“Remembering Jacques Stéphen Alexis—A Centenary Celebration” was part of a series of events around the world over the past year marking the centenary celebration of Alexis’ birth in 1922 and that aimed to impart his ideals of humanism, activism, and patriotism to new generations.

A discussion at the University of Miami Libraries Kislak Center featured his daughter Florence Alexis, an archivist, print and art curator, and included the participation of award-winning Haitian American writer Edwidge Danticat.

Donette Francis, co-director for the Center for Global Black Studies and associate professor of English, moderated the conversation with Alexis’ daughter; Edouard Duval-Carrié, exhibition co-curator and artist; and Béatrice Colastin Skokan, exhibition co-curator and head of Manuscripts and Archives Management at the University Libraries.

In her opening remarks, Danticat read from Alexis’ writing and highlighted his impact on generations of Haitian and Caribbean writers.

“So many think of Alexis’ famous commitment to his country and people through Haitian politics, yet he was also such a beautiful writer,” said Danticat, who collaborated on the translation of Alexis’ third novel, “In the Flicker of an Eyelid.”

She described reading one of his passages about the baking of bread that was so sensory that she lifted the book to her nose to inhale the scent.

“When we are reading Alexis, we always have the feeling that he’s out there waiting to find us, and that speaks to us in the way he was captured and taken from us,” Danticat said.

As a novelist-essayist and political activist, Alexis generated a following for his opposition to the François “Papa Doc” Duvalier regime that came to power in 1957. Alexis was forced into exile in 1959 but returned to Haiti clandestinely in 1961 using false papers. He was captured and brutally murdered. Details of his death remained unknown for four years, kept secret by the dictatorship.

In her presentation, Florence Alexis shared the history of her father’s life through images, quotes, and a voice recording of him speaking at a conference of prominent Black intellectuals.

“From 1961-65 no one knew what happened to my father,” she said. “We heard many versions that were very convenient for Duvalier and others to spread.”

She explained that the family finally learned details of her father’s death when the relatives of one of the guards involved in his capture tried to sell them the arrest record. They refused to buy the document but scanned a copy that listed the simple items in his possession.

Francis described Alexis as “a true renaissance man, one committed to freedom and deeply saturated in the ideals of the era” and said he had lived “a short but purposeful life.”

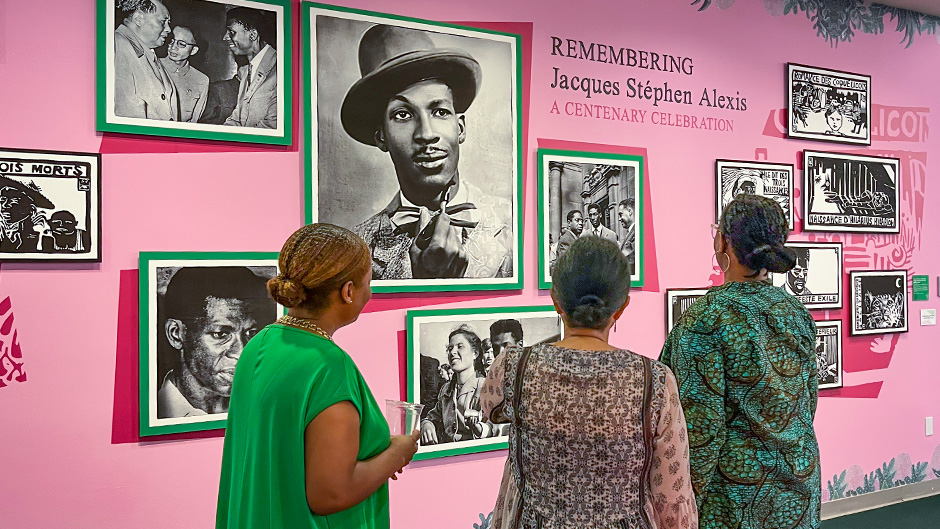

In co-curating the exhibit of art and photographs of Alexis, Skokan explained that she was first and foremost taken by the beauty of his writing and settled on the open public space in the Library Commons because it granted maximum exposure for students.

“There’s lot of traffic there, and we wanted there to be an aesthetic component to draw the students in,” she explained. “We included the contextual information of his life because it’s an opportunity to provide a history and culture of Haiti for undergraduate students.”

When asked what message her father’s writing might convey to Haitians in the diaspora and those living in the tumultuous country today, Florence Alexis responded immediately.

“Unity. It’s a very important word, and that’s why I highlighted that the party he formed—the People's Consensus Party [in English]—was not communist but one that was instead trying to get people of different political persuasions to come together,” she said. “When we see what’s happening today in Haiti, it’s still a good word to repeat and repeat and repeat.”

Florence Alexis acknowledged that thousands of people lost their fathers and members of their families during the decades of brutal repression in Haiti under the dictatorships of Duvalier and his son, referred to as “Baby Doc.”

“The difference is that I have his books, the letters he wrote me, the memory of the courage of my father,” she said. “When you lose someone so young and so promising, you have to find a way to keep that alive.”

Cae Joseph-Massena, assistant professor in the Michele Bowman Underwood Department of Modern Languages and Literatures, and Kate Ramsey, associate professor of history, both in the College of Arts and Sciences, were also praised at the event for their critical support for the initiative to celebrate the Alexis centennial.