Over the next several days, scholars and researchers from the University of Miami, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Columbia University, Stanford University, the University of Pennsylvania, and other institutions will share their insights into the phenomena of extreme weather and explore ways to predict, respond to, and adapt to our changing climate.

News@TheU will provide continuous coverage. Check frequently for the latest news, photos, and more.

Friday morning: Researchers discuss wildfires in Florida and California

With temperatures rising across the planet due to global warming, wildfires will become more common in the future. At Friday’s final day of the Miami Climate Symposium, two scientists presented on the phenomenon of wildfires in two very divergent locations—Florida and California.

With temperatures rising across the planet due to global warming, wildfires will become more common in the future. At Friday’s final day of the Miami Climate Symposium, two scientists presented on the phenomenon of wildfires in two very divergent locations—Florida and California.

Chris Holmes, an assistant professor of atmospheric science at Florida State University, has studied wildfires extensively and determined that most of the fires throughout the nation happen in the southeastern United States. However, most of the fires that occur are prescribed burns, done as a preventative forestry measure to protect land and wildlife, he said. In Florida alone, there are 25,000 fires burning each year, Holmes added, yet only 8 percent of them are wildfires. This has helped the state to prevent more wildfires for many years.

“Overall, we’ve got 7 percent of land burning in Florida each year, but it appears that this strategy [of prescribed burns] reduces the risk of wildfires in Florida each year,” he said.

With climate change bringing more rain and hotter temperatures, Florida forestry officials will need to find enough days with safe conditions for doing controlled burns. “The key climate challenge for fire managers will be gathering a greater amount of resources with a greater capacity for a longer season to manage prescribed fires,” he said.

California experiences only about 8,000 wildfires a year, but those fires are much larger in scope and therefore require lots of planning so that people are no longer in danger, said Rebecca Miller, a Ph.D. student at Stanford University. An outbreak of wildfires in 2017 and 2018 burned 3 percent of the state and were the most devastating fires on record for California, she added. There were more structures destroyed and lives lost as a result of fire than in the 17 years before.

That’s why for her research, Miller decided to interview 140 first responders and local officials involved in those fires. She learned that some communities, such as Sonoma County and the City of Mill Valley, just north of San Francisco, have developed disaster response plans in recent years that will protect their residents and property for the inevitable future emergencies. “Every phase of disaster cycle is an opportunity for policy intervention, and adaptation,” she said. “Sonoma County had a catastrophic series of fires, and it’s exciting to see these changes happening now.”

Miller said just weeks after the area had undergone flood response training, Sonoma County had their first flood in years, and in 2019, when the area had another wildfire, evacuations went smoother. “Today, when there’s a red flag warning [that fire conditions are present], people know what that is,” she said. “And when the Kincade fire of October 2019 happened, firefighters said it was night and day—192,000 people were evacuated in five hours—even though it was largest fire in Sonoma’s history. It’s an indication of what can happen when you put money, power and action behind resiliency planning.”

--- Janette Neuwahl Tannen

Friday morning: Florida Power & Light investing in a smarter, stronger grid system

After a blitz of hurricanes struck Florida in 2004 and 2005, Florida Power & Light instituted a “storm secure program” to update its systems, strengthen infrastructure, and take a proactive approach in other areas to protect the utility’s assets and grids, said Michael Jarro, vice president for transmission and substation for FPL. Workers installed stronger utility poles, and added more poles to shorten the span of wires. Flood monitoring devices were installed in more than 225 substations, giving workers advance notice when a substation may be threatened by rising waters. More than 15,000 miles of power lines are trimmed of vegetation yearly, and the company is inspecting 150,000 utility poles annually.

After a blitz of hurricanes struck Florida in 2004 and 2005, Florida Power & Light instituted a “storm secure program” to update its systems, strengthen infrastructure, and take a proactive approach in other areas to protect the utility’s assets and grids, said Michael Jarro, vice president for transmission and substation for FPL. Workers installed stronger utility poles, and added more poles to shorten the span of wires. Flood monitoring devices were installed in more than 225 substations, giving workers advance notice when a substation may be threatened by rising waters. More than 15,000 miles of power lines are trimmed of vegetation yearly, and the company is inspecting 150,000 utility poles annually.

FPL operates in 35 counties in Florida, boasts 1.2 million poles and structures in its system, operates 75,000 miles of power lines, and serves 5 million customers—a majority of whom live within 20 miles of coastlines. The company must protect its assets from thunderstorms, flood risks, extreme temperatures, salt spray, and motorists crashing into poles and causing isolated outages, Jarro said.

But the biggest threat, Jarro noted, is hurricanes. Florida, he added, has experienced 140 hurricane landfalls from 1851 to 2018. The company, he said, finds itself constantly “either preparing for a storm, or in the midst of [cleaning up and restoring power] after a storm.” In addition to protecting its assets and grids, the company is also using drones to inspect the grids and improve preventative maintenance.

“We have made a significant level of investment in technology,” said Jarro, an alumnus of the University of Miami. FPL is a sponsor of the Miami Climate Symposium 2020, presented by the University of Miami.

--- Peter E. Howard

Friday morning: Winter forecasts are hard to predict due to competing atmospheric factors

Polar vortex. Before the winter of 2013 and 2014, that was not a common term. But the frigid temperatures and snowstorms of that winter resulted in meteorologists and journalists having to repeat the word over and over. It also prompted meteorologists to scratch their heads because it was unexpected, at least according to forecast models.

Polar vortex. Before the winter of 2013 and 2014, that was not a common term. But the frigid temperatures and snowstorms of that winter resulted in meteorologists and journalists having to repeat the word over and over. It also prompted meteorologists to scratch their heads because it was unexpected, at least according to forecast models.

“Because that winter was so severe it attracted a lot of attention from the research community,” said Peitao Peng, a meteorologist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Climate Prediction Center in Maryland. He believes that anomaly of a winter, and U.S. models’ inability to forecast it, lies in the difficulty of predicting tropical sea surface temperatures, which are often a precursor to strong winters. That extreme 2013 winter, he said, was likely an oceanic response to a pattern that arrived in the atmosphere in December, called a “wave train” that stuck around until March of 2014.

