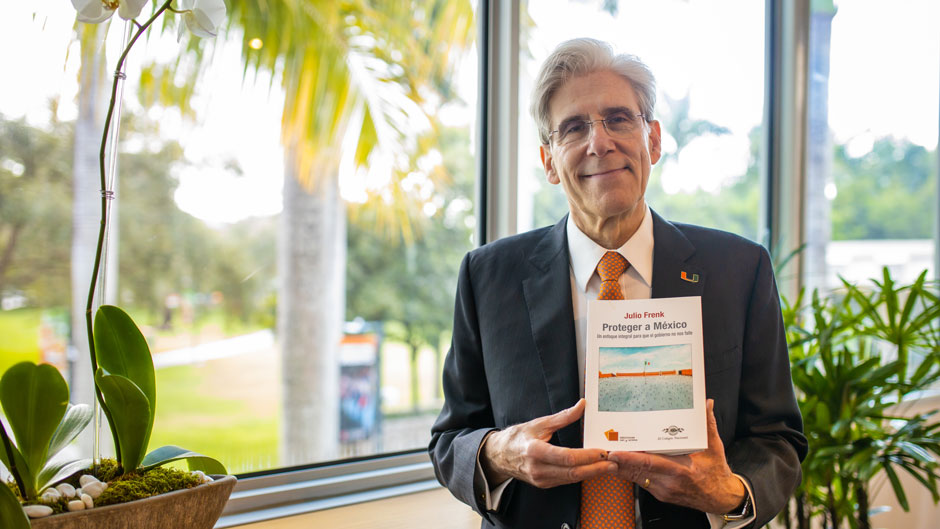

Proteger a Mexico: un enfoque integral para que el gobierno no nos falle, published in Spanish and introduced in November at the Guadalajara International Book Fair, delivers a diagnostic of the development and impact of the landmark Mexican government health care initiative launched in 2004 that provided care to tens of millions of Mexicans, most of them peasants and farmers.

University of Miami President Julio Frenk, the former health minister of Mexico from 2000 to 2006, was the driving force behind strategizing and coordinating passage of the popular initiative.

In the book’s broader and more personal argument, Frenk writes that his deep concern—“I’m worried for Mexico” he notes in his opening line—owes to the rise in Mexico and around the world of populist rhetoric that eschews accountability and instead blames “the other”—political opponents, migrants, ethnic or religious groups, or other societal scapegoats—for any range of problems that occur.

“I don’t think anyone imagined five years ago that we would see the return of the rhetoric and practices of the 1930s and '40s,” he said in a recent interview, referring to the abuses and atrocities that led to World War II.

“After all the optimism that followed the Allied victory, the construction of a very prosperous society, the extension of democratic practices, the fall of the Berlin Wall, the dissolution of the Soviet Union, I certainly didn’t think as someone born in the first decade after the war, that we would see a return to that. And yet we are seeing it.”

Frenk cites the “three Cs”—crime, corruption, and corporatism—that plague Mexico and other countries, “eroding its social fabric,” and perpetuating inequalities. In Proteger, he tackles corporatism, which claims privilege for certain groups in society—and excludes others—as the most pernicious. Despite Mexico’s “long transition” to democracy launched with the student uprisings in 1968, which eventually led to the historic 2000 election that ended 72 years of single-party rule, Frenk says that the institution of health care had remained “a bastion of corporatism.” Regardless of need or even status, prior to enactment of Seguro Popular, only one question dictated access to care: Who is your employer?

Motivation to write

The centerpiece of Proteger is a case study on Mexico’s health care system. Frenk bookends this “conceptional core” with an opening reflection on his personal biography and a closing call for unity that can be expanded to other countries.

He begins with the “why” for the book: When Frenk’s grandparents immigrated to Mexico in the 1930s, fleeing persecution and poverty from a disintegrating Germany, they were welcomed “with open arms” as strangers in a strange land despite cultural and linguistic differences.

“My motivation is very simple. The German government failed my ancestors in the 1930s. Not only did the government not protect them, but the government itself then became the main perpetrator of the violation of their rights. It was the generosity of strangers that saved my grandparents’ and my father’s lives and made my life possible. Mexico is the country that did that—and I owe a debt of gratitude.”

