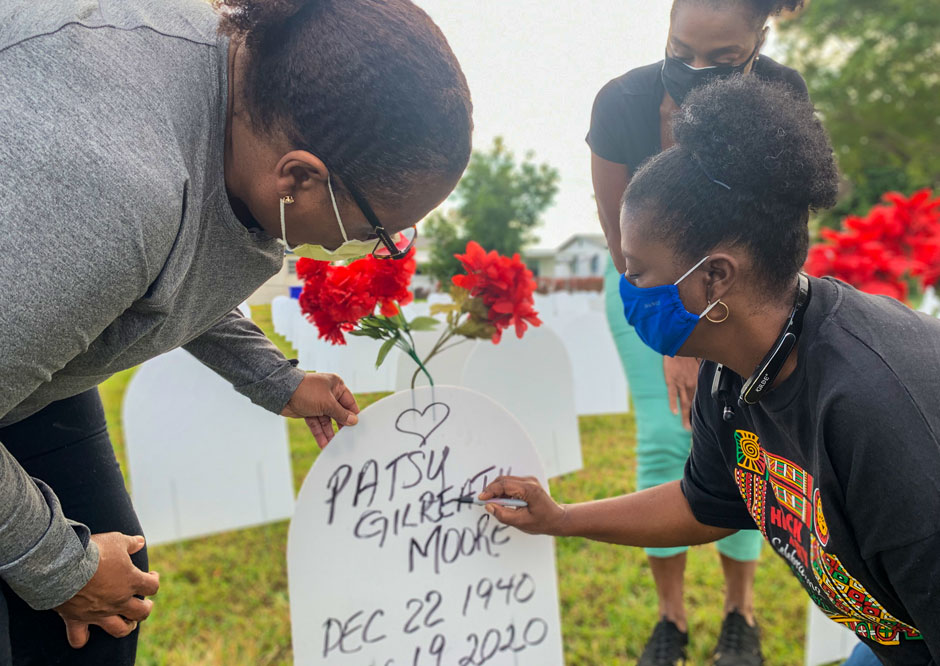

On the last day of her life, 79-year-old Patsy Gilreath Moore said goodbye to her three daughters while lying in the ICU ward of a Broward County hospital. She couldn’t embrace them, as she had done so many times before. Instead, Moore listened to the voices of the three “jewels of her life” through a 13-inch iPad.

Like so many other COVID-19 patients who have spent their last days in a hospital bed, Moore was not allowed to have visitors—a measure taken by many health care facilities across the nation to minimize the risk of spreading the virus.

But even in her death, Moore, who was a Miami-Dade educator for nearly 40 years, has a valuable lesson to teach—that the COVID-19 vaccines will help bring an end to a devastating pandemic that has now taken nearly 450,000 lives in the United States.

“That would have been her message,” said Moore’s daughter, Angela, a surgical nurse at Jackson Memorial Hospital. “If she were alive today, she would have been first in line to get the shot. She would have said that the pain of a loved one taking their last breath and not being able to say goodbye to family members in person is just too heartbreaking, and that if the vaccine can prevent that, we all need to roll up our sleeves and get it.”

That may prove a difficult message to get across to some groups. According to a recent Kaiser Family Foundation survey, about 35 percent of Black Americans, a group disproportionately affected by the coronavirus, said they definitely or probably would not get the COVID-19 vaccine.

Mistreatment yields mistrust

Indeed, skepticism over the vaccine runs deep in many communities of color—a mistrust fueled in part by a long history of medical mistreatment.

One example was the injustice of the Tuskegee syphilis study, where a group of 600 mostly poor Black men from Macon County, Alabama, were told they were being treated for “bad blood.” They were promised free health care and free meals. But what they were not told was that they were human guinea pigs, subjects of a government-backed study to track the progression of untreated syphilis.

A total of 399 of those men had syphilis, yet even when penicillin became the standard treatment for the deadly venereal disease in 1947, they were denied the antibiotic. Dozens died. And the study, which began in 1932, didn’t end until 40 years later, when the press exposed it.