It is difficult to offer a nuanced forecast of the winter because this atmospheric pattern depends on the sea level pressure in the North Pacific and is highly variable, Peng pointed out. In order to better predict winter conditions, he added, we need to be able to forecast tropical sea surface temperatures better.

--- Janette Neuwahl Tannen

Friday morning: Can a multi-model ensemble predict extreme seasonal temperatures?

With extreme heat and cold events now part of the new normal of Earth’s climate present and future, forecasters increasingly want to know if the current suite of climate models is effective at predicting seasonal temperatures.

With extreme heat and cold events now part of the new normal of Earth’s climate present and future, forecasters increasingly want to know if the current suite of climate models is effective at predicting seasonal temperatures.

That’s the topic Emily Becker, an associate scientist at the Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, addressed in her presentation at the Miami Climate Symposium, as the final day of the summit continued with discussions primarily centering around heat waves, cold spells, and fires.

Becker, who specializes in sub-seasonal and seasonal climate prediction and predictability, specifically focused on whether the North American Multi-Model Ensemble (NMME) can effectively predict extreme seasonal temperatures.NMME is a seasonal forecasting system that consists of several different models from a conglomerate of North American modeling centers, such as NOAA, NASA, Environment and Climate Change Canada, the National Center for Atmospheric Research, and others. Ben Kirtman, Rosenstiel School professor of atmospheric sciences, helped develop the model.

“What we have found through extensive experimentation is that when you take a few different models and combine them, you get better results,” said Becker. “And that’s because all models aren’t perfect; they have biases. But when you combine them, those biases are eliminated.”

So just how good is the system at predicting seasonal temperature extremes? Here’s some of what she found:

• The system has proved effective at predicting warm extremes in some locations and predicting cooler extremes in other areas.

• Predictions of seasonal temperature extremes are improving.

• In real time NMME, cold anomalies have been more difficult to forecast than warm.

Becker called the NMME an unprecedented system, noting that it follows strict protocols and produces data that are available to the public. Several groups, including the U.S. Air Force, now use the NMME, which went operational in 2011.

--- Robert C. Jones Jr.

Friday morning: Scientist analyzes heat waves in the US

Hosmay Lopez, with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, spends much of his time analyzing data that helps him predict and understand how heat waves form, and where they will hit in the United States. He and his team of scientists zeroed in on four regions in the U.S.—the Great Lakes, western U.S., Great Plains, and southern regions—showing that climate change will have an impact on patterns and intensity during the next several decades.

Hosmay Lopez, with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, spends much of his time analyzing data that helps him predict and understand how heat waves form, and where they will hit in the United States. He and his team of scientists zeroed in on four regions in the U.S.—the Great Lakes, western U.S., Great Plains, and southern regions—showing that climate change will have an impact on patterns and intensity during the next several decades.

Heat waves, he said, are responsible for the most weather-related deaths in the U.S. The two most recent severe events occurred in the Great Plains in 2011, when 206 people died, and in 2012, with 155 deaths. During 2011, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, recorded 40 days with temperatures exceeding 100 degrees. In 2012, Dodge City, Kansas, recorded a record 111-degree day during the heat wave.

Lopez, who earned his doctoral degree in meteorology and physical oceanography at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, opened the final day of the Miami Climate Symposium, which is being presented by the University of Miami. He said the goal of his team's research is to develop a prediction system for heat waves and droughts. One of their findings show that the East Asian Monsoon, which grabs its moisture from the Indian and Pacific oceans, can be a predictor of the occurrence and frequency of heat waves in the Great Plains area.

--- Robert C. Jones Jr. and Peter E. Howard

THURSDAY, JAN. 23

Thursday afternoon: Miami-Dade County focused on preparing for sea level rise

A recent headline in the Miami Herald read: As seas rise, your coastal home in Florida could lose value. One report says 15 percent by 2030.

A recent headline in the Miami Herald read: As seas rise, your coastal home in Florida could lose value. One report says 15 percent by 2030.

“We wake up to these headlines everyday. These are the ones that scare fiscal managers,” Jim Murley, Miami-Dade County’s chief resilience officer, said Thursday at the Miami Climate Symposium. But as alarming as such headlines are, Murley has found solace in knowing that the county he serves—an area about the size of Rhode Island that is inhabited by some 2.8 million people—is preparing for the effects of climate change, most notably sea level rise. He outlined some of those preparation measures during his presentation Integrating Regional and Local Actions to Address Short and Long-Term Coastal Flooding.

Working with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is critical, he said. As such, the county is partnering with the corps on a new study that examines storm surge, evaluating the tsunami-like phenomenon of rising water from different angles, including the installation of floodwalls and how they could be effective in protecting urban areas. He touted the county’s relationship with the federal government in addressing the issue and noted that Florida Governor Ron DeSantis has appointed the state’s first chief resilience officer, Julia Nesheiwat. “So we’re getting attention in that area,” Murley said.

Water, and the management of it, will always be an issue, he explained, noting that some areas in the county are now faced with the problem of not being able to drain water after heavy rainfalls. He detailed Miami-Dade’s working relationship with other counties on the regional level, from Broward and Palm Beach to Monroe, saying such partnerships will help increase knowledge and observations of sea level rise. He said Miami-Dade is looking at transects across the entire county. “It starts out in the ocean where the reefs are because they’re part of our coastal management system.”

And he asked the auditorium full of researchers to continue using their qualitative knowledge to help Miami-Dade move forward over the next five years. “We have to continue to push ourselves on mitigation, not just adaptation,” Murley said.

--- Robert C. Jones Jr.

Thursday afternoon: Climate adaptation is a hyper-local issue

A round of lightning talks concluded with Gina Maranto, co-director of the undergraduate program in ecosystem science and policy at the University of Miami’s Abess Center, presenting on her team's U-LINK Hyper-localism: Transforming the Paradigm for Climate Adaptation project.

Recognizing that the impact of climate change will differ from neighborhood to neighborhood, members of the team are exploring hyper-local, rather than regional, adaptations that will allow neighborhoods and communities to tailor effective climate action plans for their unique circumstances.

Their goal is to move the conversation about climate change to a “people-first perspective” and, to that end, members are developing an Integrated Climate Risk Assessment protocol with community partners, including the CLEO Institute, Catalyst Miami, and The Nature Conservancy, to close the gap between top-down policies and neighborhood interests. The researchers recently received a $50,000 grant from AT&T that will help them advance their work.

