In the past few weeks, cases of the monkeypox virus have started spreading across the globe. The World Health Organization (WHO) reported 92 confirmed cases and 28 suspected cases of the rare virus on Monday in 12 countries, with the majority clustered in Spain, Portugal, and the United Kingdom. Canada also has a handful of cases.

Last week, a Massachusetts man was the latest confirmed case in the United States. On Sunday, a suspected case was found in Broward County, with a second presumed case announced on Tuesday.

First identified in Africa more than 50 years ago, experts believe the monkeypox virus transferred from a primate or rodent to a human. However, since monkeypox is not a respiratory virus and is typically spread through saliva or bodily fluids, experts believe it will not become as contagious as COVID-19.

Two infectious disease experts at the Miller School of Medicine describe what they know about the monkeypox virus. Dr. Maria Luisa Alcaide is a professor of clinical medicine in the division of infectious diseases, director of clinical research at the Miller School, and directs the clinical core and mentoring program at the Center for AIDS Research. Professor Mario Stevenson is a renowned expert in molecular virology in the division of infectious diseases and is the Raymond F. Schinazi and Family endowed chair of biomedicine. He also co-directs the Center for AIDS Research.

What is monkeypox and how long has it been around?

Alcaide: Monkeypox is a virus that typically infects animals, and it has been identified in animals in central and west Africa. Cases in humans are rare and usually happen when people are in contact with animals. Most of the cases we have seen outside of Africa were cases where people were traveling to Africa, or animals from Africa were brought to the U.S. and infected humans. Until recently, the virus hasn’t been known to transmit from human to human. Although, it seems like that is happening now and that’s why we are concerned. Over the past few weeks, there has been an unusual number of cases reported in humans.

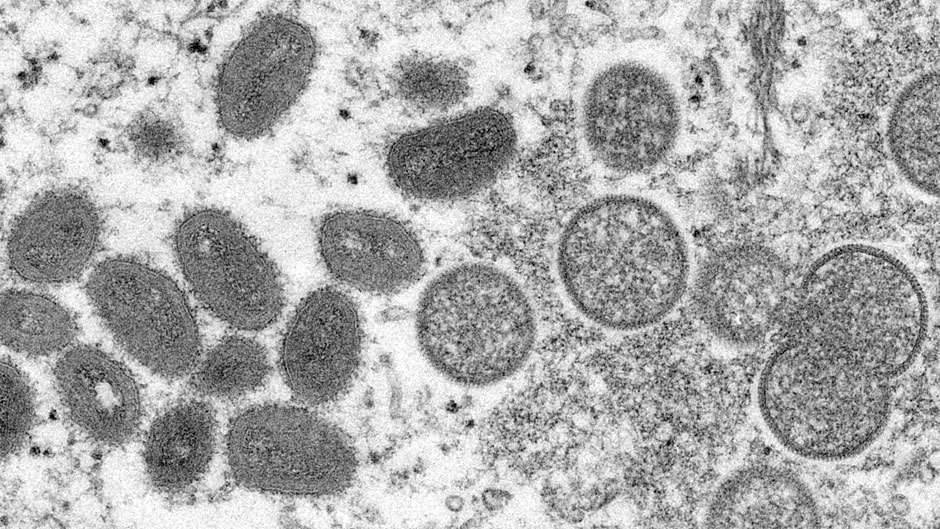

Stevenson: First of all, monkeypox is a DNA virus and that’s a good thing because they tend not to mutate. They are nothing like RNA viruses, such as the novel coronavirus, or HIV, or influenza. Therefore, we don’t expect there to be a whole lot of monkeypox viruses to evolve and stop vaccines from working.

The first identified case of monkeypox in humans was in 1970, and likely came from a person working in the logging industry in Africa who came across a primate and butchered it—without knowing the animal had a virus.

The first monkeypox outbreak was from 1981 to 1986 in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where there were several hundred cases with a 10 percent mortality rate. The second outbreak of monkeypox occurred from 1996 to 1997, also in the Congo, with a smaller mortality rate of 1 percent. That was about 500 cases. The third outbreak we know of happened in the United States around 2003 when a Texas pet distributor imported some pouched rats from Ghana, and one bit a child. Within a few months, there were 70 cases, but there were no deaths or fatalities.

And although monkeypox is in the same family of viruses as smallpox, which was eradicated in 1980, monkeypox is much less severe.

How is it transmitted?

Alcaide: We are looking for these answers now. When epidemiologists looked at many of the recent cases in Europe, they found some common links. It looks like some—not all—of these cases were found in men who have sex with men, who may have visited places that are common vacation spots.

In general, the virus is usually transmitted through saliva droplets or skin to skin contact with monkeypox lesions, which are filled with liquid. Typically, monkeypox is not considered a sexually transmitted infection. But because of the recent cases in men, it’s being considered transmitted where there has been intimate contact.

How contagious is it?

Alcaide: This is not a respiratory virus—like COVID-19—so it is not as contagious. The main mode of transmission for monkeypox is direct contact with saliva or monkeypox lesions. If this occurs, symptoms will develop pretty quickly, like malaise, fever, and then a rash develops—which are pustules (bubble-like wounds) with liquid inside. It’s kind of like chicken pox, but the pustules are larger, and monkeypox lesions can last up to two weeks. Some can heal while others are appearing, and people can get the lesions anywhere. They often appear in the palms of the hands and on the arms, then they can spread anywhere on the body. Generally, people are considered contagious until all the lesions are gone, and they can be itchy.

Stevenson: There is some evidence that monkeypox can be aerosolized, so people in the same household may be at risk, but this is a continually evolving story.

How does the virus progress?

Alcaide: If we see more cases, we will know more. But as of now, we believe that people often feel bad for a few days with fever, malaise, and headache, and then lesions will appear. However, we don’t know exactly, because we have only seen a handful of cases.

Stevenson: Typically, it starts with fever, muscle aches, headache and/or swollen glands, and the rash will show up within one to 10 days.

Do you expect monkeypox to spread more?

Alcaide: Right now, the number of cases is limited. And as we identify cases, they are relatively easy to isolate, which is reassuring. It’s concerning enough that doctors should be on the lookout for fever and a rash that looks like monkeypox, but it is too early to believe this will be widespread. We need to see what’s going to happen over the next few weeks and months.

The good news is, the majority of people recover from monkeypox, but it’s not a virus for which we have a lot of data.

Stevenson: No. We had an outbreak in the Midwest in the early 2000s and it did not spread beyond 70 people, and now we all have a heightened awareness of infectious pathogens because of the coronavirus. So, it makes people more aware of their illness and more likely to go to a doctor or health care practitioner if they aren’t feeling right, or if they get a rash. Also, it is easier to identify people who are infected with monkeypox. And they should be isolated and contact traced. These public health measures did not work well for coronavirus because lots of infections had little or no symptoms.

Plus, there are treatments for monkeypox available. There is a drug called Tecovirimat, also known as TPOXX, that is an antiviral and is known to combat monkeypox, cowpox, and smallpox. There is also evidence that people vaccinated for smallpox in the 1970s may have some protection against monkeypox. In addition, there was a vaccine approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in 2019, called Jynneos, that can protect people against smallpox and monkeypox.

What can people do to protect themselves?

Stevenson: Someone who has come back from a trip to an exotic location or from a place with documented cases of monkeypox want to be extra aware of their symptoms if they get sick.

Alcaide: If you or a family member is experiencing symptoms, seek medical attention.