Hit the repeat button. Another busy Atlantic hurricane season is in the cards.

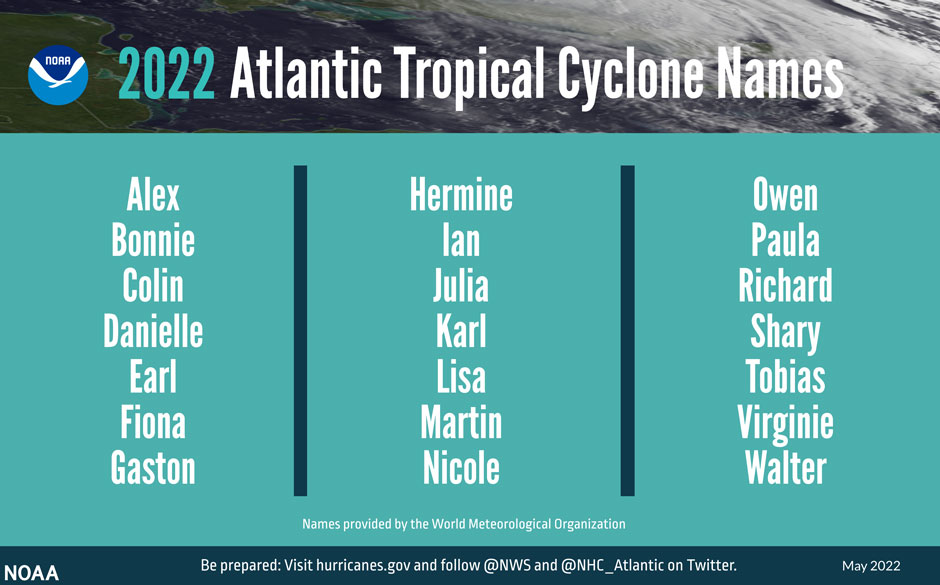

In its annual seasonal outlook, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Climate Prediction Center has forecast yet another above-average hurricane season, with 14 to 21 named storms, of which six to 10 could become hurricanes, including three to six major cyclones with winds of 111 miles per hour or higher.

If NOAA’s prediction holds true—the agency provided the ranges with a 70 percent level of confidence—it will mark the seventh consecutive year for an above-normal season.

An ongoing La Niña, the periodic cooling of sea surface temperatures in the eastern tropical Pacific, is among several climate factors that point to a busy season, said Ben Kirtman, a professor of atmospheric sciences at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science.

The phenomenon can increase hurricane activity in the Atlantic by weakening wind shear over the Caribbean Sea and tropical Atlantic Basin, allowing storms to develop and intensify. “On the other hand, there is a lot of Saharan dust in the Atlantic that suppresses hurricane formation,” Kirtman explained. “But the dust should clear out in the next few weeks so that the La Niña effects win out.”

Warmer-than-average sea surface temperatures in the Atlantic and Caribbean Sea, weaker tropical Atlantic trade winds, and an enhanced west African monsoon are among the other indicators that make an active season likely, according to NOAA.

The Gulf factor

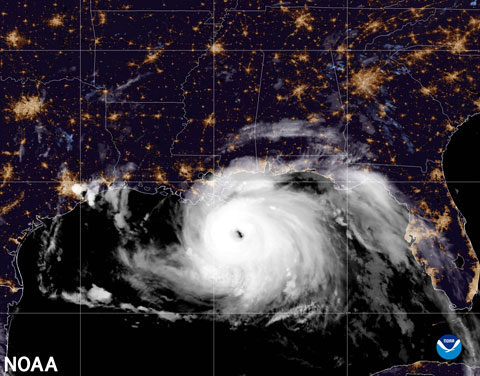

A partially landlocked body of water that Rosenstiel School physical oceanographer Lynn “Nick” Shay has been watching closely—even before the start of this hurricane season—is the Gulf of Mexico, where unusually high temperatures could be a portent of what’s to come for the 2022 Atlantic hurricane season.