Other Hy-Lo team members include Joanna Lombard, professor in the School of Architecture and Department of Public Health Sciences at the Miller School of Medicine; Tyler Harrison, professor in the School of Communication; Sam Purkis, professor and chair of marine geosciences at the Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science; and Angela Clark-Hughes, director of the Rosenstiel School library.

--- Robert C. Jones Jr.

Thursday afternoon: Law students advocate for legislation to protect renters from flood risks

Whether due to sea level rise, king tides, or torrential summer thunderstorms, many areas in South Florida battle flooding time and again. While home buyers are told about a property’s flood risk, there is no Florida law that requires a property’s owner to notify renters that the house or apartment they want to lease is prone to flooding.

Whether due to sea level rise, king tides, or torrential summer thunderstorms, many areas in South Florida battle flooding time and again. While home buyers are told about a property’s flood risk, there is no Florida law that requires a property’s owner to notify renters that the house or apartment they want to lease is prone to flooding.

That means renters often face unfortunate surprises, according to University of Miami law students Bethany Blakeman and Gabriela Falla.

“Under Florida law, landlords are not required to disclose a property’s flood risk,” Falla said. “But we believe homeowners and renters should make an informed decision about where they want to live.”

As part of their work with the Environmental Justice Clinic at the School of Law, Blakeman and Falla are comparing Florida laws about the issue with legislation in other states. Both students said they were surprised to learn that Florida law lags behind many of its coastal neighbor states that experience some of the same climate-related risks. The students are advocating for state and local officials to pass laws that will provide potential renters and home buyers with more information about flooding. After Hurricane Harvey dumped a record 60 inches of rain on the Houston area, Texas passed strict laws about flood risks.

“In Florida, we don’t want to implement something as a reactionary policy, we should instead take proactive steps to protect people before the inevitable Category 5 storm puts people in harm’s way,” Blakeman said. “The time is now for Florida to enact common-sense policy by passing mandatory flood response disclosures.”

--- Janette Neuwahl Tannen

Thursday afternoon: Abess Center honors three resiliency officers

A trio of local resiliency officers received the University of Miami Leonard and Jayne Abess Center for Ecosystem Science and Policy’s Reitmeister Award at the Miami Climate Symposium on Thursday.

A trio of local resiliency officers received the University of Miami Leonard and Jayne Abess Center for Ecosystem Science and Policy’s Reitmeister Award at the Miami Climate Symposium on Thursday.

The award, named for Louis Aaron Reitmeister, a 20th century American writer whose dedication to both humanism and the environment was a life-long commitment, recognizes individuals who have made significant contributions to conservation in Florida.

The recipient of the award were:

Jane Gilbert, the City of Miami’s first chief resilience officer, who leads Miami’s resilience strategy development and works in partnership with the City of Miami Beach and Miami-Dade County to develop the region’s first comprehensive Resilience Strategy Plan for Greater Miami and the Beaches. Additionally, as director of the city’s Office of Resilience and Sustainability, Gilbert is charged with leading the city’s response to the impacts of climate hazards.

Jim Murley serves has chief resilience officer for Miami-Dade County. In this role he leads the seventh-largest county in the United States in sustainability and resilience issues. He heads the Office of Resilience, which focuses on energy efficiency and conservation actions, and addresses the impacts of sea level rise. Miami-Dade County joined with the cities of Miami and Miami Beach to form the Greater Miami and the Beaches Partnership as a part of 100 Resilient Cities, a program funded by the Rockefeller Foundation.

Susy Torriente joined the City of Miami Beach in September 2015 as assistant city manager and chief resiliency officer. Her sustainability and resiliency portfolio includes planning, building, code compliance, green space, and environmental management. As chief resiliency officer she is building a foundation to develop an action-oriented citywide strategic resiliency plan for all city operations.

--- Robert C. Jones Jr.

Thursday afternoon: Researcher lists the pros and cons of managed retreat due to climate

In some cases it has been unavoidable, the result of a disaster like a cyclone. In others, it has been voluntary.

In some cases it has been unavoidable, the result of a disaster like a cyclone. In others, it has been voluntary.

But whichever the case, managed retreat—moving people and property out of harm’s way from climate-related consequences such as sea level rise—can be efficient and effective if the people being relocated are going to a safer place.

That was one of the statements made by Katharine Mach, an associate professor of marine ecosystems and society at the University of Miami, during her presentation on Managed Retreat as an Adaptive Response to Climate Change at the Miami Climate Symposium on Thursday.

Mach has been on the front lines of the climate emergency issue even before she came to the Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science in August. As a researcher at Stanford University and also as co-director of scientific activities for Working Group II of the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), she has focused on the risks of a changing climate, how society is managing those risks, and the role of academic research in that landscape.

At the IPCC, her work culminated in the panel's Fifth Assessment Report as well as its Special Report on Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation. Mach's scientific group has analyzed more than two-dozen cases of managed retreat across different countries. “Over 1 million people have moved globally because of the risks of climate change,” she said.

In most managed retreat cases in the U.S., this takes the form of local and state governments buying residents out of their property, which is typically located in a flood zone. Although this can be unpopular, Mach said, it is happening across the world today from Alaska to the Netherlands to Staten Island, N.Y.

Her research on managed retreat in the U.S. garnered national headlines this past summer. In one study—which was published in the journal Sciences Advances and for which Mach served as the lead investigator—she discovered that a government buyout program designed to help U.S. residents move out of at-risk areas actually benefits more wealthy municipalities.

Specifically, she and her team of researchers found that local governments are using FEMA funds to purchase flood-prone homes more often in affluent counties than in poorer ones. This is most likely because buyouts that require enormous resources to administer, higher-capacity locations—as measured by income—have been more likely to get FEMA funding to do buyouts. Since 1989, Mach said buyouts have occurred in more than 1,000 counties in 49 states. The government started buying homes along the Mississippi River with an uptick in recent years across coastal areas of the U.S.

Despite its sometimes-controversial nature, there are benefits to managed retreat, Mach added. “From a cost perspective, it’s beneficial,” she explained. “It’s also a safer measure because you’re not exposing people to flooding anymore. And, if done well, retreat can help maintain biodiversity, too.”

