When the morning lights come on, the seduction begins. After spending the night side by side but in separate compartments, male and female zebrafish finally mingle and waste no time getting down to business.

In a frenzied dance, the torpedo-shaped males chase the fat-bellied females until they release a shower of tiny, translucent eggs into the water. Immediately fertilized by an invisible spray of sperm from the males, the eggs drift downward, falling through a grate in the small breeding tank. Within minutes, hundreds of embryos collect on the bottom, a precious bounty owed largely to Ricardo Cepeda, a former literature teacher in Colombia who can conjure the zebrafish’s amorous antics on demand.

“They’re the same as us,” he said of the striped vertebrates that share 70 percent of human genes. “They want chocolate, flowers, music, and a penthouse suite.”

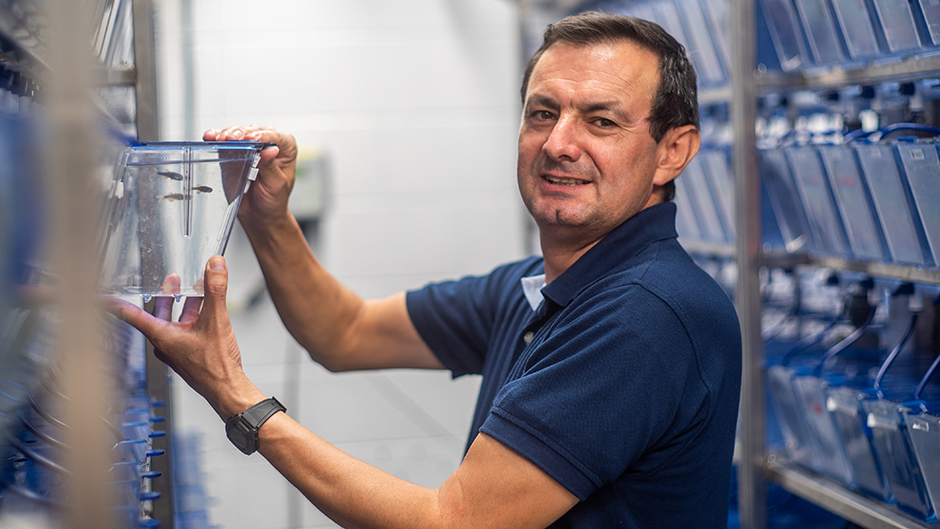

The manager of the University of Miami Zebrafish Facility, Cepeda is so good at keeping nearly 4,000 zebrafish happy, healthy, and reproducing that he rarely says no to the stream of requests from researchers across the University who use the popular aquarium fish to model human genetics and disease. Usually, he promises the embryos will be ready shortly after 9 a.m., when the lights come on, and the fish that were separated in a breeding tank overnight are finally allowed to mix. But if you need them at noon, or 2 p.m., or midnight, no problem.

The fish whisperer can make it happen.

“He’s amazing,” said associate professor of biology Julia Dallman, the director of the facility who started the Department of Biology’s zebrafish colony with 40 “pioneers” she brought from New York after joining UM in 2007.

“The thing that speaks loudest about Ricardo’s relationship with the fish, and how much we depend on him, is when he goes away the fish stop laying eggs. They go on strike,” Dallman said.

Aside from their similar genetic structure, zebrafish are valuable research models because they are nearly transparent during their first week of life and develop at warp speed. In their first hour, they grow from one cell to four; in two hours, they have 64 cells. As such, researchers who can literally watch their heart, brain, lungs, blood vessels, digestive system, eyes, and ears develop, can modify their genes to replicate a number of mutations linked to inherited disorders.

So it’s a serious setback when the normally prolific and promiscuous zebrafish go on strike. Research screeches to a halt, and valuable time is lost. That has happened elsewhere, but not at UM, because after a decade of paying close attention to how zebrafish behave, Cepeda can read them like one of the literature books he used to teach.

Their equivalent of chocolate is a tempting buffet of tiny brine shrimp and dry larva cereal that student helpers Evan Sarmiento and Hannah Hiraki squirt into the tanks by eye-dropper twice a day. Their music and flowers are provided by the meticulously controlled temperature, pH, and salinity of the water, which is filtered and monitored via a complex and redundant system of tanks and sensors.

And the penthouse suite? That’s the small breeding tanks Cepeda leaves on the counter overnight with the male and female zebrafish he’s carefully selected the afternoon before to fulfill his research requests. Soon after his morning arrival, he replaces the water in each tank—washing away any waste left overnight and re-oxygenating the water before the mingling begins.

“It’s like a five-star hotel,” he said. “Don’t you expect clean sheets and a refreshing shower every morning?”

When Cepeda left the violence of his Colombian homeland 20 years ago, he certainly had no expectation of becoming a research associate at UM. He taught Spanish for a while, bussed tables, and cleaned pools, a job that bored him but taught him enough about water quality to land him part-time work taking care of some cranky research frogs for a cell biologist at UM’s Miller School of Medicine.

Within a few months, Cepeda had the celibate frogs breeding again, and when Dallman, who uses zebrafish to study neurological disorders, joined UM, she turned to Cepeda for temporary help setting up the Department of Biology’s zebrafish facility in the basement of the Cox Science Building.

Ten years later, the largest zebrafish facility in Florida is home to about 50 different lines of zebrafish that, reproducing like clockwork, are used to study everything from autism disorders and hearing loss to heart function and nerve regeneration.

Cepeda’s simple secret: “I just watch and learn,” he said.