With the Eastern Seaboard in the bull’s eye of Hurricane Florence, storm experts at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science weigh in on the monster cyclone’s rapid intensification and what’s to come over the next few days.

How unusual of a storm is Florence?

Florence is rare in that it is so far north and still tracking westward. Usually, storms in the subtropics are influenced by mid-latitude troughs and “re-curve” northward then northeastward. The only other major hurricane I could find that passed within 200 miles of Florence’s current position and moved west was Dora (1964), which ended up hitting near St. Augustine, Florida.

—Brian McNoldy, senior research associate at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, who maintains a blog, Tropical Atlantic Update, and has been the tropical weather expert for The Washington Post’s Capital Weather Gang blog since 2012.

What can we expect from Florence over the next couple of days?

Over the next couple of days, Florence will experience some fluctuations in intensity due to subtle details in the environment and to internal processes called eyewall replacement cycles. It could swing into the Category 3 or 5 range, but should remain solidly at Category 4 status.

—McNoldy

Last week Florence weakened to a tropical storm and then regained strength. How unusual is that for a hurricane?

The abrupt weakening we saw last week was slightly out of the ordinary, but even a Category 4 hurricane could not hold up to extremely strong wind shear. It got its head knocked off! But, once it escaped that high wind shear zone, it rebuilt itself back up to a Category 4 hurricane. That roller coaster of intensity is certainly unusual.

—McNoldy

Will Florence’s speed decrease over the next 24 to 48 hours?

Florence is actually moving at a slightly faster-than-average speed: 16 miles per hour. But in two-to-four days it will find itself in a much weaker steering environment and could even stall over eastern South Carolina/North Carolina for several days. That would be disastrous as several feet of rain could accumulate there.

—McNoldy

What’s driving Florence’s rapid intensification?

Low atmospheric shear, well-defined inner core circulation, moist air, good exhaust fan on top of the hurricane, and a very warm ocean where ocean heat content values range between 75-00 kJ/cm-2, which means a deep, warm layer underneath a hurricane providing higher octane fuel to sustain the heat and moisture transfer from the ocean to the atmosphere. Note that a storm only needs 20-30 kJ/cm-2 ocean heat content (OHC) units to be maintained. Given these very favorable conditions, I do not see anything that will weaken this storm significantly. Keep in mind Florence still has to move over the Gulf Stream that will likely provide even more OHC prior to landfall.

—Lynn K. (Nick) Shay, professor in the Department of Ocean Sciences at the Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science

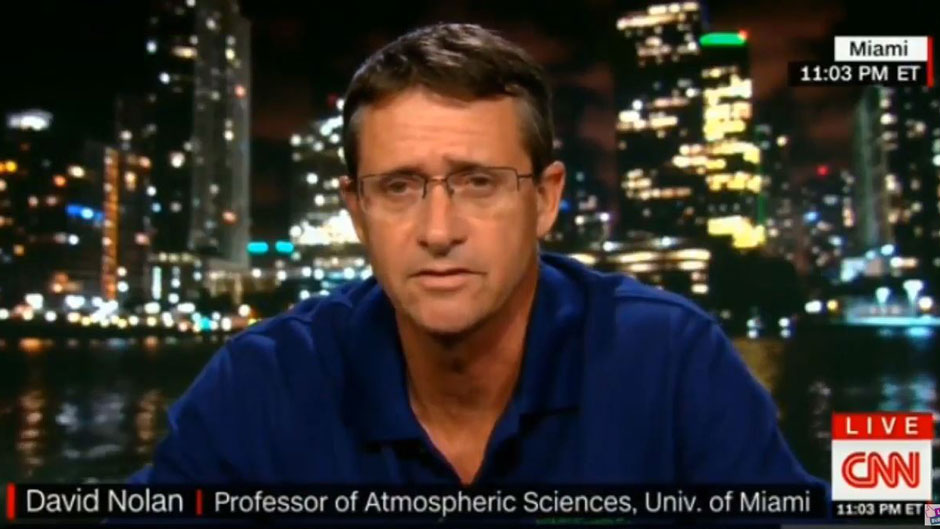

Florence is expected to hit the Southeastern Coast as a Category 4 or 5 hurricane, and there are other systems behind it. What’s driving this late-season flurry of storms, and what are the models telling us as far as Atlantic hurricane activity in the weeks to come?

Hurricane season peaks somewhere around September 7-12, so the recent activity is not unexpected, and having as many as three active hurricanes is also not that unusual. The unusual aspect, perhaps, is the strength and size of Florence. We have not seen a Cat-4 storm hit directly in the mid-Atlantic (perpendicular to the coast) since Hugo made landfall slightly north of Charleston, South Carolina on Sept. 22, 1989. The wind field associated with Florence is large—this increases the storm surge and coastal flooding. Florence is also forecasted to significantly slow and even linger once it makes landfall. This has the possibility of leading to substantial rainfall and associated inland flooding not too dissimilar to hurricane Harvey of last year.

The outlook, however, is for the risks of tropical cyclone development to return to more moderate levels for the week of September 12-18. In particular, there is a moderate risk of cyclone development in the Atlantic Ocean Main Development Region (MDR) and there is moderate risk in the western Gulf of Mexico. Beyond mid-September, the outlook is for a continued decline in the risk of tropical storm development as the warm El Niño conditions continue to develop on the Pacific.

—Ben Kirtman, professor of atmospheric sciences and director of NOAA’s Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies based at the Rosenstiel School.