--- Janette Neuwahl Tannen and Robert C. Jones Jr.

Thursday morning: Symposium helps students delve further into their research

Carolien Kraan, a Ph.D. candidate in the Abess Center for Ecosystem Science and policy at the University of Miami, is working on a dissertation about coastal flooding and how society keeps residents safe from rising sea levels. Kraan said she has listened eagerly and attentively throughout the symposium and is fascinated by what she has learned about the effects of global warming.

“I have enjoyed learning about the physical science of climate change and how hard it is to predict future tropical cyclones, and the floods of the future,” she said. “I'm excited to learn more about resilience during this afternoon’s sessions.”

Lamis Amer, a Ph.D. candidate studying industrial engineering at the University, is interested in doing her dissertation on a climate change topic. Amer said she enjoyed the presentations by Key Biscayne officials yesterday, as well as Jen Posner's session this morning on housing resiliency, because they covered the actions that cities are taking to address rising sea levels.

“The Miami Housing Solutions lab [at the University of Miami] showed what housing should look like in the future,” Amer said. “That was helpful because I will be looking into planning and risk management, and what needs to be done and in what order [to protect cities from the impacts of climate change].”

--- Janette Neuwahl Tannen

Thursday morning: Housing resiliency and a sustainable South Florida

With recent studies labeling Miami as one of the least-affordable places in the world to live, the impact of sea level rise and climate change on the city’s housing market has further compounded a problem for a segment of the population struggling to pay.

With recent studies labeling Miami as one of the least-affordable places in the world to live, the impact of sea level rise and climate change on the city’s housing market has further compounded a problem for a segment of the population struggling to pay.

“We’ve slowly been seeing the impact of climate change and how it can exacerbate housing affordability,” said Jen Posner of the University of Miami’s Office of Civic and Community Engagement (CCE), which, since its start in 2011, has addressed the issue of affordable housing head on—creating a suite of publicly assessable mapping tools that address the issue.

During her lightning talk at the Miami Climate Symposium, Posner detailed many of those tools for climate researchers, including the interactive Land Access for Neighborhood Development, or LAND, mapping tool. It provides a snapshot of the location, size, and ownership of publicly- or institutionally-owned lots that could be assembled across jurisdictions and along transportation hubs to house low- and middle-income residents.

Noting that the Miami metropolitan area is high on the list of residents who are spending more than 50 percent of their income on housing and transportation, Posner said her office is now studying climate change and resiliency indicators in relation to Miami’s affordable housing stock.

CCE, she said, has plans to expand its Miami housing policy toolkit to look at best practices and regulatory policy changes, helping area advocates and leaders who want to make housing more affordable.

--- Robert C. Jones Jr.

Thursday morning: Reynolds is committed to meeting ‘the challenge of a generation’

Delaney Reynolds speaks with all the passion of environmentalist Greta Thunberg, telling people whenever she can that climate change is the “most significant challenge” her generation will ever face.

Delaney Reynolds speaks with all the passion of environmentalist Greta Thunberg, telling people whenever she can that climate change is the “most significant challenge” her generation will ever face.

“What we do to solve it will define our time on Earth,” said the 20-year-old, a marine science and coastal geology major at the University of Miami. During her 10-minute lightning talk at the Miami Climate Symposium, Reynolds, using powerful vignettes, outlined the challenge her generation faces.“Young people are concerned and value the science and what you’ve been doing,” she said to an audience of climate researchers. “That’s what I’ve seen and heard with my own eyes and ears.”

Reynolds grew up near Matheson Hammock Park on Old Cutler Road in Miami, learning how to swim at the 630-acre site. But, a roadway near that park has been wiped out by sea level rise and Hurricane Irma.“We’re seeing about six to eight days of sunny-day flooding,” she lamented. And by the year 2030, she added, Miami could be experiencing more than 300 flooding events a year.

Having published three children’s books on climate change, Reynolds now is writing a fourth on sea level rise. She’s interviewed scientists, learning from them how they’ve been impacted by climate change and what they’re doing about the problem. One of those scientists is Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science researcher Ben Kirtman, one of the organizers of the three-day symposium.

“He provided me with inspiration,” said Reynolds, who said Kirtman told her that climate change poses a grave threat to polar bears in the Arctic. That statement stuck with her, inspiring her to produce a comic book, “Where Did the Polar Bears Go.”

She founded the Sink or Swim initiative to educate people and raise awareness about climate change. “My goal is to educate as many people as possible, especially children,” Reynolds said. She wants to see a deeper commitment to curtailing the use of fossil fuels, and more use of alternatives such as solar power are needed.

“We’re running out of time and have to do everything possible instead of watching our planet burn and die,” said Reynolds.

--- Robert C. Jones Jr.

Thursday morning: Measuring sea level rise in your backyard

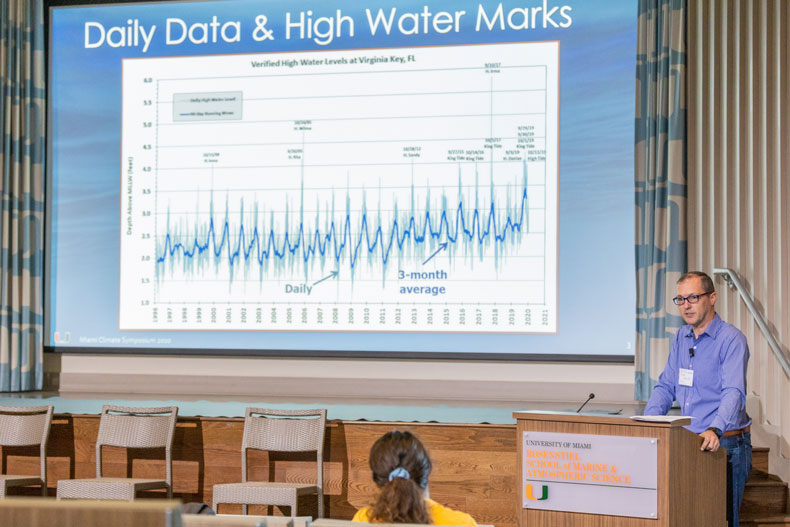

University of Miami senior research associate Brian McNoldy, who is also a tropical cyclone expert, shared sea level data collected at the Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science over the past three decades. "Sea level has risen 5.7 inches in the past 26 years, which is fairly significant,” he said. “We used to only see these types of water events from hurricanes or king tides.”

