As a super cyclone packing 150-mile-per-hour winds swirls in the Atlantic only a few hundred miles east of South Florida, residents with memories of the destruction wrought by monster storms like Andrew and Irma tune in to local broadcast stations and the Web for the latest storm updates, hanging on forecasters’ every word.

But what if the computer models used by those forecasters were unreliable? The time needed to prepare for the storm would be significantly reduced, putting lives and property in peril.

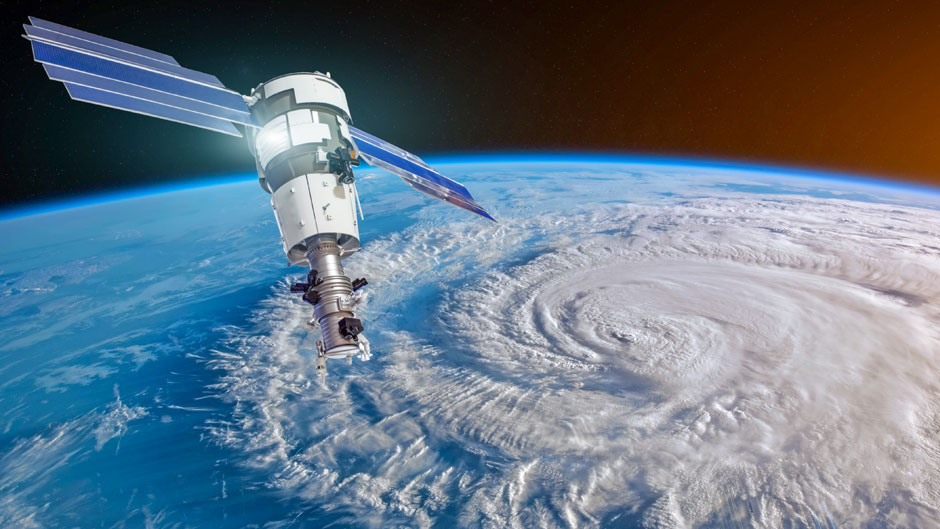

Some scientists fear that is what could happen when the fifth generation of cellular networks is rolled out across the U.S. While 5G will offer download speeds as much as 100 times faster than existing mobile networks, the technology, they say, interferes with critical satellite data used to help observe and forecast hurricanes.

Their primary concern is with the 24-gigahertz frequency the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) is using for 5G. The band is located in close proximity to one of the frequencies (22.235 gigahertz) emitted by the water vapor molecule, thought to be a critical component used to make accurate weather forecasts.

“Some weather satellites carry instruments that listen for faint signals around that frequency,” explained Brian McNoldy, a senior research associate at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science. “They are designed specifically to take advantage of this natural microwave emission to gather information about the vertical and horizontal distribution of water vapor in the atmosphere. There are also ‘wings’ around all of these values because neither transmitters nor receivers can operate at precisely a single frequency, so the 24 gigahertz signal being blasted from cell towers will easily interfere with or overwhelm the subtle 22 gigahertz signal coming from water vapor.”

And losing that vital water vapor data, he said, would be detrimental to forecast models. “Every global forecast model out there assimilates millions upon millions of data points at the beginning of each new cycle—every six or twelve hours—and a vast majority of those data points are collected by satellites,” he said. “Among those, measurements of water vapor are extremely valuable to a model’s performance, including those taken at the 22 gigahertz band.”

In a test that simulated interference, Superstorm Sandy, which struck the coasts of New York and New Jersey in 2012, killing dozens of people, was incorrectly forecast to head out to sea.

McNoldy noted that there are other water-vapor bands at other frequencies that would not be impacted by the 5G signal. “So all is not lost,” he explained. “But it’s certainly a handicap that partially offsets the gains made in modeling and computing power.”

Testifying before the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology last month, Neil Jacobs, acting administrator of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), said the interference could reduce forecast accuracy by 30 percent. “If you look back in time to see when our forecast skill was roughly 30 percent less than it was today, it’s somewhere around 1980,” he said.

In a blog post, Brad Gillen, the executive vice president of CTIA, the trade association representing the wireless communications industry in the U.S., blasted Jacobs’ statement, saying it is “an absurd claim with no science behind it” and that it is based on a study of a microwave sensor “that never went into use.”

Scientists have countered that Gillen is wrong, noting that a similar sensor is now deployed on at least two NOAA satellites.

With the FCC recently completing an auction of wireless spectrum in the 24-gigahertz range and with 5G phones already being rolled out in some markets, one UM researcher said “the jury is still out” on the degree to which 5G affects weather forecasting.

“If water vapor data is either removed or compromised, then that could degrade weather forecasts,” said Sharanya Majumdar, a professor of atmospheric sciences at the Rosenstiel School, whose research group uses several techniques to understand and improve the prediction of high-impact weather events, particularly tropical cyclones. “But the extent to which it is degraded is unknown. There are studies that are ongoing at NOAA and at NASA to quantify the impact of having this water-vapor channel compromised. But the results have not yet gone through the scientific scrutiny of peer review. There’s a fairly rigorous scientific process that’s needed before one can give any definitive commentary about the potential degradation of the data to forecasts.”