Farmers will be hit especially hard, with higher temperatures, drought, and flooding affecting both the quality and quantity of their crops. Wildfires will burn as much as six times more forest area every year in parts of the U.S. By 2090, an additional 2,000 premature deaths will occur annually due to extreme heat.

But that’s just part of the bad news. Other disturbing numbers and alarming projections of how a rapidly changing climate will affect the U.S. paint an even bleaker picture: an increase in skin and eye infections caused by more droughts; a spike in the frequency and severity of allergic illnesses such as asthma and hay fever; warmer temperatures giving rise to more cases of vector-borne diseases like dengue fever, chikungunya, and Zika; 570 million lost labor hours; a 10 percent drop in GDP.

Such are the dystopian-like projections cast for the nation in the long-awaited Fourth National Climate Assessment. Issued by the federal government the day after Thanksgiving, when many people were distracted, the report presents the gravest warnings yet of the impacts of climate change on the U.S.

“Climate change creates new risks and exacerbates existing vulnerabilities in communities across the United States, presenting growing challenges to human health and safety, quality of life, and the rate of economic growth,” reads the report, authored by scientists from 13 federal departments and agencies.

More than 1,600 pages long, the comprehensive report is mandated by Congress and warns that climate change is not only already impacting the U.S., but that the effects are getting worse. It warns that while actions to mitigate and reduce the effects of a changing climate have “expanded substantially in the last four years,” they do not yet approach the scale considered necessary to avoid significant damages to the economy, environment, and human health in the coming decades.

“The biggest innovation in this synthesis report is that there is a serious effort to address the economic impacts of inaction with respect to climate change,” said Ben Kirtman, a professor of atmospheric sciences at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science. “The report estimates a 10 percent drop in U.S. GDP if we do not stabilize the climate. This is remarkable and quite daunting.”

South Florida is already experiencing the effects of climate change. Kirtman, who is also director of the NOAA Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies (CIMAS), noted that over the past five to seven years, the region has seen an increase in the number of “clear-sky flooding days” along with a spike in nighttime temperatures.

“This increase in the nighttime lows increases energy demands—more air-conditioner use—which increases CO2 emissions,” he said, adding that more nighttime lows has resulted in a “disproportionate affect on the quality of life in sectors of society that have less access to air-conditioning.”

It is the risk of compound flooding—extreme rainfall events combined with sea level rise and even storm surge—that South Florida should be particularly concerned about, Kirtman said. That risk, he warned, is projected to continue to increase. “We also need to be mindful of how ocean warming and ocean acidification are negatively impacting our coastal ecosystems,” he said. “The health of the Florida reef track is already seriously challenged by the changes in ocean temperatures and acidity. If we continue on the current path, the damages may be irreversible.”

