Between undergraduate and graduate studies in the mid-2000s, Max Fraser took a purposeful detour to write for magazines and periodicals such as Dissent and The Nation, pursuing his interest in the American labor movement and working-class issues.

Yet the labor beat was vanishing, unions were diminished by corporate power, and, besides, Fraser had never envisioned a career in journalism. He returned to academia, earning a Ph.D. as a scholar of American labor, cultural and political history, and began applying his writing skills on a new platform.

Fraser, an assistant professor of history for the University of Miami College of Arts and Sciences, combined his journalistic talents and interest in labor politics in a new book, “Hillbilly Highway: The Transappalachian Migration and the Making of A White Working Class.”

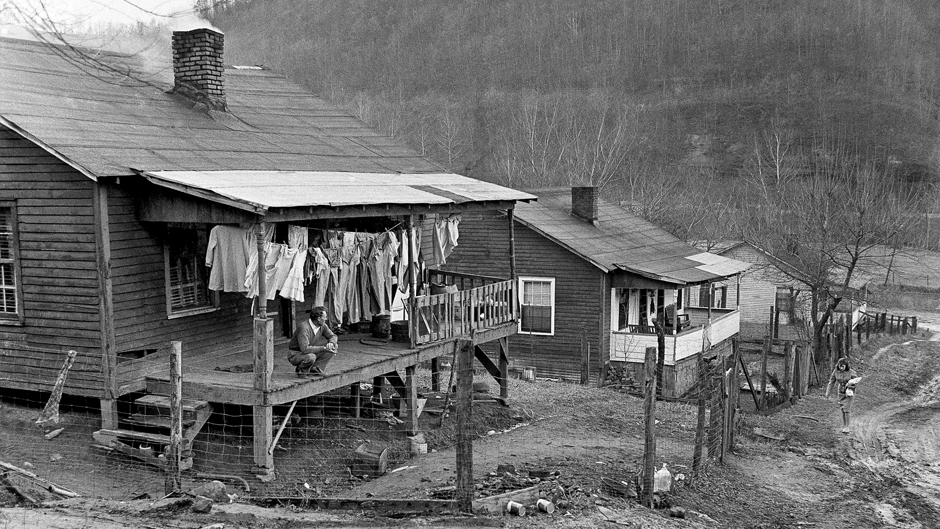

While the “Great Migration”—the migration of six million Black people from the rural South to the urban North from 1916–1970—is relatively well documented, Fraser’s book tells the mostly untold story of the millions of poor, white Southerners who, in flight from the economic crises of places like southern Appalachia, traversed the “Hillbilly Highway” desperately seeking jobs in the Midwest.

“This white working-class population had different ideas and attitudes about the city and their place within it,” Fraser said. “In terms of race and politics, they changed the patchwork of working-class culture in the Midwest in enduring ways.”

This white diaspora “southernized” a lot of these new places in very direct personal ways, Fraser explained, and their presence introduced a new social group alongside the European immigrants—who up until the 1920s had been the primary source of cheap labor for the industrializing United States.

The imprint of labor and activism on economic well-being was instilled early in Fraser, who grew up in New York City. His mother’s father was a union carpenter, and his father was politically active through the civil rights and anti-war years of the 1960s.

“I grew up in a household that, both politically and intellectually, thought about labor and social justice commitments through the lens of labor politics and class issues,” he said. That labor lens has informed his studies, research, and experience to “write about and amplify the narratives of working-class people as much as possible.”

In telling the story of the millions who fled the coal-mining and mill towns of Appalachia, a region that stretches across eight southern states, Fraser dispels a number of myths—misjudgments with consequences that have led to cultural divisions today.

“When they arrive, they’re greeted—and this is a lot of what my book is about—as a kind of ‘foreigner,’ and people point to their supposedly pre-modern mountaineer culture as an indication that they don’t know how to survive in modern urban society,” Fraser pointed out.

Overemphasis on their “hillbillyness” led to a series of misjudgments, according to Fraser.

Restrictive immigration laws in the 1920s had cut off the supply of cheap immigrant workers and northern employers believed that “the desperately poor newcomers would work for whatever pittance they were given, because they were unfamiliar with union politics and the threatening ideas of socialism and anarchism that people have brought from the Old World.”

Employers believed that the hillbilly workers would share a cultural affinity with their bosses; shun identifications with other groups of industrial workers, like Jewish and Catholic immigrants and African Americans; and be docile and exploitable, Fraser explained.

“But that was totally not the case,” he said. “Southern whites joined the union struggles as actively and energetically as their immigrant colleagues in the workplace. Their class identity and class experiences much more powerfully determined their political behavior in that moment.”

Fraser noted that the white Southerners also were mistakenly blamed for inciting the racial conflict that convulsed Detroit and other Midwest cities in the mid-1940s. “These white southern migrants were no more or less racist than other white people were throughout the mid-20th century, but they frequently became convenient scapegoats during such moments of unrest, especially as city officials looked to deflect attention from the deeply embedded forms of structural racism that existed in urban American society throughout this period,” Fraser said.

“The Appalachian migration was a window into this attitude that foretold the kind of divisions of class and culture which have yanked white working-class voters from the Democrats and into the arms of right-wing populists over the last 30 years,” Fraser said.