What makes a criminal? Nature or nurture—or both?

In other words, are we born violent or are we made violent? That question has been debated for centuries. It is the topic of a class called Theories of Deviant Behavior taught by Alex Piquero, professor and chair of the Department of Sociology and Criminology and Arts and Sciences Distinguished Scholar in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Miami.

The answer to the question is not black and white, said Piquero. Many factors affect how individuals behave. Genetics and environment are among some of those factors.

The class looks at traditional theories of the causes of crime and deviance and then reviews more recent perspectives on how social learning, environmental influences, social strains, parenting styles, and even genetic inheritance can influence deviant behavior, said Piquero, who was also appointed by President Joe Biden to serve as director of the Bureau of Justice Statistics, one of 13 federal statistical agencies overseeing the nation’s crime and justice data.

“I want students to remember assumptions we have about human beings and their decision-making patterns; how we measure crime and justice in America, and the challenges and opportunities that exist with informing policy,” he said. “Students I have taught now for over 30 years still write me about my courses as one of the most rewarding facets of their academic career.”

Video: Matthew Rembold/University of Miami

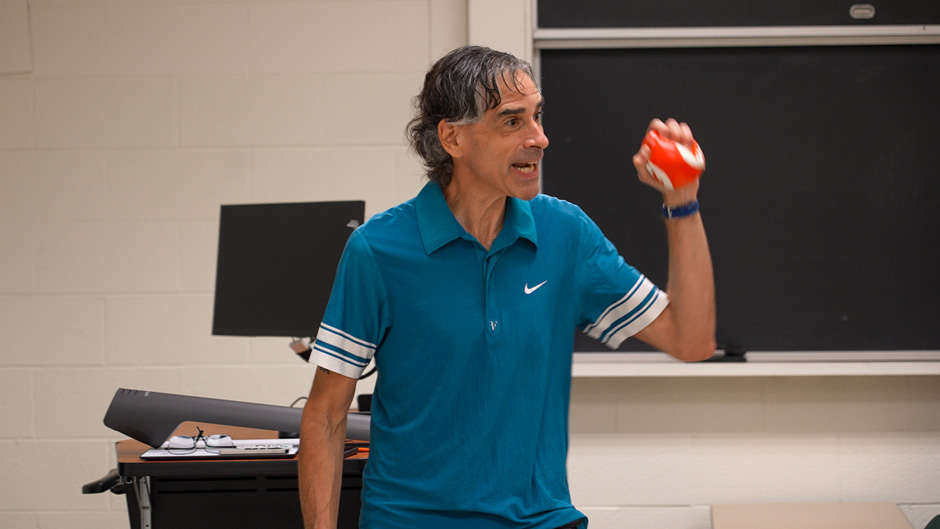

Piquero’s teaching style is memorable. He moves about the room with spurts of energy and throws in unexpected treats to keep the students engaged and alert. He starts and ends class with a music quiz, playing songs to which the students must guess the title, or artists. In a recent class, Bon Jovi and Whitney Houston were among the featured artists.

“I like to play recent songs and oldies,” he said. “My main goal is to create the absolute best experience a student will ever have in a classroom. I do that by making the course fun, engaging, and relevant.”

After Piquero asks students a question, he throws a softball at the student before he hears the answer.

When discussing how neurotransmitters play a role in an individual’s behavior, Piquero brings up dopamine. He suddenly turns and asks a student: does this make you smile? He shows her a Butterfinger candy bar. The girl smiles and then cups her hand as the teacher throws her the small candy bar. He continues to hand out sweets to other students as well.

“Dopamine is what regulates the feeling of happiness,” he said. “Your body wants it and needs it again and again.”

Early studies about criminology focused on family history, said Piquero. But as technologies developed, researchers started looking at the brain and how different hormones and neurotransmitters affect it and a person’s behavior.

Many of the students in the class are heading to careers in law enforcement or law. They see this class as fundamental to their future.

For Greg Turovsky, a senior studying criminology and political science who hopes to go into law, the class has encouraged him to look at people and even television and movie characters from a different lens.

“I think what we are learning in this class is good because in most fields nowadays you are working with people in some capacity,” he said. “It is not just good or bad people. It is important to know human behavior and how people react to things under different circumstances.”

He said he is “loving the class and it is better than I expected. The professor is utterly amazing. He is animated, and he is intelligent and has a lot of experience, and he keeps the class very entertaining.”

For Annika Alves, a junior studying journalism and criminology, the theories that she is learning may help her become a better journalist in the future.

“We are learning the fundamentals of how humans function,” she said. “As a journalist, we are trying to explain every perspective and trying to eliminate as much bias as possible. A huge part of that is ensuring that our audiences be educated beyond the breaking news.”

She feels that in news stories it would be more educational to include more background and context on how the perpetrator came to commit the crime, without humanizing his actions, she said.

“We should try to explain how it got to this point,” she said. “But to explain why it happened and not just showing the facts.”