The “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male by the U.S. Public Health Service” is the example most often cited to explain the mistrust some Black Americans harbor toward the vaccine. But in reality “there are a multitude of reasons built into that lack of trustworthiness,” said Sannisha Dale, a health psychologist in the University of Miami College of Arts and Sciences.

“It’s not just Tuskegee,” Dale explained. “If you ask some Black Americans about their views around the vaccine or their views around medicine and their trust towards doctors and institutions, there’s going to be a level of cautiousness, and a big part of that stems from what historical trauma looks like and what discrimination looks like on a day-to-day basis. It hasn’t been that long ago that Black Americans would show up at hospitals and be turned away because it was segregated.”

Debunking the myths

Olveen Carrasquillo, a Miller School of Medicine physician and researcher, calls them “conspiracy-fueled myths”—wild theories about the coronavirus vaccines that are “coming from who knows where.”

There are rumors like the one about the vaccines containing small robots or computers. And others that say the vaccinations are embedded with tracking chips that would be activated by 5G wireless technology.

Whatever the case, such misinformation is helping to fuel hesitancy about the COVID-19 vaccines among some groups. But Carrasquillo, chief of the Division of General Internal Medicine who led one of the trials for the Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine, is doing something about it. Using education and outreach, he is spearheading a National Institutes of Health-funded statewide study that is devising strategies to dispel erroneous information about the vaccines and, more importantly, answer the legitimate questions many people have.

“There are certain community enclaves in Miami that are more isolated, and they’re getting information from sources that are harder for us to tap into and to counteract,” said Carrasquillo, who is also co-director for community and stakeholder engagement at the Miami Clinical and Translational Science Institute. “In addition to conspiracies, there are also the legitimate questions that we can address: How were the vaccines developed so quickly? What are the side effects? Will I be a guinea pig?”

His research group has successfully brought community leaders and partners onboard, organizing online focus groups and surveys to find out what people are saying and then rolling out content that successfully addresses community concerns.

One positive sign that should help quash the miscommunication and persuade more groups to trust the vaccines are the scores of health care workers, from doctors to nurses, who are setting an example by being among the first to get inoculated. “It’s having a positive impact,” said Carrasquillo, a national expert on minority health and health disparities. “I’m a lot more optimistic today than I was a few weeks ago.”

The 3 Cs Model

Vaccine hesitancy isn’t specific to any one segment of the population. Other groups have expressed a disbelief in the vaccines as well. It is a mistrust influenced by three factors the World Health Organization has identified as confidence, complacency, and convenience, said Eric C. Brown, an associate professor of public health sciences at the Miller School of Medicine.

“Confidence refers to a lack of trust in the safety and effectiveness of a vaccine and a lack of trust in the system that would deliver it,” explained Brown. “Complacency is where the risks of disease are determined to be low. To some people, the vaccination is not really necessary or a high priority. They’re complacent about COVID-19 in general and think the numbers are exaggerated,” he added. “Then there’s convenience. If it’s not convenient to get the vaccine, people aren’t going to get it. The vaccine has to come to us, to our neighborhood, or local Walgreens. And it has to be done in a way that’s amenable.”

Brown, who directs the Ph.D. program in Prevention Science and Community Heath, has extended that so-called “3 Cs model,” adding a fourth factor—culture. “Here in Miami, one big issue of culture is language,” he explained. “Are people getting information [about the vaccine] in Spanish, in Haitian Creole, or in whatever language they speak? And What about family history? Perhaps someone in a Latinx family had a very bad experience with a government-led health campaign, and that history carried over from generation to generation and worked its way into the culture as being part of distrust.”

Culture, Brown said, is also intertwined with socioeconomic status. People who are poor will likely put other high-priority responsibilities—such as buying food and caring for children—above getting vaccinated.

New techniques for the flow and dissemination of data on vaccines need to be implemented, allowing people to access critical information much faster and for interventions like inoculations to take place, Brown said. And that’s where the Vaccine Considerations Project, in which he is involved, comes into play.