University of Miami senior research associate Brian McNoldy, who is also a tropical cyclone expert, shared sea level data collected at the Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science over the past three decades. "Sea level has risen 5.7 inches in the past 26 years, which is fairly significant,” he said. “We used to only see these types of water events from hurricanes or king tides.”

McNoldy said that sea level is affected by tides as well, and this morning's 8 a.m. reading was the highest tide recorded for Jan. 23 at the University's marine campus, which is located on Virginia Key in Biscayne Bay.

--- Janette Neuwahl Tannen

Thursday morning: Professor focused on improving flooding forecast models

In the not-so-distant future, the local news forecast may look very different in Miami, said Ben Kirtman, professor of atmospheric science at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science. Instead of hearing about the weather, it may turn into a future flood outlook.

In the not-so-distant future, the local news forecast may look very different in Miami, said Ben Kirtman, professor of atmospheric science at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science. Instead of hearing about the weather, it may turn into a future flood outlook.

“Every single time I go to give a talk, people ask me 'how many times is it going to flood on my street?'” said Kirtman, who is also director of the Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies. But making that forecast is very tricky, he said. That is why he is working to create a more reliable model.

One of Kirtman’s graduate students has been able to nail down some of the main factors affecting sea level rise, which is accelerating at a faster rate than scientists predicted. Vertical land movement, ocean circulation, the ocean’s melting and thermal expansion—also known as a warming planet—all affect sea levels, he said. One thing the public must understand about these factors is that sea level rise is caused by humans, he added. Data shows that sea levels remained stable until 1900, when industrialization began.“Sea level has definitively risen due to human activity,” he noted.

However, incorporating all those factors into an accurate forecast model is complicated, he said. Kirtman and his team of graduate students continue to work on a new model and are getting closer all the time. Their hope is to eventually provide a detailed street-by-street forecast, although, he admits that this is still a lofty goal.

“I can dig in and start to take sea level pressure, winds, sea surface height, and start to make a prediction about flooding risk,” he said. “This problem is hard, and expensive to do computationally, but it will make my forecast credible and better.”

--- Janette Neuwahl Tannen

Thursday morning: Marine scientist uses intricate graphs and statistics to prove the sea level rise phenomenon

Gary Mitchum has no patience for the naysayers: people who refuse to believe that climate change is real and that sea levels are rising.

Gary Mitchum has no patience for the naysayers: people who refuse to believe that climate change is real and that sea levels are rising.

Those doubters need only examine evidence—data and intricate graphs and statistics—that Mitchum, a professor of marine science at the University of South Florida, has compiled over the years showing the undeniable truth that sea levels are, in fact, increasing. On Thursday, as the Miami Climate Symposium entered its second day at the University of Miami, Mitchum presented a powerful case to bolster what he and other scientists have long known.

“Where I live in Tampa Bay, we’ve been tiptoeing around the idea of mitigation,” Mitchum said during his presentation—Sea Level Rise, Climate Sensitivity, and Ocean-Atmosphere Variability: An Evolving Landscape. “But that’s all we need to be talking about now.”

Mitchum presented a series of graphs and charts showing a steady rise of sea levels in the St. Petersburg/Tampa area on Florida’s west coast. “The key point is we know what we need to know about flooding events and how to predict them,” he said. “But the challenge we face is that everything that goes into this is evolving.”

The marine scientist and a former graduate assistant have used data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to construct a graph showing intermediate lows and highs for sea level rise projections. They’ve also analyzed satellite data, refuting one model, what he called a North Carolina curve, that showed hardly any increase in seal level rise.

“If you look at long sea level rise projections, we see a constant rate of rise and then it jumps,” Mitchum said.

One challenge that remains: Getting people to accept the hard truth. “When you’re talking to the public and a lot of elected officials, there’s a disconnect that happens,” said Mitchum, explaining that he always shows people the curve that shows a marked increase in rising sea levels.“That disconnect is something we’re not doing a good job in communicating,” he said.

--- Robert C. Jones Jr.

WEDNESDAY, JAN. 22

Wednesday afternoon: Predicting atmospheric rivers and precipitation

Her primary research interests focus on the variability of the atmosphere to better interpret and predict its behavior over a range of timescales and climates.

Her primary research interests focus on the variability of the atmosphere to better interpret and predict its behavior over a range of timescales and climates.

Libby Barnes, associate professor in the Department of Atmospheric Science at Colorado State University, uses a range of tools to perform that task, looking at everything from precipitation patterns to hail and even tornado activity.

“If I’m in Seattle, can I expect more storms and atmospheric rivers,” she said during her Miami Climate Symposium presentation, “Empirical Models for Predicting Atmospheric Rivers and Precipitation.”

Barnes noted that some models are going beyond what our weather models can do, typically by two to three weeks. But sometimes data can be flawed. The solution? “Let’s learn from imperfect data, refine it with observation, and output a prediction model that’s better,” she said.

She left the audience with one particular question to ponder for the future: While modelers may have the skill now, will those models be as effective in making predictions decades from now?

--- Robert C. Jones Jr.

Wednesday afternoon: Using climate models to predict extreme rainfall

Record rains in Fort Lauderdale in December? Can it be?

Record rains in Fort Lauderdale in December? Can it be?

If you’re a resident of Broward County or caught any part of a South Florida local television weather report that aired on Dec. 23, you’d know that the answer is yes. That’s the date on which the National Weather Service confirmed that rainfall, as measured at Fort Lauderdale-Hollywood International Airport, broke a near 80-year-old record by more than five inches. So it seemed only fitting that extreme rainfall was a hot topic of discussion at an afternoon session of the Miami Climate Symposium.

“Can we predict how much extreme rainfall will change, and can we use it for resiliency planning purposes?” Jayantha Obeysekera, director and research professor in the Sea Level Solutions Center at Florida International University, asked the audience when opening his talk, “Challenges in Predicting Extreme Rainfall Using Statistical and Dynamical Downscaling.”

Obeysekera, who is the chief modeler at the South Florida Water Management District, said the impacts of climate change, storm surge, and sea level rise seem worse in Florida, and emergency managers continually want to know if we’ll see more extreme rainfall events in the Sunshine State in the future. The problem is, he said, “we don’t have a good handle on rainfall patterns of the future.”