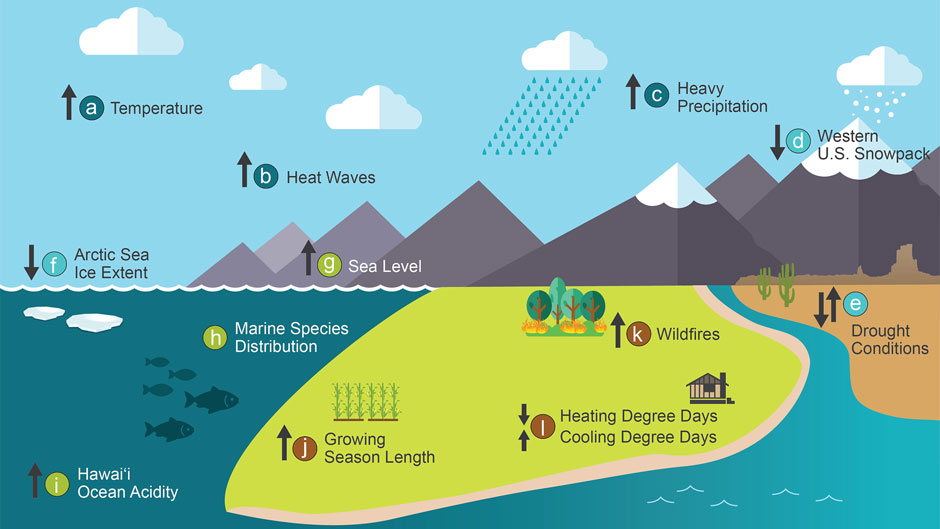

Indicators of climate change: Observations from around the world show the widespread effects of increasing greenhouse gas concentrations on Earth’s climate. High temperature extremes and heavy precipitation events are increasing. Glaciers and snow cover are shrinking, and sea ice is retreating. Seas are warming, rising, and becoming more acidic, and marine species are moving to new locations toward cooler waters. Flooding is becoming more frequent along the U.S. coastline. Growing seasons are lengthening, and wildfires are increasing. These and many other changes are clear signs of a warming world.

The report, which breaks down the potential impacts by U.S. region, also said climate change will increase the frequency and severity of red tides, toxic algal blooms that deplete oxygen in the water and kill marine life.

“While the Florida red tide organism Karenia brevisoccurs naturally in the Gulf of Mexico, the data show that excess nutrients generated by various human activities in Florida have increased the intensity of these toxic blooms about fifteen-fold,” said Larry Brand, a phytoplankton ecologist at the Rosenstiel School. “To the extent that climate change increases rainfall in Florida, it will lead to an increase in nutrient runoff from land into the coastal waters and an increase in the red tide.”

Residents of Southwest Florida are all too familiar with the algae that cause red tide. For the past year it has devastated their coast, killing marine life, triggering respiratory distress in humans, and hurting tourism and local businesses.

More actions to mitigate the impact of our changing climate are needed, said Joanna Lombard, a professor in UM’s School of Architecture who is part of a U-LINK (University of Miami Laboratory for Integrative Knowledge) team project examining climate adaptation.

“When we think about rising heat and sea levels and more intense storms, there are two primary strategies,” Lombard explained. “The first action needed is to bring our carbon emissions to a halt and work toward carbon sequestration. This begins to turn off the engine that is driving these effects. The importance of this can’t be overstated and commitment to these goals in the building industry transforms where we build, how we build, the way that we power our buildings, and the materials and resources we use, or more significantly, conserve.”

Indeed, a global reduction in CO2 emissions would help mitigate the effects of climate change, the report states. But in the absence of such a strategy, “it is possible to reduce these damages through adaptations,” said David L. Kelly, a professor of economics in the University of Miami Business School whose research interests are in environmental economics and policy.

“Coastal infrastructure can be fortified. Things like improved pumping stations help reduce flooding. Steps can be taken to minimize the spread of viruses such as West Nile. Some agriculture can be moved indoors. The report includes estimates as to how much damage can be reduced through adaptation. The report shows that most of the coastal property damage can be reduced through adaptation, for example. However, it is not easy for outdoor workers to adapt, and the report assumes no adaptation is possible when computing the labor damages.”

Lombard echoed Kelly’s sentiments, saying we must adapt our way of life to changing environmental conditions. “This means that in Miami-Dade, we acknowledge the porous limestone sponge beneath us and that sea level in our part of the world is not simply a coastal condition but rather also pushes upward from below our communities,” she said. “We have some immediate possibilities to adapt to the current state. For example, we can fully invest in and expand our park system’s greenways and blueways, literally green our community—more tree canopy, more planting, more parks and open spaces, more naturalized areas to detain and filter storm waters.”

Education and outreach, much like the efforts being undertaken by CIMAS, can help inform the public and scientific communities about the impact of climate change, said Kirtman.

“CIMAS focuses on much of the basic research and data collection that provides the underpinning of our understanding of how the climate system works and informs our ability to model its future,” Kirtman said. “CIMAS scientists at all levels regularly engage K-12 students through open houses and class visits in the basic science of the ocean and atmosphere. And CIMAS scientists often participate in public to discuss the impacts of the changes we have currently observed and the projections of the future.”