As a young girl growing up in a family of engineers, Sylvia Daunert didn’t view one of her favorite movies, Fantastic Voyage, as outrageous sci-fi fantasy. Though she never believed shrunken scientists would one day travel through the human body to remove blood clots in the brain, the new director of the Dr. John T. Macdonald Biomedical Nanotechnology Institute at the University of Miami (BioNIUM) saw new possibilities—and her own future—in the 1966 adventure thriller that “explored the unknown universe of the human body.”

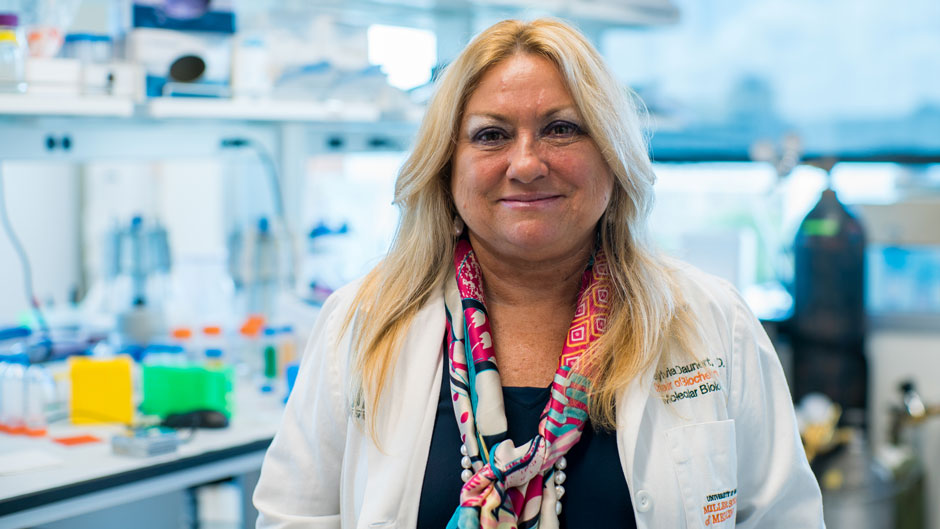

“That always intrigued me,” said Daunert, a pharmacist and medicinal and bioanalytical chemist who has chaired the Miller School of Medicine’s Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology since joining UM in 2010. “When I saw Fantastic Voyage, I thought the day would come when we would cure disease by going directly to the source of the problem.”

Daunert, a pioneer in designing infinitesimal diagnostic tools and biosensors by genetically modifying proteins and cells, is committed to elevating BioNIUM to national and international prominence. She plans to do so by doing what she has done her entire career: fostering biomedical, environmental, and pharmaceutical breakthroughs on a nanoscale by collaborating on a megascale.

“Sylvia is one of our most accomplished faculty scientists who, in addition to her many discoveries and patents, is a team builder who has literally broken down the walls in her department’s laboratories,” said Jeffrey L. Duerk, executive vice president for academic affairs and provost. “We welcome her vision for expanding BioNIUM’s University-wide mission by cementing its links to the Miller School’s strategic plan and breaking down any perceived walls across the university. BioNIUM and Sylvia are both ideal manifestations of the University’s interdisciplinary team science initiatives and aspirations.”

Opened in 2015 with a $7.5 million grant from the Dr. John T. Macdonald Foundation and matching support from the deans of the Miller School, the College of Arts and Sciences, and the College of Engineering, BioNIUM is on the fourth floor of the bustling Converge Miami, formerly known as the Life Science and Technology Park, east of the medical campus. In addition to administrative offices and laboratories, it includes 2,500 square feet of state-of-the-art “clean rooms” that provide the particle-free environment essential to designing and fabricating nanoscale devices, which, with features at one millionth of one millimeter in size, can be contaminated by a speck of dust.

It is where Daunert, who holds the Lucille P. Markey Chair in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, and her research group can refine the mind-boggling array of nanotechnologies they are developing in collaboration with other UM scientists and physician-scientists. Among their innovations: microneedles that deliver medicine to the inner ear before dissolving, sensors that detect drowsiness in drivers, biomarkers that detect and help manage inflammatory bowel disease, and, yes, submarine-like “nanocarriers” that deliver stem cells or drugs exactly where they need to go to make repairs—a la Raquel Welch and the other miniaturized actors who traveled to the brain in Fantastic Voyage.

