The team’s pregame meal had ended only a short while ago, and 19-year-old Jim Kelly, like the rest of his Miami Hurricanes teammates, started to prepare for the squad’s game against vaunted Penn State. Then came the tap on the shoulder that would change Kelly’s collegiate career.

Howard Schnellenberger, an imposing figure with a baritone voice who had arrived at the University of Miami with an ambitious goal of winning a national championship within the first five years of his head-coaching tenure, had pulled Kelly aside to tell the then-freshman that he would get his first collegiate start at quarterback against the nationally ranked Nittany Lions.

“As we’re walking, he [Schnellenberger] said, ‘Son, I decided that you deserve the opportunity…Get yourself ready,’ ” Kelly recalled. “Well, I got myself ready. I excused myself, went into the bathroom, and threw up.”

Kelly’s pregame jitters were not the result of fear or the feeling that he lacked what it took to guide the Miami offense. Leadership skills had been engrained in Kelly long before that 1979 road game, which the Hurricanes won 26-10. “How I really learned all the things I’ve used throughout my life started with my father raising six boys and teaching us hard work, discipline, and leading by example,” Kelly said Tuesday.

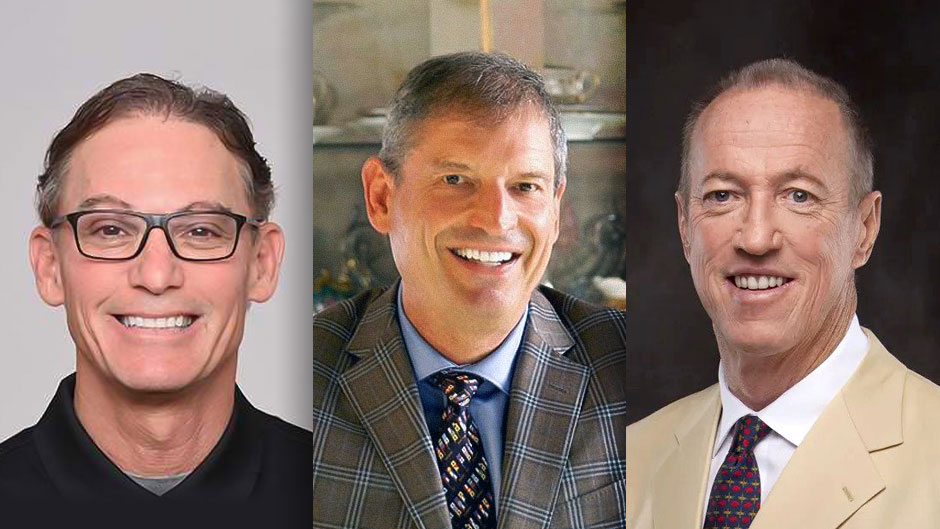

His comments were part of the virtual event “Defining Your Leadership Playbook.” Hosted by the University of Miami School of Law’s Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law (EASL) LL.M. program, the fireside chat also featured former Hurricane quarterback Bernie Kosar—who led the Miami program to its first national championship against Nebraska in 1984, fulfilling Schnellenberger’s mandate—and former assistant Marc Trestman, the quarterbacks coach of that legendary Miami team. The forum, which was moderated by Peter Carfagna, co-director of the sports law track, also served as the launch event for a new sports leadership course that will be taught at the law school this spring.

“Great leaders on the field and in their communities” is how Greg Levy, director of the EASL program, described the three fireside chat participants.

Kelly, who passed for 5,228 yards and 33 touchdowns during his four years with the Hurricanes and went on to a stellar NFL career, leading the Buffalo Bills to four straight Super Bowl appearances, said he learned a lot about leadership by just listening to his East Brady, Pennsylvania, high school coach, Terry Henry, and observing his wife, Jill, as she helped lead the Kelly household during the Hall of Fame quarterback’s bout with cancer.

“It’s not always what you’re saying. It’s how you listen and how you develop, whether it’s in the classroom, in the huddle, or on the football field,” Kelly said. “When people are listening to you and you are listening back, and you don’t always have something to say but you open your ears—that’s how I developed everything. But it all started as a little kid with a great father and five brothers.”

Trestman learned about leadership through failure. “For years, I drifted in the wind from job to job for all the wrong reasons,” said the 1982 graduate of the School of Law, who won three Grey Cup titles as a head coach in the Canadian Football League and held several positions with NFL teams, including as head coach of the Chicago Bears.

He said he hit rock bottom in 2006, when, as offensive coordinator of the North Carolina State University football team, he and the entire coaching staff were fired at the end of the season. “The good part about it was I was fired with two years left on my contract, which gave me time to read and to network and to find out why, when I looked closely at myself, there was really no personal fulfillment,” Trestman said.

He created a narrative of his life, discovering that the goal of getting a better job title, earning more money, and obtaining economic security and peer-group acceptance “wasn’t the road to success, true happiness, or personal fulfillment,” he remembered. “I discovered my ego, my immaturity, and lack of self-awareness were really my enemy.”

He’d just turned 50, and looking back on his life “helped me crystalize my new purpose of not coaching transactionally, like using players as chest pieces to score touchdowns or get results on the scoreboard.”

Trestman instead became what he called a “transformational” coach, developing good personal relationships, helping others to self-actualize, and serving people without the expectation of something in return.

Kosar, who was drafted by the Cleveland Browns and won a Super Bowl ring as a backup quarterback on the 1993 Dallas Cowboys team led by former Hurricanes coach Jimmy Johnson, said his leadership style developed from paying attention to small details, an attribute he learned from those who coached him throughout his playing days.

“How you do little things is how you do all things,” Kosar said. “So many times today in society, we start thinking about the bigger picture too far down the road. We forget to do what’s right in front of us—taking care of the little things. When you have the type of mindset where you’re results-oriented, that helps unify and bring us all together as a team, as a family.”

Kosar bemoaned the fact that technology—miniature receivers and speakers inside helmets that allow some players on the field to communicate with coaches on the sideline—sometimes takes the decision-making process and leadership skills away from today’s NFL quarterbacks. “In the old days, we called our own plays. We had help from the sideline, but we were taught how to call plays. We weren’t told what to do,” he explained.

“The coaches taught me that when you go out onto the field, you are the last person to see the safeties, the last one to see the defense,” Kosar continued. “We’re going to teach you enough so that you have the ability to make the decisions yourself and lead and tell everybody else what to do. It’s important for older people to relinquish control sometimes and have confidence in the people around us. That type of teaching resonates within my DNA now.”

The three University of Miami alumni also reflected on what they remembered most about the coaches in their lives.

When Schnellenberger spoke, “people shook,” Kelly said, referring to the respect the now-retired coach commanded. “I can see why he’d wind up winning a national championship and putting Miami back on the map.”

Schnellenberger still commands respect, Kosar said. “If he says to be somewhere, still, at our ages, we show up,” he said.

Johnson, Trestman recalled, was “eternally optimistic and passionate. I saw his big heart, and I think a heart is what every great leader has.”

But it was the way Johnson could motivate his players that was arguably his greatest leadership attribute, Trestman said. “He got to know them. He developed relationships with him. He found true value in them, and that allowed him to get the best out of his players. He was a master at that.”

Johnson instilled “youthful enthusiasm and passion,” Kosar remarked, saying the legendary coach made them feel “there was no way we could lose.”

Sometimes, though, the greatest leadership lessons in life for the three came from those who never coached. Like Kelly’s son Hunter, who died at the age of 8 from the fatal nervous system disorder Krabbe disease. “Seeing Hunter battle taught me that I didn’t have it that bad,” Kelly said.