Shay, who has been studying the dynamics of tropical cyclones for more than four decades, is particularly concerned about the Loop Current, an area of warm water that travels up from the Caribbean, past the Yucatan Peninsula, and into the Gulf. The current is known to shed massive eddies that retain considerable amounts of heat.

“Tropical storms that pass over the Loop Current or one of its giant eddies can become turbocharged as they draw energy from the warm water,” explained Shay, professor of ocean sciences and associate dean of research. That’s what occurred last season when Hurricane Ida passed directly over an eddy with surface temperatures over 86 degrees Fahrenheit, Shay discovered. The Category 4 storm, which made landfall near Port Fourchon, Louisiana, on the 16th anniversary of Katrina, moved all the way up to Connecticut, causing dozens of deaths and $75 billion in damage, making it the fifth-costliest hurricane on record in the United States.

And this year, Shay pointed out, the Loop Current looks astonishingly like it did in 2005, the year Katrina crossed the current before devastating New Orleans. Until the record-breaking 2020 season, 2005 was the most active year for Atlantic hurricanes in U.S. history, producing 27 named storms, of which seven became major storms. That year, hurricanes Wilma and Rita also crossed the Loop Current, Shay noted.

Tropical cyclones acquire most of their muscle from the top 100 feet of the ocean. “Ordinarily, these upper ocean waters mix and allow warm spots to cool rather quickly,” Shay said. “But the Loop Current’s subtropical water is deeper, warmer, and saltier than Gulf common water. And these conditions hinder ocean mixing and sea-surface cooling and allow the warm current and its eddies to retain heat at tremendous depths.”

Satellite telemetry from mid-May revealed the Loop Current had water temperatures of 78 degrees Fahrenheit (the threshold at which tropical cyclones strengthen into hurricanes) or warmer down to about 330 feet, Shay reported. “That heat could extend down to around 500 feet by summer,” he said.

This season, he will monitor the Gulf’s heat content in a variety of ways, deploying Autonomous Profiling Explorer floats with electromagnetic sensors from C-130 Hercules aircraft based at the U.S. Air Force’s 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron out of Keesler Air Force Base in Biloxi, Mississippi.

The 70-pound five-and-a-half-foot-long floats, which can measure temperature, salinity, current, and pressure at depths as low as 2,000 meters, will likely be deployed with satellite drifters from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography and with Alamo Floats from the U.S. Naval Academy and Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

Shay and his team will also deploy about 200 expendable profilers out of the NOAA Hurricane Hunter aircraft, measuring temperature, salinity, and current at depths of 1,500 meters.

The cone of uncertainty

NOAA’s latest hurricane forecast comes after a busy 2021 season that produced 21 named storms, with eight landfalling tropical cyclones affecting the U.S.—two hurricanes and six tropical storms.

“Florida was the recipient of three of those tropical storm landfalls, but they were all up in the Panhandle,” said Brian McNoldy, senior research associate and tropical cyclone expert at the Rosenstiel School. “The Florida Peninsula escaped significant impacts, although the Tampa area had a close call with Hurricane Elsa just offshore. Given the highly variable steering currents from one day or week to the next, I think it mostly comes down to luck that South Florida remained clear.”

When cyclones develop in the Atlantic or Gulf, coastal residents typically keep a watchful eye on the cone of uncertainty, the probable track of the center of a storm that is produced by the National Hurricane Center and featured prominently by television meteorologists during their hurricane coverage.

The size of the cone, which is updated each year and includes track-error statistics from the previous five years, has gotten smaller over the past two decades because of sustained investment in research, model development, and the evolution of supercomputer facilities, according to McNoldy.

“Unfortunately, as time goes on, further reductions [in the size of the cone] become harder and harder to achieve,” he explained. “The atmosphere is a chaotic system, so it can never be predicted with certainty, and there is a limit of predictability that will eventually be reached.”

The cone, McNoldy cautioned, is designed only to illustrate uncertainty in the track of the center of the storm and does not tell us anything about a storm’s size or where impacts will be experienced. “The cone flares out in size at longer forecast times because the track forecast inherently becomes more uncertain the further out in time you go,” he said.

NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center will update its 2022 Atlantic seasonal outlook in early August, just prior to the historical peak of hurricane season.