But here is what is known about the current state of modeling for extreme rainfall:

• While they are not generally designed for extreme rainfall, dynamical downscaled data performs better in such predictions.

• Hybrid downscaling using high-resolution Weather Research and Forecasting models appears to be promising.

• Existing regional climate models may not have the resolution necessary to predict effects local meso-scale phenomena and teleconnections. A more reliable tool is necessary to explore simulation experiments to answer key answers that would influence resiliency planning.

--- Robert C. Jones Jr.

Wednesday afternoon: The role corals play in wave mitigation, coastal protection The battle to protect Florida’s coastline from decay triggered by climate extremes has started in a research lab at the University of Miami.

The battle to protect Florida’s coastline from decay triggered by climate extremes has started in a research lab at the University of Miami.

There, coral reef expert Diego Lirman and his colleagues are building hybrid structures—nursery-grown corals—that will eventually be transplanted off the coasts of Miami-Dade and Broward counties, where coral colonies have suffered significant losses.

“These natural ecosystems [coral reefs] are the first defenses against climate extremes,” Lirman, a professor at the University's Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, said Wednesday afternoon during one of the Miami Climate Symposium’s Lightning Talks in which researchers address a critical issue in 10 minutes or less.

But tragically, these natural defenses are under assault as climate change has reduced their effectiveness from 40 percent stony coral cover to less than 5 percent.

“We’ve lost a tremendous amount of structure that protects our shoreline,” he said. And it’s not just corals. Mangroves and seagrasses are only a fraction of what they once were, he said, adding, "when we lose structure, we lose protection.” More people get displaced, more areas flood, and resources are depleted, Lirman warned.

This is where an innovative project in which Lirman is a team member comes to light.

He and a group of researchers are investigating how corals, and their hybrid stand-ins, can protect the coastline of the Sunshine State as part of a University Laboratory for Integrative Knowledge (U-LINK) project at the University of Miami.

Professors Andrew Baker and Brian Haus from the Rosenstiel School, along with professor Landolf Rhode-Barbarigos from the University’s College of Engineering are the other team members. The group recently received a $3 million grant from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation’s coastal resilience fund, and the University, along with numerous local, state, and corporate partners, are matching the funding, for a total of $6 million devoted to the project.

The team, Lirman told the audience at the symposium, has already tested the hybrid structures in the Rosenstiel School SUSTAIN lab, and they are set to deploy the first test structures off the coast of Miami Beach, going from the tank to the shoreline “to see if these hybrids can do what they’re supposed to do,” he said.

Lirman said the team has already had “very promising results” in the lab. “We want these coral protecting our shoreline,” he said.

--- Robert C. Jones Jr.

Wednesday afternoon: Power grids at risk and sea wall alternatives

Udayan Singh, a doctoral student researching engineering systems and the environment from the University of Virginia, explained his research about how to prepare U.S. electrical grids for future effects of climate change. Singh said that coastal states such as California, Florida, Virginia, and Texas are most at risk. He stressed the need for diversity, redundance, flexibility, and a decentralization of power plants in order to overcome the inevitable impacts of sea level rise, storms, and other extreme weather events that may occur due to climate change.

“It makes economic sense to build large power plants, but at the same time there’s economic value to having resilience in our system and that’s what we should try to do now,” he said. “The power plant of the future would be able to use different sources of electricity.”

Landolf Rhode-Barbarigos, professor in the University of Miami College of Engineering, discussed his environmentally-friendly design to replace traditional seawalls, which are unable to withstand rising sea levels and are deteriorating across the coast. “The number of disasters has been increasing in last 40 years, so now we have more disasters creating more damage,” he said. “The southeastern U.S. is more prone to these disasters, so we want to make our coastal communities less prone to coastal damage.”

To combat this and offer a manmade “gray” solution, Rhode-Barbarigos developed the SEAHIVE, a hexagonal, perforated column that will allow wave energy to pass through it, but will also slow wave energy and work to protect the coastline like coral reefs do.

“You can use the SEAHIVE horizontally or vertically, and it can be cost-effective,” said Rhode-Barbarigos, who is also part of a University Laboratory for Integrative Knowledge (U-LINK) team on coastal resilience. “You can use traditional pipemaking equipment to create the SEAHIVE and can use concrete made of seawater, and noncorrosive rebars.”

He currently is testing his innovation at the Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science with the help of professor Brian Haus, a coastal engineer who is also chair of the Department of Ocean Sciences.

Soon, Rhode-Barbarigos will be testing his design in North Bay Village, a city built at sea level in the middle of Biscayne Bay.

--- Janette Neuwahl Tannen

Wednesday morning: A lightning round of comments on climate and weather

Nick Shay, professor of oceanography in the Ocean Sciences Department at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, has developed the Southeast Coastal Ocean Observing Regional Association, a nonprofit organization that works to track data on the oceans. As a result of the organization’s funding, Shay has put in place a network of 13 ocean radars off the Florida coastline to track data on the ocean and the Florida currents. By putting the sensors 1.1 kilometers apart from Key Largo north to Dania Beach, Shay said, and by collecting data every 30 minutes for the past 10 years, Shay said he is noticing trends. He has been able to track the rise in sea level—about 1.1 centimeters per year—as well as water the temperature of the ocean, which will be useful in evaluating the risk of tropical cyclones, he said.

Nick Shay, professor of oceanography in the Ocean Sciences Department at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, has developed the Southeast Coastal Ocean Observing Regional Association, a nonprofit organization that works to track data on the oceans. As a result of the organization’s funding, Shay has put in place a network of 13 ocean radars off the Florida coastline to track data on the ocean and the Florida currents. By putting the sensors 1.1 kilometers apart from Key Largo north to Dania Beach, Shay said, and by collecting data every 30 minutes for the past 10 years, Shay said he is noticing trends. He has been able to track the rise in sea level—about 1.1 centimeters per year—as well as water the temperature of the ocean, which will be useful in evaluating the risk of tropical cyclones, he said.

“We want to learn about the role of the ocean in moderating intensity of storms,” Shay said. In addition, he said they are now able to measure the strength of the Florida current, and can notice correlations between the strength of the current, as well as sea level rise. “We’ve noticed a decrease in the speed of the Florida current during highest king tides in the fall,” he added.

