The latest consumer inflation report indicates that grocery prices have stabilized, yet the perception of high food costs lingers for many.

David Andolfatto, professor and chair of the University of Miami Patti and Allan Herbert Business School Economics Department, and David Kelly, economics professor and co-chair of the Sustainable Business Research Cluster, both recognize that supply and demand bottlenecks from the pandemic, high oil prices, wars, extreme weather, and crop disease all impact the massive movement of food goods around the world.

Kelly identified domestic factors affecting food prices—higher energy costs that impact transportation, fertilizer, and harvesting; extreme weather; regulations on trucking such as measures banning cages for chickens—yet emphasized that general inflation is far and away the major culprit.

“The vast majority of the high food prices are attributed to high inflation,” Kelly said. “Inflation certainly affects food as it does every other good. Since 2019, general prices have increased 4.2 percent per year, and food prices have risen 4.8 percent.”

Kelly qualified some media reports that food prices have risen steadily in recent decades.

“In fact, while the price of all goods has risen in past decades, food prices have risen less than most other goods,” said Kelly, citing data indicating that from 1952 to 2019 the price of all goods rose by 3.4 percent and increased 3.1 percent for food.

“The price of all goods goes up over time, and food is no exception,” added Kelly, who is also the academic director of the Master of Science in sustainable business. “We’ve had some great innovation in the food industry like seeds and the ‘Green Revolution’—the technology that’s utilized in food production now, such as farmers on their tractors using satellites to measure their watering needs. It’s gotten pretty high tech, and all those innovations are keeping food prices relatively low at a similar pace.”

Andolfatto disputed some media claims that grocery and restaurant food costs have risen continually in past decades and offered a different perspective for gauging the cost of food.

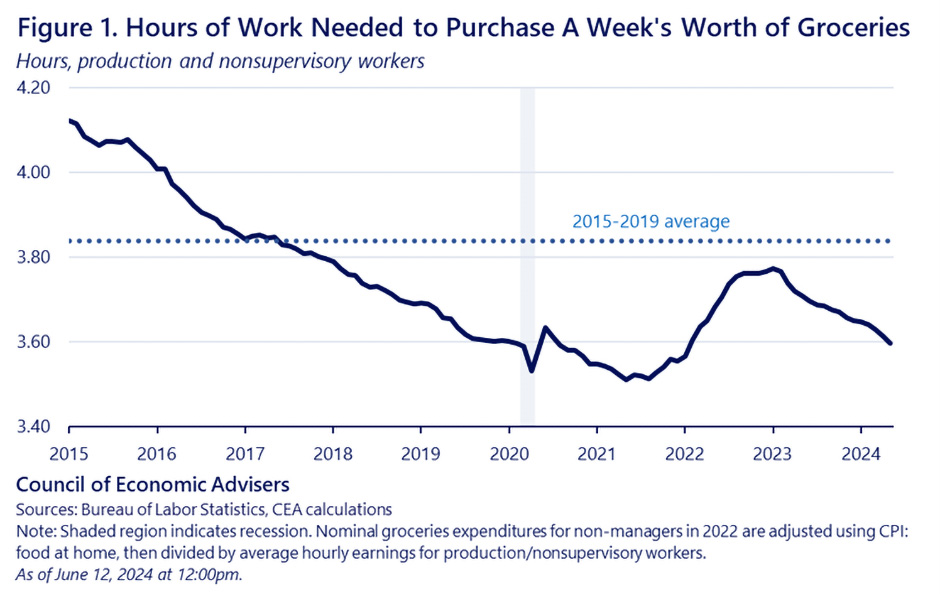

“It is my impression that the price of food in the long run has declined, say, when the cost is measured—as it should be—in terms of how hard one has to work to eat,” said Andolfatto. He cited a Council of Economic Advisers June 2024 graph that showed a steady decline since 2015 in the number of hours needed to work to purchase a week’s worth of groceries. The graph showed an upward spike during the pandemic.

Kelly noted the progress the Federal Reserve Board has made in terms of bringing down inflation but pointed to the budget deficit that has grown continually across recent administrations.

“The Fed needs some help from the fiscal side. Reducing spending is kind of a painful solution,” he said. Kelly suggested that looking for ways to increase the supply of food or to reduce regulations related to food production could help but said that gains in that direction would be minimal.

“You could do things such as reduce tariffs or promote free-trade agreements especially in agriculture, but those are not popular,” he said. “The government can do more research and development through the USDA (U.S. Department of Agriculture)—that’s a long-run strategy. Focusing on supply is good because it doesn’t restrict prices by taking money out of peoples’ pockets.

“The world demands a lot of food, and there are no free lunches in the economics of food,” Kelly said. “People may be willing to accept those trade-offs (such as the price increases that come from safe or environmentally friendlier production), but they just have to understand them better.”

Both economists emphasized that high food prices affect people in the low-income bracket the most.

“Lower-income quintiles spend proportionately more of their budget on food and shelter than higher-income quintiles. So, when food and shelter prices rise, the lower-income groups are hurt more,” said Andolfatto. He noted some of the programs in place designed to alleviate some of the hurt, such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, but said that, even when eligible, many people are not aware of the guidelines to access this aid.

“You have to go through lots of red tape, and it becomes tough to stay on top of all the different ways you can get food,” Kelly pointed out. “It’s not easy, even if you’re eligible, to keep on top of all the different programs.”