Dorian’s destruction was slow and torturous, as the Category 5 storm virtually came to a standstill over the Bahamas for more than a day, leaving dozens dead and destroying thousands of homes.

With sustained winds of 185 mph, Dorian was the strongest hurricane on record to strike the Bahamas.

Weeks later, another cyclone, Lorenzo, would make headlines of its own, becoming the easternmost Category 5 Atlantic hurricane on record when it raced toward Ireland and the United Kingdom.

Two Category 5 storms in one season.

That’s only the second time in 12 years that has happened.

But as rare as the occurrence of two super storms in one season is, it wasn’t the only oddity that will make the 2019 Atlantic hurricane season unforgettable.

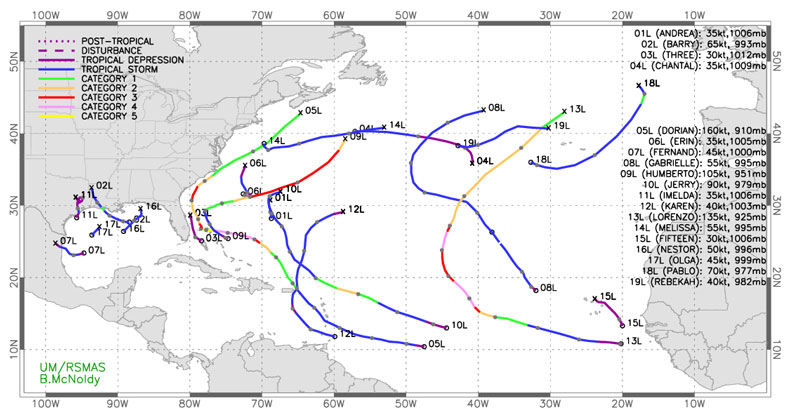

The Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea experienced hardly any storm activity at all.

“Within all of that area combined, there were just two Category 1 hurricanes for under six hours combined—Barry, just as it made landfall in Louisiana, and Dorian, just as it made landfall in the Virgin Islands,” said Brian McNoldy, a senior research associate and tropical cyclone expert at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science. “A total of seven tropical storms passed through those two areas, but also only briefly. Most of the activity this year was in the subtropics.”

For the fifth consecutive year, the season got off to an early start, when Subtropical Storm Andrea formed in the Atlantic near Bermuda a week and a half before the official start of the season.

That system quickly fizzled out, its relatively short lifespan becoming indicative of a number of weak and short-lived storms this season. In fact, of the 17 named storms that have developed this season, seven lasted for only a day or less.

“There have been 62.75 named storm days so far,” said McNoldy, “and Dorian and Lorenzo alone account for 37 percent of that total.”

But brevity doesn’t tell the whole story. “While Imelda was barely a named tropical storm for just six hours, it caused several billion dollars of damage in eastern Texas,” said McNoldy.

Indeed, the ninth named storm of the 2019 Atlantic hurricane season, Imelda dumped as much as 43 inches of water in some parts of southeast Texas, damaging hundreds of homes as one of the wettest tropical cyclones in U.S. history.

At least one characteristic held true this year, as September lived up to its reputation as the peak of hurricane season. Three tropical storms—Fernand, Gabrielle and Imelda—along with Hurricanes Humberto, Jerry, Karen and Lorenzo all formed in September.

All’s now quiet in the tropics, and with just three weeks remaining in the season, it is expected to stay that way.

“But November can and has produced some very notable storms with now-retired names,” said McNoldy, referring to the fact that when hurricanes are particularly destructive, their names are removed from the list of predetermined storm names. “In fact, five names have been retired due to November hurricanes—as many as June and July combined.”

The five: Otto in 2016, Paloma in 2008, Noel in 2007, Michelle in 2001 and Lenny in 1999.

“None of those affected the U.S., though,” said McNoldy, who publishes his own blog, Tropical Atlantic Update, and has been the tropical weather expert for The Washington Post’s Capital Weather Gang since 2012. “The strongest U.S. land-falling November hurricane was Kate in 1985, which hit near Panama City, Florida, as a Category 2 hurricane on Nov. 21.”

McNoldy weighs in on three other important questions about the 2019 Atlantic hurricane season, which ends Nov. 30.

How does the 2019 Atlantic hurricane season stack up in terms of activity?

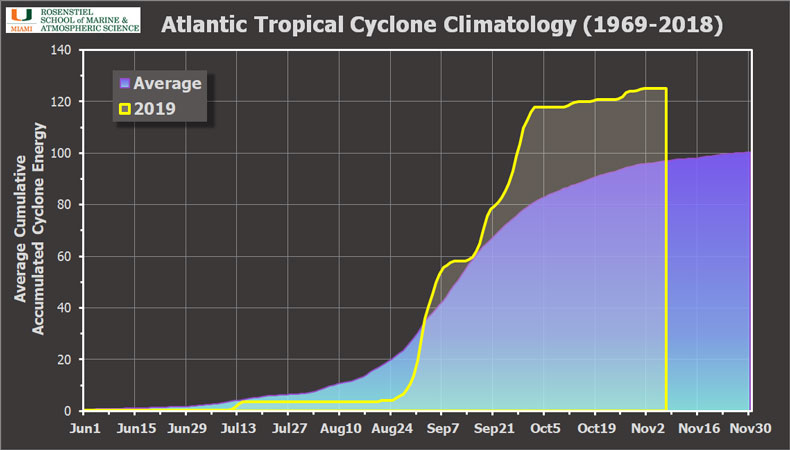

As of today, the 2019 Atlantic hurricane season has had 17 named storms. Six of those became hurricanes and three of those became major hurricanes (Category 3+). The average values for an entire season are 12.1, 6.4 and 2.7. Another popular metric for gauging the overall activity is the Accumulated Cyclone Energy, or ACE. This quantity is essentially the sum of the squares of the six-hourly peak wind speed of every storm. In terms of ACE, the season is at about 124 percent of average for the date. While the season will end up slightly above average, it is not wildly out of the ordinary.

What could account for the dearth of storm activity this season in the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea?

Over the Aug. 15 through Oct. 15 period—my arbitrarily chosen heart of the season—the Gulf and western Caribbean water temperatures were slightly warmer than average, while the eastern Caribbean was near average. So that doesn't help explain it. However, something that does show up in both regions even in that two-month average is that the low-to-mid levels of the atmosphere were drier than normal (lower relative humidity). Additionally, the entire Caribbean as well as the western Gulf had significantly higher vertical wind shear compared to average, as did much of the deep tropics. Those two factors could easily explain why the Gulf and Caribbean were so quiet and why there was not even much activity in the tropics in general. The vertical wind shear anomalies dropped off north of 20°N or so across the basin.

Can climate change be playing a role in the odd storm events we’ve been seeing?

It’s always risky to assign climate change to what we see in any given season. If storms like Dorian and Lorenzo are linked to climate change, what about Erin and Fernand? This season had an abnormally large percentage of weak and short-lived storms, and virtually no activity in the Caribbean or Gulf. If those attributes become more common with climate change, it would make a lot of people happy. Signals associated with climate change may show up in long-term statistics and trends, but we should be careful when looking within a season or even season-to-season.

A timeline of the average seasonal ACE (Accumulated Cyclone Energy), using the past 50 years as a climatology with 2019’s values overlaid in the yellow line. Created by Brian McNoldy.