When Jacques Calixte was starting elementary school, his parents surprised him with a doctor costume for Halloween.

Calixte, whose parents immigrated to South Florida from Haiti, believes it was their way of encouraging him to excel in school. But it also piqued his interest in health care.

That interest continued at Immaculata-La Salle High School, where he joined a STEAM program that allowed him to shadow doctors at Mercy Hospital in Miami. As a pre-medical student at the University of Miami, he became one of the first public health ambassadors during the COVID-19 pandemic. Calixte then gained research experience in the University’s biology department that propelled him toward other clinical experiences and research labs at medical institutions across the country.

Today, Calixte is even more passionate about medicine and hopes to become a cardiologist, treating patients from a variety of backgrounds, while also conducting research.

“In college, I’ve been able to explore the medical field, experience patient encounters and see what doctors really do day to day,” said Calixte, who is majoring in philosophy, with a minor in chemistry in the College of Arts and Sciences. “But after realizing that I wanted to be a cardiologist, I’ve also recognized that one day I would like to have a more dynamic lifestyle, where I also do research, serve my community, lead an organization, and teach the next generation.”

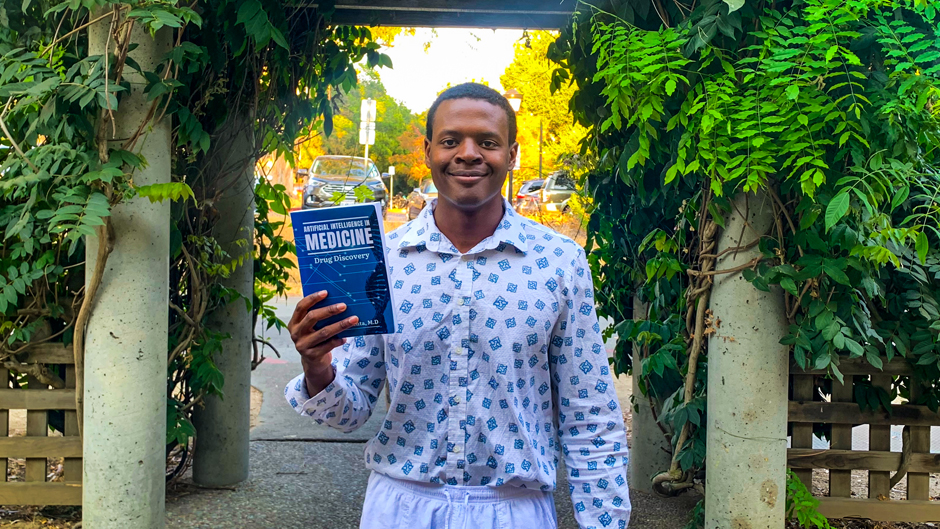

Some recent experiences also have helped Calixte solidify his interest in medicine. One of them is his work with the Lumen Foundation, an organization that aims to study the role of artificial intelligence in medicine. Calixte got involved with the organization before, but last year, he was asked to lead a team of international physicians, graduate students, and some pre-med classmates to research, write, and publish the medical textbook “Artificial Intelligence in Medicine: Drug Discovery.” It gives an overview of many AI tools being developed for the medical field to help drive down the cost of creating therapeutic drugs in the United States.

“Drug discovery is a lengthy and costly process that takes about 10 to 15 years on average and millions of dollars, with a low chance of making it to market,” Calixte said. “But AI could expedite that process to potentially get more therapeutic medicines on the market at a lower cost.”

Through his work on the book, Calixte said he was intrigued to learn about the drug discovery process because he knows that the costs of health care heavily impact communities of color.

“Driving down the cost of medicine in the U.S. is one of my ultimate goals,” Calixte said. “So, if AI can make the drug discovery process faster, it might alleviate that burden and help researchers uncover medications that could help more people recover quicker from illness.”

He is in the process of applying to medical school and plans to focus on cardiology, with an interest in underserved populations. Toward that goal, this summer he was able to join the DIVERSE Network Center, a research collaboration between Stanford University and Morehouse University’s medical schools, to improve minority representation in cardiology-related clinical trials.

Calixte’s interest in cardiology stems from his desire to help the largest number of patients possible. Since heart disease is the leading cause of death in the U.S., it also disproportionately affects underserved communities, Calixte pointed out. When he spent the summer after his first year working alongside Dr. Bernard Ashby at his outpatient cardiology clinic, Calixte got a firsthand view. One day, he noticed a female patient who was experiencing tremors and only spoke Haitian Creole, making it difficult for her to communicate with staff or to feel comfortable with them. However, Calixte grew up speaking the language with his parents and was able to calm her down and to draw her blood.

When she told him “medicine needs people like you,” Calixte said he realized the struggles that people from different cultures and languages experience in health care settings. And he hopes to change that.

Ayrimah Malcolm-Parker, a senior majoring in microbiology and immunology, worked closely with Calixte on the Lumen Foundation book and edited its chapters. She said Calixte was a great resource throughout the process; and as a result, the two ended up becoming friends. She even agreed to help with another University project that Calixte and another classmate started, called the 305 Give Back Drive. For the past two years, Miami natives Calixte and Ivette Acosta have used the campaign to collect school supplies for public schools in need.

“Jacques has a passion for community service that I’ve seen time and again, and I see him striving to resolve a lot of the inequity in local communities,” Malcolm-Parker said. “There’s a true passion for helping others and for helping people who may not be able to help themselves.”

He also has made an impression in his chemistry classes at the University. Lecturer Cesar Gonzalez was Calixte’s instructor in two courses and said he was always an active participant. Gonzalez noted that Calixte is able to seamlessly juggle his research and service activities and still earn high grades.

“Academically he did excellent work, but he was also always participating and asking questions, which showed me his interest in the topic,” Gonzalez said.