In the epilogue, Frenk reemphasizes the concept of generosity, advocating national unity based on universal care for all, and espousing his hopes for a future where his two daughters and their generation (the book is dedicated to Sofia and Mariana) are protected in a Mexico free from the dangers of populism and the restrictions of corporatism.

Defining protection

Frenk advances the premise that a government’s fundamental responsibility is to protect its citizens on three levels: individual, from attacks and violence against person or property; community, providing economic opportunity, clean air, safe food and drinking water; and national, protecting borders and sovereignty—which extends to planetary safeguards, such as protecting the planet from climate change.

He warns readers not to confuse this fundamental duty with two “distortions” that governments sometimes advance: “protectionism,” the use of trade and tariffs to shield domestic industries, or the corporatist demagoguery populist leaders use to aggrandize themselves.

“I’m talking about protection against the real risks that citizens face,” he said. “Not the fear mongering and inventing of imaginary enemies so that then the leaders of the government can proclaim themselves the ‘protectors of the nation,’” he explained.

Experience and expertise

For the essay core, Frenk draws on his decades of experience as a public health specialist and, in a recent interview, discussed his role bringing Seguro Popular to life in the early 2000s.

“Health care is a right. It’s not a merchandise like a car that you buy, and it’s not a privilege,” he said, explaining that in corporatist thought your occupational position mediates the way you exercise that right.

“The reforms that I led when I was minister of health were meant to break that,” Frenk added.

Half of Mexico’s 100 million people at the time lacked access to health care. Fifty million non-salaried workers and their families, mostly poor peasants but also lawyers, doctors, and other professionals lacked care because they had no employer. Frenk set up a multidisciplinary task force that spent nearly two years studying the problem.

To counter the barrage of criticism—you’re too idealist, you’re dreaming, these people are barely literate and don’t understand insurance—he responded from his training as a social scientist. Let’s do a pilot, try it on a small scale, then conduct an independent assessment.

The pilot in five Mexican states proved to be a success. “It turns out that poor people have a very good sense of what it is to not drive yourself even deeper into poverty because you have to pay out of pocket for health care,” he said.

Frenk took advantage of his non-partisan status to earn trust with all five of the political parties at the time. “I knew I had a political job—I wasn’t naïve, but my mantra is that I am a health professional in a political job, not a politician in a health job.”

He conducted hundreds of meetings with leaders in the Mexican congress to build consensus, met repeatedly with the secretary of the treasury and president to earn support.

“I told my staff: If any of the people who are eventually going to vote on the legislation wants to talk with me, I am available,” he said.

Build a legacy

In Proteger, Frenk urges the current Mexican administration to build on the progress made during the past 15-plus years with Seguro Popular. He hopes President Andrés Manuel López Obrador will anchor his own legacy by working to remedy the imperfections that have surfaced and avoid making an “irreparable mistake.”

He uses the closing section to contemplate the natural inclination to build a legacy and leave something of value behind. To do so, Frenk says, leaders must meet two requirements: avoid making an irreparable mistake—usually having to do with inappropriate behavior, such as sexual misconduct or committing an act of corruption, and thinking that they are above the law—or believing that “everything before me was wrong and that I’m here and will be remembered as the person who fixed all the mess I inherited.”

He describes López Obrador as a “righteous man” and does not believe he will succumb to the first flaw but is worried by other signs of the second.

“What I’m describing here in Mexico is the erosion of democracy, institutions being dismantled,” he said. “It’s an erosion that could take time, a story that’s unfolding.”

Embracing diversity

Proteger a Mexico, or Protecting Mexico advances Frenk’s belief that diversity creates richness, a credo that he has seeded in a range of initiatives and dimensions as University of Miami president since 2015.

“Each of us is all of us, there’s no pure anything,” he said. “We need to understand that the history of the human species is the history of mobility and intermarriage, and that this notion of purity has led to the worst atrocities.

“We need to embrace that we are multidimensional—and that’s a richness that we carry diversity within each of us. That then will allow us to be much more empathetic and to embrace our own diversity.”