In today’s wired world, we all rely on a host of different artificial intelligence tools.

But the newest iteration, called generative AI, can create original text, audio, images, and translate documents—all from a human-directed prompt. It is the latest form of technology shaking up education and other areas.

And it is also clear that these tools will only improve with time. That’s why nearly 80 instructors from a range of disciplines attended the University of Miami’s 9th annual Faculty Showcase on Friday, to explore how to safely use this new technology in their classes. Most participants came with the assertion that they must understand and expose students to generative AI tools to help prepare them for future careers. The event was held at the Lakeside Expo Center and was sponsored by the Platform for Excellence in Teaching and Learning (PETAL).

“Teaching is not something we should be doing in isolation, so how exciting it is to peek our heads into the doors of others’ metaphorical classrooms today,” said Kathi Kern, senior vice provost for education, who leads the PETAL initiative with its director, Miriam Lipsky.

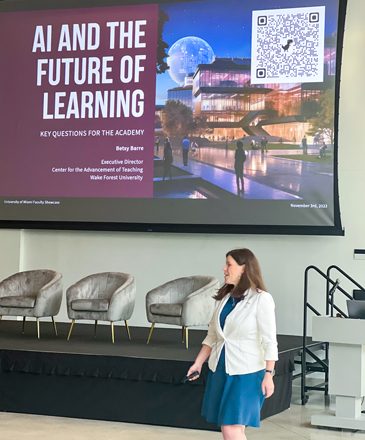

Keynote speaker Betsy Barre, executive director of the Center for the Advancement of Teaching at Wake Forest University, spoke about issues that faculty members should contemplate when integrating AI tools like ChatGPT, BingChat Enterprise, Adobe Firefly, or others into their classes. First, she said educators must consider their desired learning outcomes and then explore how these tools can help students achieve those goals. Yet, Barre cautioned that it is also important that instructors explain to students that generative AI tools can provide biased results.

“I do not think that every course needs to use AI in an intensive way, but there are ways students can use it to accelerate their learning,” Barre said. “For instance, if I’m trying to learn how to swim, having someone else—or AI—do it for you could help by explaining how to swim, or a generative AI tool could watch me swim [via video] and give me feedback, which is helpful for learning, but ultimately, you still need to do it.”