Maria Caballero Espejo, a student from the Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molina in Peru, described her research about the impacts of massive rainfall in Peru during strong El Niño weather events. In the past 30 years, Peru’s economy has faltered each time the strong rainfall event hit the South American country, and widespread mudslides and flooding created dangerous conditions, Espejo said. Therefore, she created a solution—“a soil bioengineering and planting strategy to decrease the susceptibility of mass movement by 10 to 15 percent.”

Dr. Armen Henderson, a University of Miami physician specializing in internal medicine, explained how he is working to combat the effects of climate change on poor and minority populations in South Florida. Henderson founded Dade County Street Response Disaster Relief with medical student Lena Carleton after he noticed the disparity in response to Hurricane Irma. Through this organization, physicians from South Florida visit shelters.

“After Hurricane Irma, I thought that in the U.S. we would have things to keep people safe, but I noticed a very disparate response, and resource allocations were different depending on the area,” Henderson said.

--- Janette Neuwahl Tannen

Wednesday morning: From disaster risk to resilience

Throughout his career, Roger Pulwarty, senior scientist with the NOAA Physical Sciences Division’s Earth Systems Research Laboratory, has helped design and lead programs focused on climate, impacts, and services.

Throughout his career, Roger Pulwarty, senior scientist with the NOAA Physical Sciences Division’s Earth Systems Research Laboratory, has helped design and lead programs focused on climate, impacts, and services.

During a presentation at the Miami Climate Symposium, he shared some alarming data as well as his insights on disaster risk and resilience:

• Adaptation requires science that assesses dynamic risks, analyzes decisions, identifies vulnerabilities, improves foresight, and develops practical options.

• From 2013 to 2016, the Caribbean multiyear drought was the most severe and extensive period of dry conditions in the Caribbean and Central America since at least 1950—with the drought appearing to be related not only to El Nino-driven precipitation deficits, but also to temperature-driven increases in potential evapotranspiration.

• More than $123 million in total payouts were given to 12 CARICOM (the Caribbean Community) member nations impacted by storms since 2007.

• An increase in 2.0 degrees centigrade will result in even additional significant changes in regional climate, taking the region closer to climates it has never experienced to date.

“Every community must decide what level of risk they are willing to endure,” said Pulwarty. “Our fundamental question is not just that it makes for a hard choice, [but] we must show how it makes money by planning up front.”

--- Robert C. Jones Jr.

Wednesday morning: Columbia University researcher talks present and future hurricane activity

Look at the climate models They will ultimately tell us if our climate will continue to warm at what seems like a breakneck pace. Data from NASA, for example, recently showed that 2019 was the second hottest year on record. But what are the models telling us about global warming’s impact on present and future hurricane activity?

Look at the climate models They will ultimately tell us if our climate will continue to warm at what seems like a breakneck pace. Data from NASA, for example, recently showed that 2019 was the second hottest year on record. But what are the models telling us about global warming’s impact on present and future hurricane activity?

Adam Sobel, professor of applied physics and applied mathematics, and of earth and environmental sciences at Columbia University, tackled that question during a half-hour presentation.

With an auditorium filled with researchers and scientists looking on, Sobel opened his talk with data showing that the answer to that question is not always clear. He noted that while an early consensus a few years ago concluded that tropical cyclone activity would decrease, more recent and credible models predict frequency increases.

Sobel—who directs Columbia’s Initiative on Extreme Weather and Climate and will deliver the keynote address at the symposium's public forum on Friday at the Watsco Center on the University of Miami’s Coral Gables campus—detailed some of his own research, which found aerosol cooling reduces tropical cyclone potential intensity more strongly than greenhouse gas (GHG) warming increases it.

It's that tug of war between aerosols and GHGs that intrigued the audience.

Sobel left the audience with something to ponder: While expected tropical cyclone intensity increases have likely been muted by aerosol cooling, which is about two times as effective as greenhouse gas warming in increasing potential intensity, GHGs will increasingly win out in the future when it comes to storm intensification.

--- Robert C. Jones Jr.

Wednesday morning: Students studying climate change monitoring the symposium

The next generation is ready for change. Several students who are studying at the Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, listened intently at the symposium on extreme weather and climate change. Kelsey Malloy, an atmospheric science doctoral student, is proud that her school is leading the conversation.

The next generation is ready for change. Several students who are studying at the Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, listened intently at the symposium on extreme weather and climate change. Kelsey Malloy, an atmospheric science doctoral student, is proud that her school is leading the conversation.

“I think this is a one-of-a-kind symposium that the U has put together. Scientists are addressing extremes and how that relates to Miami at the local level, but also at the national level as well, which I think is really unique. I’m excited to see the range of topics that they have put together,” she said.

Kayla Besong, a doctoral student also studying atmospheric sciences, believes that these types of events are important in spreading the message on the research that is going on in climate science.

“South Florida is extremely vulnerable. It is important to bring together not only scientists but everyone that makes up a community to figure out how to be more sustainable. It increases our resiliency,” said Besong.

Students from across the country traveled to South Florida to learn more from the symposium. Many, including Gavin Madakumbura, who is a University of California, Los Angeles, student studying atmospheric science, finds the symposium an important learning experience.

“The speakers are the top researchers in their field. I came here in a group to learn more about climate change from the eastern perspective,” he said. “It’s interesting to learn more about atmospheric phenomenon, because on the West Coast we suffer from wildfires and droughts, whereas here people are prone to cyclones and flooding.”

--- Amanda M. Perez

Wednesday morning: Key Biscayne’s unique positioning

From keeping the island's shoreline intact to stopping property values from decreasing, dealing with the problems of sea level rise are immense for Key Biscayne, a Miami-Dade municipality that is front and center on the issue of climate change.

From keeping the island's shoreline intact to stopping property values from decreasing, dealing with the problems of sea level rise are immense for Key Biscayne, a Miami-Dade municipality that is front and center on the issue of climate change.

Mayor Mike Davey and Village Manager Andrea Agha discussed the Key Biscayne’s efforts, including millions of dollars in beach restoration projects, as well as a strategy to update aging infrastructure that is now falling victim to rising sea levels.

