The odd-looking devices made 7-year-old Noel Ziebarth a bit nervous. They looked like something right out of a science-fiction comic book, had peculiar names like phoropter, retinoscope, and tonometer, and would be used, she learned, to examine and peer into her eyes.

Sitting next to her was an eye specialist, who explained how each instrument worked and how they would help correct her poor eyesight. “And that reassuring voice helped a lot,” Ziebarth recalled of the first time she ever saw an ophthalmologist.

While her anxiety waned, her curiosity grew. Suddenly, she wanted to know everything there was to know about the human eye—how it works, why some people see better than others, and what causes blindness.

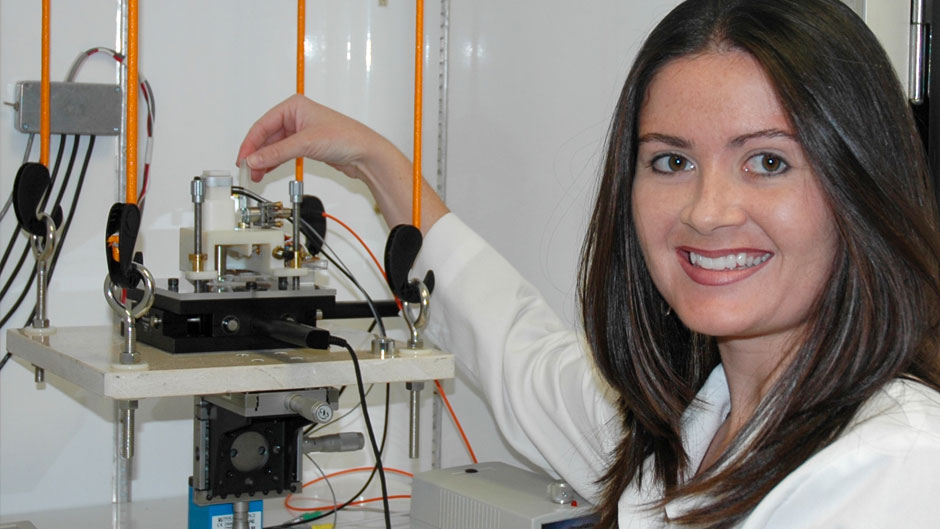

Today, as an associate professor of biomedical engineering in the University of Miami College of Engineering, Ziebarth is still fascinated with the eye. Only now, her spirit of inquiry has led to groundbreaking research that is not only helping people to see better but also aiding in the discovery of treatments that will allow the sightless to see again. “I want my research to impact people’s lives and help make a difference,” Ziebarth said.

A triple ’Cane—she earned her bachelor’s, master’s and Ph.D. degrees from the University—Ziebarth directs the Biomedical Atomic Force Microscopy Lab on the Miller School of Medicine Campus, where she uses confocal, atomic force, and scanning electron microscopes to analyze the lens, cornea, and retina of the eye in its normal and diseased states.

She is especially interested in alternative treatments for cataracts, the clouding of the normally clear lens of the eye. “Cataracts is an age-related condition,” Ziebarth said. “If we can delay its onset, it would be much less of a burden on many people.”

So, she is looking closely at a membrane that surrounds the lens and becomes thicker with age, theorizing that its increased density actually prevents anti-cataract drugs from being effective. Perhaps, she surmises, there is a way of delivering a therapeutic agent to the membrane that would decrease its thickness, allowing drugs to reach their intended target.

Her lab is studying such drug-delivery techniques as a way to treat another eye disorder—keratoconus, in which the cornea, the transparent layer at the front of the eye, thins and gradually bulges outward into a cone shape, causing blurry and distorted vision. “We’re looking at corneal cross-linking, combining riboflavin [vitamin B2] drops with ultraviolet light to strengthen the cornea,” Ziebarth explained.

She is carrying that research even further, trying to determine the effectiveness of different iterations of that combination technique. “How long should it be done? Can we do it faster? Is it more effective if we pulse the light? There are so many versions of just that one treatment alone,” Ziebarth said. “But it comes down to the characterization of how stiff the cornea is getting. Is it returning to its normal level? Is it 50 percent of what it was? We’re quantifying different techniques and seeing how good they are at bringing the cornea back to what it was.”

High-resolution images provide Ziebarth with the information she needs. Her research, she said, wouldn’t be possible without the powerful atomic force microscopes that produce those images. So, she’s become adept at building them, having some of the parts fabricated at the Johnson & Johnson 3D Printing Center of Excellence Collaborative Laboratory at the College of Engineering.

Collaboration, Ziebarth said, is one of the lynchpins of her research, allowing her to be an important team member in bringing important medical advancements from the bench to the bedside. She has worked with Sonia Yoo, professor of ophthalmology at Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, on several corneal research projects, one of which resulted in the approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for a new and better version of LASIK eye surgery. “That is what’s critical about biomedical engineering. We form interdisciplinary teams with physician-researchers and work together to have success,” Ziebarth explained. “We bring the technology to the table; they bring another aspect—whether it’s biochemistry or immunology.”

She is especially excited about an upcoming collaboration with Noam Alperin, a Miller School of Medicine professor of radiology and biomedical engineering. The two and others will investigate why astronauts develop visual impairments after extended-duration missions such as those aboard the International Space Station.

“The focus has always been on the changes to bone density, muscle mass, and cardiovascular health after long-term exposure to microgravity,” Ziebarth said. “But it’s just as important to find out why astronauts experience blurry vision after long-duration space missions.”

With the COVID-19 pandemic still surging, an opportunity to investigate how the virus might affect eyesight could arise in the near future, Ziebarth noted. She recalled how the American physician Ian Crozier, who contracted Ebola in Sierra Leone, where he worked at a hospital, was treated for and declared free of the disease in 2014 but later experienced eye problems. Tests revealed Ebola was still present in his eye. “In-depth studies on how the coronavirus affects eyesight are coming; I’m sure,” she said. “There’s already evidence that these types of diseases remain in the eye longer.”

Ziebarth said she will never tire of conducting research. “Seeing the whole process start from an idea and progress toward actually helping someone—that’s what I enjoy most about my work.”