Created by Jared Krupnick, an aerospace engineer, website programmer and the founder of Uniting for Action, the initiative uses crowdsourcing techniques to collect and organize relevant vaccine-related health and safety concerns being expressed by medical professionals, epidemiologists, public health experts, and scientists. It then shares that information with anyone.

“The flow of information is no longer linear; it’s simultaneous. Everyone can put information in and take information out,” Brown said. Students in his Disease Prevention and Health Promotion class are playing a key role in the project, examining and prioritizing information that’s being submitted.

Jasmine Nicole Jackson, a first-year master’s student in the public health science program and a former Peace Corps volunteer who worked for six years in Malawi, said gathering and curating data for the Vaccine Considerations Project has been as much a benefit for her as it has been for those who are accessing the website. “I’m on the fence about the vaccine and so are my parents,” Jackson revealed. “This project is getting information out and in a way people can relate to and understand and not feel cut off from the science.”

Understanding the Science

Trusting the science that went into creating the vaccines is critical to building trust. “It’s understandable that people will have questions about new interventions and new treatments before enthusiastically jumping in,” said Susanne Doblecki-Lewis, associate professor of clinical medicine, clinical director of the division of infectious diseases, and principal investigator of the Moderna COVID-19 vaccine trial at the University of Miami. “Of course, groups that have experienced real trauma in the medical establishment before are going to have more questions. We have to acknowledge that history. For everyone, it’s about having an open conversation and being transparent about what we know and what we don’t know.”

Doblecki-Lewis said it is important to remember that the vaccine has already gone through rigorous clinical trials and is now in a different phase. “It’s true that we don’t have long-term data. That will eventually come. But we do have quite a bit of information about the safety and efficacy of these vaccines,” she said.

She praised the many volunteers who participated in the trials, calling them the unsung heroes of the project. “No one would be getting vaccines today if it weren’t for them. They made it happen and are continuing to play an important role as we continue to find out other things that are very important. It’s great that the vaccines work, but we all want to know for how long.”

While the vaccines will help all groups, the conversation has to move beyond the science and address those issues that have plagued Black Americans and other marginalized groups for decades, health psychologist Dale said. “We need to have a conversation about housing, about employment, about emergency funds that people need to make it through this pandemic,” she stated. “To say to a community that we care, and we see how you’re being devastated, is to say that we see you holistically and we see all of the issues that this pandemic has exacerbated and brought to the forefront.”

One of those issues: the roadblocks Black Americans who want to get the vaccine are encountering.

“The zip codes that are heavily hit by COVID-19 and are home to many Black individuals face structural barriers such as the absence of health care facilities and inadequate public transportation infrastructure,” Dale said. “Equitable access to the COVID-19 vaccine will entail bringing the vaccine to Black communities, financially supporting Black-led efforts, listening to and genuinely partnering with community members, and constantly aiming to address the structural inequities that unleashed the burden of the COVID-19 pandemic on Black communities.”

And the work to address such inequities has to be informed by community leaders, whether it be trusted medical professionals or ministers preaching from the pulpit, she said.

Richard Dunn, pastor at Faith Community Baptist Church in Miami, knows that better than anyone. He is part of an alliance, Keeping the Faith, that has organized COVID-19 testing at Black churches and other sites in the county, and which is partnering with local physicians to help educate minority communities about the vaccines.

“We’ve had parishioners who have contracted the virus. We’ve had a longtime deacon who died from the virus. Yet many of the seniors I know, either through the church or in the community, are reluctant to get the vaccine,” Dunn said.

“So, when my time comes to get vaccinated, I’ll be excited to get the shot. It will hopefully serve as an example that it’s something we all need to do to help achieve herd immunity,” Dunn said, adding that he plans to post a short video of his vaccination on his church’s Facebook page.

Angela Moore and her two sisters, Rachel and Joanna, said they will forever try to live up to the example set by their mother.

“She watched the news every day, keeping track of the progress of vaccine development,” Rachel said. “She knew lives were on the line.”