Carried by the trade winds, the massive dust plume has almost completed its nearly 5,000-mile journey. It blanketed parts of the Caribbean only days ago. Now, it’s simply a waiting game, as residents across the southeastern United States anticipate its arrival.

Blown directly from the Saharan Desert across the tropical Atlantic Ocean, dust outbreaks such as the one making its way to the United States are fairly common during this time of year, easily reaching the Lesser Antilles and, several times a year, extending to South Florida and the Gulf of Mexico.

“It’s common in that, yes, every year there’s dust that comes into the area. You can see it all over the Caribbean, and you see it in the air-quality measurements that are made in the southern states fairly routinely,” said Joseph Prospero, a professor emeritus of atmospheric sciences at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science.

“What’s unusual about this event is that it is huge,” Prospero said. “There’s been high concentrations of dust pouring off the west coast of North Africa for the past two weeks. And the concentrations in this outbreak are something I can’t ever recall seeing in all the decades I’ve been studying such phenomena.”

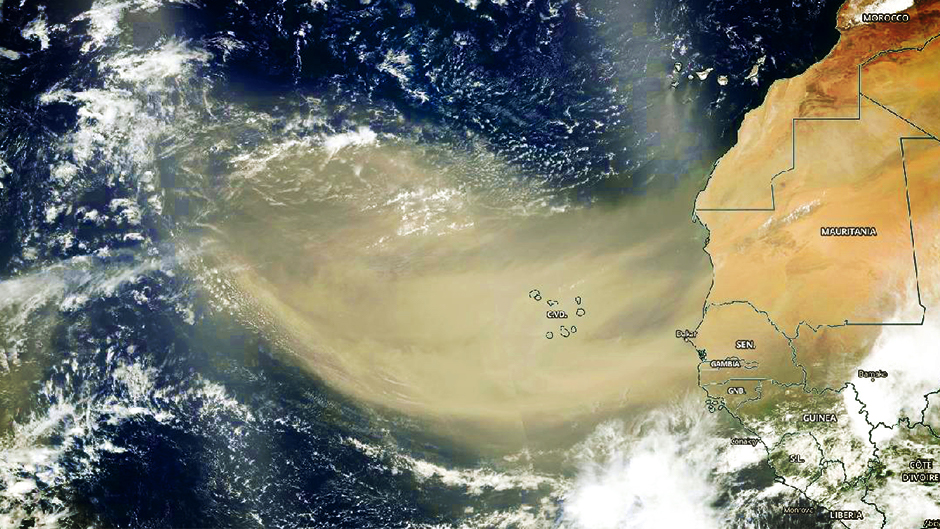

Satellites have provided images of the dust in striking detail, showing the large, light brown dust plume extending from Africa’s west coast. Even NASA astronaut Doug Hurley has contributed to the spectacular gallery of images of the plume, taking and sharing via Twitter an image of the giant plume while aboard the International Space Station.

Satellites have provided images of the dust in striking detail, showing the large, light brown dust plume extending from Africa’s west coast. Even NASA astronaut Doug Hurley has contributed to the spectacular gallery of images of the plume, taking and sharing via Twitter an image of the giant plume while aboard the International Space Station.

When it makes its grand U.S. entrance, residents in some parts of the country can expect to see vibrant sunsets and sunrises as a result of the dust. “When you get dust in the area, the whole sky changes, even when you have relatively modest amounts,” Prospero said. “You’re not getting so much direct light from the sun. The dust acts like a huge diffuser and gives a soft, warm glow to the landscape. If you’re out in the country, you could see it more clearly. In an urban setting, where there’s more pollution, the effect is missed.”

But the dust could also have detrimental effects on health, putting those with underlying medical conditions at risk, said Naresh Kumar, an associate professor of environmental health in the Department of Public Health Sciences at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine.

“People with asthma, COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), and other respiratory ailments face the increased risk of flare-ups,” Kumar said. “And since the dust also carries foreign bacteria, inhalable particles could raise the risks of allergic reactions and infections.”

In the days ahead, Kumar will be monitoring the air sensors he has installed on rooftops on the Rosenstiel and Medical campuses, capturing real-time data that will be used for future experiments on the health impacts of dust and particulate matter. He will also be deploying special instruments to capture transported dust for follow-up studies. “We have to learn more about how toxic this dust could be compared to our own local dust,” he said. “It’s dust we’re not used to, and our bodies could react differently to it.”

Kumar and others recently completed a study on the health impacts of Saharan dust, showing that the risk of COPD increases significantly with exposure to the particles. Paquita Zuidema, a professor of atmospheric sciences, participated in the study, providing air-quality data used in the research. Their study is yet to be published.

Other University of Miami researchers are also involved in studies that examine Saharan dust and its impacts.

Cassie Gaston, assistant professor of atmospheric sciences, and her team are currently collaborating with researchers at the University of Puerto Rico’s Río Piedras Campus, providing them with air filters that are used to quantify how much of the Saharan dust is contributing to elevated levels of particles in the air during the summertime. Her team is also deploying air-sampling devices in Barbados at the Rosenstiel School’s Barbados Atmospheric Chemistry Observatory.

“There’s been speculation that when you get these large dust plumes coming over, they could cause issues for people in the Caribbean who suffer from asthma, although that impact hasn’t been clearly established yet,” Gaston said.

Prospero also has an upcoming paper looking at the transport of African dust throughout South America and its impact on terrestrial ecosystems there. The dust’s contribution to red tide is an area that needs further exploring, he noted.

“There’s been a long discussion on African dust and its impact on harmful algal blooms,” he explained. “The dust contains a lot of iron that serves to fertilize certain marine organisms, which could lead to enhanced production of algal blooms.”

The dust plumes, said Gaston, do have some beneficial aspects. In a study published last year, her research group, which examines biogeochemical cycles and the way dust impacts the ocean, revealed that the plumes, as well as smoke from burning fires in Africa, are “sources of nutrients that feed the Amazon rainforest.”

The dust can also impact storm activity, creating just the right atmospheric conditions that weaken tropical cyclones. “When this dry, dusty air exists in the low-to-mid layers of the atmosphere, it chokes out cloud formation,” explained Brian McNoldy, a senior research associate and hurricane expert at the Rosenstiel School. “If a tropical cyclone is near the Saharan air layer, it can ingest that dry air and weaken or dissipate. It’s a perfectly normal feature of the atmosphere this time of year.”

Just why this dust event is so large is a mystery right now. “That’s what a lot of us are now looking into—the meteorological characteristics that led to this huge storm. We’re measuring aerosol optical depth that we’ve never seen before—it’s that dense,” said Prospero, adding that the large plume could reach the Canadian border.

Precipitation and changing wind patterns could play a role in the size and transport of the dust. “But at this point, we don’t know whether there’s a rainfall issue in Africa,” he said. “We do know that when you have drought and drier conditions in Africa, you have more dust.”

For those with respiratory ailments, Kumar recommended a three-pronged approach to deal with the upcoming dust event. “Don’t go outdoors, or reduce the amount of time you spend outdoors,” he said. “If you have no other choice, use a mask or some other form of filtration device to reduce exposure. And if you’re on any medication, make sure that you take it.”