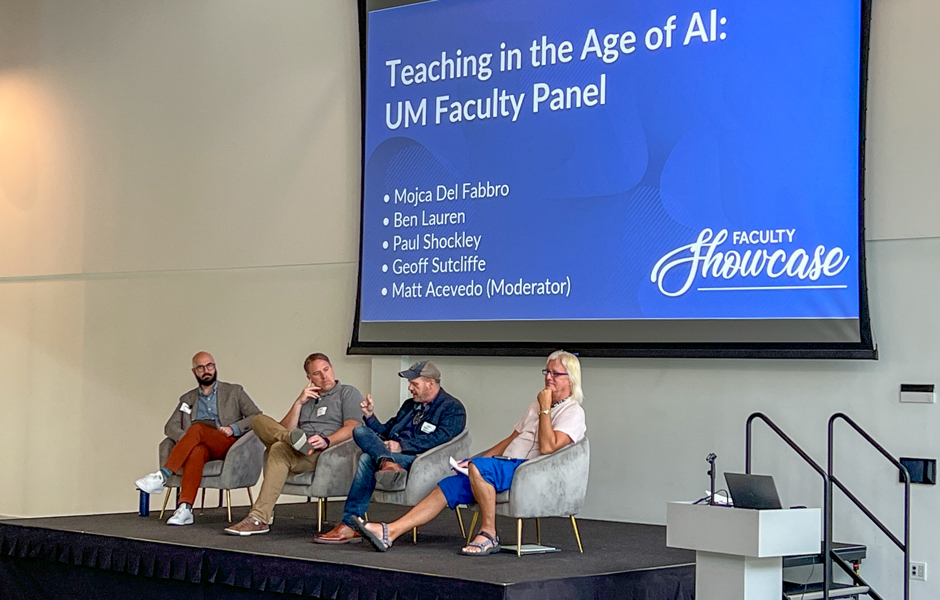

Later in the program, a panel included three University instructors from the College of Arts and Sciences who are using AI in their classes. Associate professor Ben Lauren, who also chairs the Department of Writing Studies, joined religious studies lecturer Paul Shockley and Geoff Sutcliffe, a professor of computer science, onstage for a conversation with Matt Acevedo, executive director of Learning Innovation and Faculty Engagement for the University’s Information Technology division.

Lauren, who teaches writing courses, said he often asks students to use generative AI tools to get feedback on their writing.

“When you are trying to bring new tech into the classroom, anything you are going to ask your students to do, make sure you do it first,” he said. “See what happens. That will go a long way.”

Meanwhile, Shockley asks students to engage in a dialogue with generative AI tools like BingChat Enterprise or ChatGPT by discussing philosophical questions. Then, students must assess the answers for accuracy.

“I’m using AI to build critical thinking skills and to help my students learn how to ask good questions,” Shockley said. “And while, at first, some students were very fearful to use AI, the opportunity to dialogue with such a mind is a structural revolution for students. So, there’s an opportunity for them to grow.”

Although many faculty members who are worried about academic dishonesty have moved away from using generative AI tools, Sutcliffe said that as AI tools are freely available and potentially helpful, it would be a disservice to not expose students—and particularly computer science students—to this emerging technology. He has started asking his students to use generative AI to write computer code, and then improve on that code using the skills they are being taught. He said that typically generative AI-produced code would earn a B or C in his class, and students should be aiming higher.

“It’s unethical to prevent them from using AI because it can improve their education,” he added. “We have to teach students what these tools can do and cannot do, then increase your expectations of the students by allowing them to use such a powerful tool.”

However, Sutcliffe also reminded instructors that new generative AI tools are not perfect. He explained that there are two different kinds of AI—statistical AI, which can get things wrong, such as ChatGPT, and symbolic AI, which can be 100 percent correct. In fact, Sutcliffe said computer scientists will soon routinely use symbolic tools to verify solutions from statistical AI tools, like ChatGPT.

“In the next five years, we must narrow the gap between statistical and symbolic AI,” he said. “As time goes by, it’ll get better. But right now, there’s still room for improvement.”

In smaller learning circles, faculty members also got a chance to see some of the new technology. Hector Noriega, director of student experience at the University’s Information Technology division, showed instructors how to use AI image generator Adobe Firefly to create an image that represents a concept in class and then suggested that they ask their students to write about the process as well. In doing this, Noriega demonstrated how to train students to create very specific prompts that can drastically improve their image results. Educators also can use the tool to enhance their own class presentations with illustrations.

Sarah Cash, a senior lecturer in writing studies, demonstrated how generative AI tools can help elevate an assignment. In Cash’s research writing class, she allowed students to use generative AI tools to develop interview questions and saw that it actually exposed new avenues of inquiry that most students had not considered.

Other innovative instructors, like Kirsten Schwarz, presented ideas on how to harness the power of Blackboard Ultra to make courses more engaging. Schwartz, who teaches in the Department of Teaching and Learning, demonstrated how she uses a Blackboard tool called Kaltura to create video quizzes in her classes to keep students engaged throughout a lesson.

Meanwhile, lecturer John Twichell showed how he partnered with the Lowe Art Museum to use some of their artifacts for object-based learning in his Latin American and Caribbean studies classes.

Lipsky, an adjunct lecturer in the School of Education and Human Development who directs PETAL, said she was revitalized by the event.

“Most days as a faculty member, you go into your classroom and teach, but you don’t see what other colleagues are doing. So, this is an opportunity to share different teaching strategies and get ideas from others,” said Lipsky.

To learn about future PETAL events, including a session on Friday, visit their website.