

“Black Like Me,” for example, is a game he developed to do away with racial stereotypes. Players are offered tiles in different colors, and the goal is to try to match the colors. However, as the game proceeds, the tiles are only different shades of grey and, lastly, only shades of black. By then, the eye cannot differentiate between the shades of black, said Grace. The tiles behave differently, though, and some act out aggressively, and others do not. “Instead of focusing on the color, people have to focus on the tiles’ behaviors,” he said.

Diversity issues in the gaming world are at the core of Grace’s interest. News reports say that the video gaming industry has traditionally been made up of consumers who are male and white. However, Grace said that Black teens are among the majority of players (as of 2015, more than 80 percent of Black teens played games, while only 70 percent of white teens took part in video games).

Although the majority of Black people over the age of 13 identify as gamers, as little as two percent of industry professionals are Black, said Grace.

The associate professor devotes time to many organizations like Games For Change, a group that brings together gaming and immersive media innovators who work on projects that can have a social impact. At a recent conference in Abu Dhabi in the United Arab Emirates, he ran a workshop on creating games for social change.

Besides providing hours of diversion, Grace said that he believes video games can offer many opportunities for behavioral change, empathy, and conflict resolution. One game he created in 2012, “Big Huggin,” substitutes a large teddy bear for a mouse or keyboard and players are confronted with problems and obstacles.

Each time they face an obstacle, they hug the bear instead of shooting someone. “It teaches ways to resolve issues peacefully,” he said.

Another topic that Grace considers to be one of the greatest challenges of the 21st century is misinformation and disinformation.

“For consumers of information, this is an extremely confusing time,” he said. “In the artificial intelligence world, there are a lot of false images and texts and lots of folks trying to misinform. We must equip people with a better radar to determine when something is authentic.”

Toward that end, Grace worked with a team on a game called “Factitious,” where players were presented with news stories, photographs, and articles. They must swipe left or right to determine if the article is true and comes from a credible source.

The game teaches players how to tell fact from fiction, which is also something that Grace is encouraging students to learn in many of his classes.

“We need to teach people visual literacy,” he said. “We need to recognize when the lighting is not right because the algorithms could not figure out the right way to light it. Similarly, you can figure out when a speech (in a video) is fake or not the right person speaking.”

Grace deems that in the age of the internet and artificial intelligence tools such as ChatGPT, which can provide answers to any written request one makes, professors must shape curriculums that help students safely and ethically navigate the virtual world.