“We are losing five feet of beach each year,” Agha said. “And right after we finished a sand restoration project, Irma came and washed everything away.”

Their current strategy: Apply to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for help. The federal agency is doing coastal restoration projects across the country; however, Key Biscayne currently is not included in their protection plan. “We need a guarantee of federal assistance and we need it in the long term,” Agha said.

Thanking the scientists for their work, she appealed to the audience for guidance and future assistance so that Key Biscayne, and its approximately 13,000 residents, can remain a viable part of Miami-Dade County. “We need to implement solutions now, but they are bigger than what we can handle as a small municipality,” she said. “Our residents have real fears, they are facing real risks. They see it every day and therefore, we are looking to the community of engineers and scientists to help us make the best decisions we can make.”

--- Janette Neuwahl Tannen and Robert C. Jones Jr.

Wednesday morning: Tropical cyclones expected to increase in strength

Although it is difficult to make a direct link between tropical cyclones and human-created climate change, two top meteorologists said that as the earth continues to warm, the world can expect more rainfall and hurricanes of a greater intensity.

Although it is difficult to make a direct link between tropical cyclones and human-created climate change, two top meteorologists said that as the earth continues to warm, the world can expect more rainfall and hurricanes of a greater intensity.

Research meteorologist Tom Knutson, of the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration’s geophysical fluid dynamics laboratory, shared models and weather observations he has studied from all over the world. Knutson said that although models provide strong evidence for humans’ effect on the global mean temperature, there is no evidence to offer a clear relationship between climate change and storms.

However, Knutson did report that there is evidence that as time goes on there will likely be more rainfall than the models predict. With rising sea levels, this will compound flooding issues, he said.

“The thing we are most confident about is sea level rise will increase the risk of higher storm inundation levels,” Knutson said, adding that “there is a very strong moistening trend and there’s evidence for human influence [with that].”

Knutson and Christina Patricola, a meteorologist at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, also indicated that although forecasters are predicting fewer tropical cyclones in the future, those that do form will likely be more menacing.

“There may be fewer storms; but of those that happen, they will be more intense. That’s the type of change we would expect,” Knutson said. His lab predicts a 34 percent increase in category 4 or category 5 storms globally.

--- Janette Neuwahl Tannen

Wednesday morning: Provost Jeffrey Duerk delivers opening remarks

With drought affecting parts of Africa, Australia suffering some of the worse bushfires in its history, and the Bahamas still reeling from the effects of a powerful cyclone that was one of the most intense storms in Atlantic Hurricane season history, a landmark summit examining the impact of climate change on extreme weather got underway at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science early Wednesday. The conference helps meet the institution’s goals of investigating “not only how to beat climate change but how to mitigate it,” said Jeffrey Duerk, provost and executive vice president for academic affairs.

Pointing out that the University has long recognized the “compelling challenge of climate change,” Duerk noted the University of Miami Laboratory for Integrative Knowledge (U-LINK), which supports innovative interdisciplinary research, is addressing climate change with two specific projects—one that will transplant some 150,000 corals in an effort to combat rising sea levels and another that will improve the process to communicate the effects of hurricanes as they approach U.S. coastlines.

The symposium began with Miami temperatures in the low 40’s, similar to weather conditions 10 years ago, when the Rosenstiel School hosted another climate conference on its Virginia Key campus.

Back then, “we couldn’t figure out how to turn the air conditioner off,” said Ben Kirtman, a professor of atmospheric sciences who, along with climatologist Amy Clement, organized this year's conference. “So at least we’re a little bit warmerin here today.”

Kirtman said he hopes the symposium will serve "as an open dialogue on how the best available science is being used to guide decisions.”

He sentiments were echoed by Roni Avissar, dean of the Rosenstiel School and a climatologist who studies the way Amazon deforestation affects precipitation patterns around the world, who described Miami as “a city at the epicenter of climate change.” No matter what happens, Miami will always be one of he most sensitive cities to suffer the consequences of changing climate, especially sea level rise, Avissar said. He noted that a significant portion of faculty and students at the University are studying climate, adding that the topic is “a central activity" of the Rosenstiel School.

--- Robert C. Jones Jr.

Wednesday morning: Sea captain has seen all types of extreme weather

Today it is docked, but ordinarily the Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science catamaran R/V F. G. Walton Smith plies ocean waters anywhere from the Gulf of Mexico to the Caribbean, transporting scientists and technicians as they conduct research that can range from the flow of crude oil in the sea to the migration habits of pelagic fish.

Today it is docked, but ordinarily the Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science catamaran R/V F. G. Walton Smith plies ocean waters anywhere from the Gulf of Mexico to the Caribbean, transporting scientists and technicians as they conduct research that can range from the flow of crude oil in the sea to the migration habits of pelagic fish.

And during some of those voyages, the vessel undoubtedly encounters extreme weather that a growing chorus of scientists believes is only worsening due to the effects of climate change.

Shawn Lake, captain of the F.G. Walton Smith, has seen his fair share of extreme weather while piloting the vessel. “But we usually run away from it,” he said early Wednesday just before the start of the University of Miami’s three-day summit, the Miami Climate Symposium 2020, which is examining how global climatic conditions are impacting weather events such as tropical cyclones, drought, and extreme flooding. “We have two satellite systems onboard that give us constant weather information,” Lake said. Those systems, along with others, came in handy three years ago when the vessel spent several weeks in Caribbean waters near the U.S. Virgin Islands, as scientists investigated Hurricane Irma’s impact on coral reefs in the region.

Lake, who was overseeing routine maintenance on the ship early Wednesday, believes the conference is vital. “People have to get together to talk about problems, and this [climate change’s impact on weather] is a big one.”

--- Robert C. Jones Jr.

Miami Climate Symposium 2020 sponsors: Florida Power & Light Company, University of Miami NOAA Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies, National Science Foundation, William J. Gallwey, III Esquire, Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, Royal Caribbean Cruise Lines, Key Biscayne Community Foundation, The Village of Key Biscayne, University of Miami Abess Center for Ecosystem Science and Policy, Atlantic Council Adrienne Arsht-Rockefeller Foundation Resilience Center, Miami Dade County, Southeast Coastal Ocean Observing Regional Association, The Florida Climate Institute and Diane Davis-Merrill Lynch Wealth Management, along with media partners NBC6 Miami and CNN.