As a member of the Cuban American community, Marian Pedreira has heard plenty of reasons why residents in Miami-Dade County are refusing to get the COVID-19 vaccine.

In March 2021, when new variants were posing a threat to the return of a normal society, Pedreira jumped at the opportunity to become an Interfaith Youth Core (IFYC) Faith in the Vaccine Ambassador (FIVA) to debunk the myths and help inform members of her community.

The FIVA initiative is an outreach program through IFYC which mobilizes college students across 108 campuses and more than 90 civic and faith-based institutions. Vaccine ambassadors’ projects were funded by a grant from IFYC, a national nonprofit with a mission to move closer to an America where people of different faiths, worldviews, and traditions can come together and find common values and share a life.

“The people around me are the whole reason I decided to become a vaccine ambassador,” said Pedreira, who is a senior studying neuroscience and on the premedical track. “There is just a lot of distrust over getting it and amongst populations that are very vulnerable—like a lot of elderly Hispanic individuals I know, who have a lot of comorbidities like obesity, diabetes, and other underlying conditions.”

Ashmeet Oberoi, clinical assistant professor in the Department of Educational and Psychological Studies in the School of Education and Human Development, is the principal investigator of the grant. She, along with Office of Multicultural Student Affairs (MSA) leaders Christopher Clarke and Kennedy Robinson, recruited and oversaw 17 University students to participate in the FIVA program and provided them with IFYC-led training curriculum. They then took things a step further by designing and providing training in diversity, equity, and inclusion topics based on the communities they wanted to engage with.

“We coached students in identifying goals for their projects and developed project plans and activities to achieve and complete these goals,” said Oberoi, who is a member of University President Julio Frenk’s Standing Committee on Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion, which has been reinvigorated as part of the University’s racial justice plan.

Though members of the Black, Native American, and Hispanic communities have been hit the hardest by COVID-19, these are also the same groups that are less likely to trust the vaccine. With all the tools provided—such as materials available in English, Spanish, and Creole—the cohort of students used various methods to address members of these communities directly.

“Alongside emergency medicine physicians, I volunteered at community events to talk with members of the community and convince them to get the vaccine. But more importantly, it was good to meet them at a place of understanding and to provide them with all the information, so they can make the best decision for themselves,” said Pedreira. “Throughout this project, I’ve learned a lot about just how even though there are different social identities surrounding hesitancy for the vaccine, they intersect a lot.”

Robinson said now that the projects have concluded, they have data to show how University students helped to enhance or increase vaccine awareness and increase the number of vaccinated people in various racial, elderly, and religious communities in Miami-Dade County.

“Marian [Pedreira] has continued to work at health fairs and recently presented with MSA at the Housing and Residential Life social identities event,” said Robinson. “She’s done a great job. Each student really rose to the occasion and came up with such amazing ideas to reach their intended communities.”

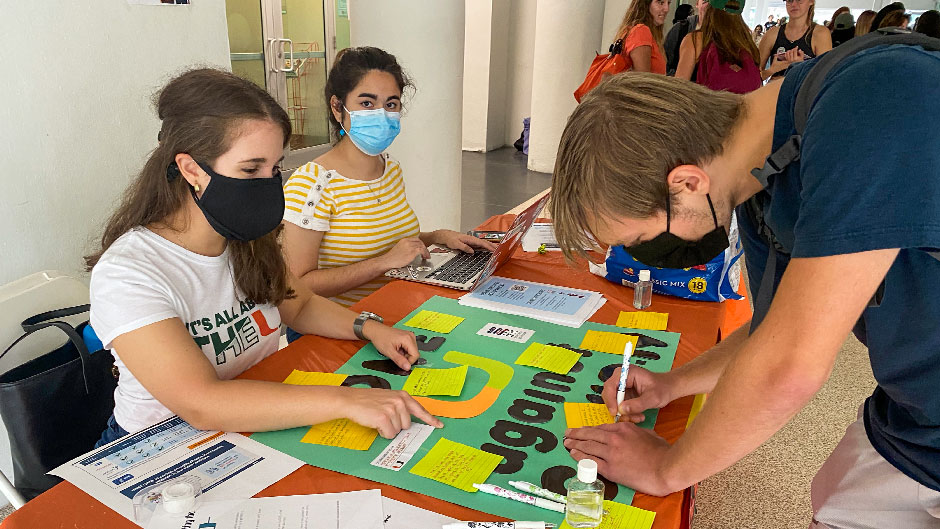

From setting up tables on campus, in local churches, in mosques, and in medical facilities, all projects within the cohort aimed to upturn trust in the vaccine, advance access to it, and/or tackle any doubt toward it.

Oberoi and the MSA team noted that they are extremely proud of the work each student provided throughout the semester. Oberoi’s hopes for the project came to fruition, and she will continue to address racial disparities and social inequities through her work.

“I saw it as an opportunity to make an impact or a difference by training students to use strategies from community-based methods to work with diverse communities and to mitigate the effects of social inequities and racial and religious disparities in the uptake of the COVID-19 vaccine,” said Oberoi. “At the same time, I believe in building multi-sectoral partnerships on campus for creating opportunities for students to engage in community-based, service-learning projects, so I reached out to Ms. Kennedy Robinson and Mr. Christopher Clarke at MSA to be my partners—or co-investigators—on this grant.”

Pedreira said the project has led her closer to her dream of one day starting a career in public health and medicine. She hopes that the work her cohort delivered also inspires younger students to go into their communities and spark positive changes.

“I will definitely incorporate all of the skills I gained moving forward,” said Pedreira. “I learned a lot of information about the vaccine and especially how to communicate to others in a way that meets them at a place of inquiry, and not shy them away from learning.”