Building on the success of her predecessor, Dr. Richard Cote, the founding director of BioNIUM and past chair of the Department of Pathology, Daunert already has begun expanding BioNIUM’s University-wide mission by tapping two new associate directors, a post she previously held alone. They are Ashutosh Agarwal, assistant professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering in the College of Engineering and Marc R. Knecht, associate professor in the College of Arts and Sciences’ Department of Chemistry. Sung-Jin Kim, director of the Nanofabrication Facility and associate professor in the Department of Electrical Engineering, will continue providing leadership to BioNIUM in micro- and nanofabrication. To expand BioNIUM’s educational mission within UM and the community, Sapna Deo, professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, will serve as the director of training and education.

“Sylvia is ideal for this job because she’s not just a scientist who can do all these things. She is also a personality who you like to work with,” Agarwal said. “You need both things—the scientific expertise, which a lot of people have—and the ability to forge diverse collaborations. That’s essentially the mission of BioNIUM: to be the backbone for interdisciplinary collaborations in the bio-nano space.’’

Born in Spain, Daunert grew up in Barcelona where she earned a doctorate in pharmacy and later a Ph.D. in bioanalytical chemistry from the University of Barcelona. Coming from a long line of engineers, she broke a tradition that spans five generations by becoming the only scientist in her family.

“I am the black sheep of the family,” Daunert joked, noting that, even as a little girl, she wanted to unleash the power of nature. “When I played with dolls I would take leaves and flowers and grind them to make magic potions and perfumes. I was always mixing up ‘cures’ for my dolls.’’

The holder of 40-something patents, she was first introduced to nanotechnology while a Fulbright Scholar at the University of Michigan, where she earned her M.S. in medicinal chemistry and met her husband, Leonidas G. Bachas, now the dean of UM’s College of Arts and Sciences.

“At the time, I was designing anti-viral and anti-cancer drugs, but I thought synthetic drugs were not always the answer,” Daunert recalled. “I thought the answer was at the molecular level, that it would be better to modify the body or intervene genetically to cure disease. Throwing foreign substances indiscriminately, without targeting the right place in the body, can cause so many negative side effects that it could not be the answer. Or, if it is, then you have to do it in a way that the drugs go only where they need to go.”

The right location, the right time, and the right dose. Now the basis for targeted drug delivery, part of what’s become known as precision medicine, that principle would guide Daunert’s basic science research and move her research group’s inventions and discoveries beyond the laboratory, to publication in more than 250 journal articles, and to real-world applications—a world where she was often the only woman.

In 1990, after joining the faculty of the University of Kentucky, where she worked in the Department of Chemistry and in the Department of Pharmaceutical Sciences, she would prove her research prowess by winning four major grants during her first year as an assistant professor and earning tenure in a record three and a half years. For her contributions to the well-being of the commonwealth, she was tapped into the Honorable Order of Kentucky Colonels, just one of numerous awards she has received around the world.

The Kingdom of Spain honored her with her homeland’s highest civilian title, Excelentísima Sra. (Señora) Doctora. She is also the first woman appointed an Honor Academy Member of Spain’s Reial Acadèmia de Farmàcia de Catalunya and was inducted into the world’s oldest academy, the Real Academia Nacional de Farmacia, founded in 1589.

More recently and closer to home, Daunert and her clinical collaborators were recognized for developing an on-the-spot test that diagnoses the human papillomavirus, and wristbands and sensors that record the carcinogens firefighters are exposed to on the job—an innovation that prompted the Florida Legislature to require all fire stations be equipped with filters that remove cancer-causing compounds.

Asked how she manages to explore remedies for so many diverse diseases and hazards, Daunert jokes that she has “scientific ADHD”—Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. But that’s only because she is, first and foremost, a problem-solver and, as an avid collaborator, is often called upon to seek solutions for clinicians who need better ways to help their patients or advance the well-being of society.

Now, she, Argawal, Knecht, Kim, and Deo look forward to marshalling BioNIUM’s 32 faculty members, who belong to 12 disciplines and have cumulatively secured more than $94 million in research funding, into a bio-nano powerhouse that will attract national center and project grants that take advantage of their collective expertise.

“You’ll never advance science if you focus on one area,” Daunert said. “The key to being successful is to collaborate with people who have the expertise in areas that you do not have. You can’t have a big ego. You have to be humble enough to recognize what other people know that you don’t know and learn from them.”