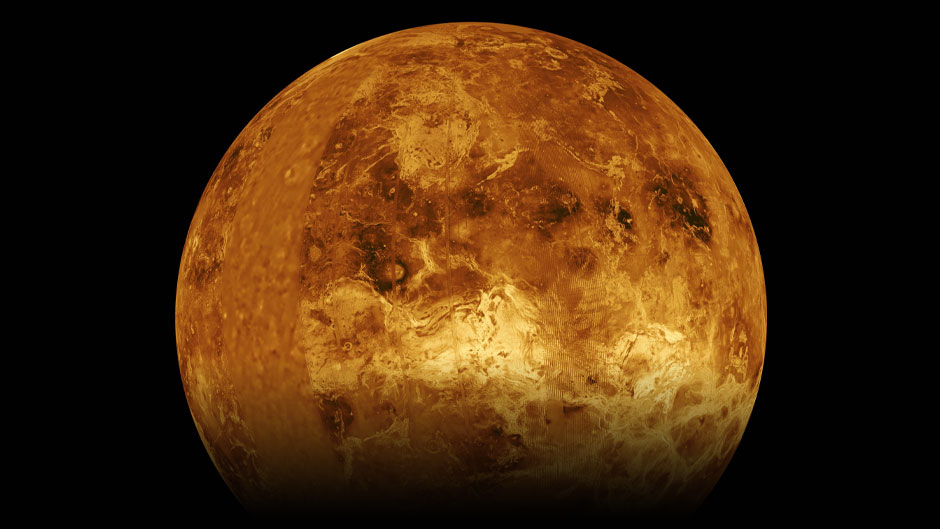

For decades, scientists have always looked to Mars for signs of extraterrestrial life, sending probes to explore the Red Planet’s surface, and, for the most part, dismissing Venus—a planet perpetually shrouded in clouds of sulfuric acid—as a habitat for anything living.

But recently, an international team of researchers, using powerful radio telescopes, detected phosphine—a toxic gas produced by microbial life—in the cloud decks of Venus. The scientists, who reported their findings in the journal Nature Astronomy, are not claiming to have definitively discovered life in the Venusian atmosphere, only that their discovery is confirmation for “anomalous and unexplained chemistry.” Further investigation into the source of the phosphine, and whether it is a signature for life in the clouds of Venus, is needed, they said.

Their discovery nonetheless has fueled renewed interest in Venus as a planet hospitable to life, with some scientists calling for probes to be sent to Earth’s nearest neighbor. Only a handful of unmanned exploratory aircraft have ever sniffed Venus’ atmosphere.

“Now is absolutely the right time for sending another probe,” said Lynn Holly Sargent, a Ph.D. candidate in the University of Miami College of Engineering, who has conducted research on using magnetic fields to create radiation shields on the surface of Mars. “There are still many questions regarding how the phosphine, which is a potential indicator of microbial life, made its way into the planet’s atmosphere and when. In fact, we don’t know nearly as much about Venus as we do about Mars.”

Venus has been called Earth’s evil twin. It is similar in size and structure and may have once looked and behaved like Earth. But today, conditions on the planet are extreme. The hottest planet in the solar system, Venus has a thick, toxic atmosphere filled with carbon dioxide, and the crushing air pressure at its surface is more than 90 times that of Earth.

That life could exist in such a harsh environment would seem unlikely. “The authors of the study are aware of that. In fact, they state it, saying that ‘there are substantial conceptual problems for the idea of life in Venus’ clouds,’ ” said Carl D. Hoff, professor of chemistry in the College of Arts and Sciences. “They are proposing life may exist in the clouds. Others, including Carl Sagan, have made similar conjectures in the past. It is hard to imagine how that would work. On the other hand, no one would have predicted the kind of life in the deep hydrothermal vents of our Pacific Ocean.”

Still, the possibility of extraterrestrial life in Venus’ atmosphere, no matter how remote, has some scientists intrigued. “The possibility of life forms elsewhere in our solar system, even at the microorganism level, is amazing and would certainly warrant further investigation to confirm it and understand the nature of such life,” said Massimiliano Galeazzi, professor and associate chair of physics in the University of Miami College of Arts and Sciences, who studies X-rays in the solar system, specifically in the gas between planets.

NASA, which has sent probes to Venus before, could, in fact, be sending another one to the planet in the near future. Two spacecraft—DAVINCI+, which would analyze Venus’ atmosphere to understand how it formed and evolved, and VERITAS, which would map Venus’ surface to learn more about the planet’s geologic history—are competing against missions to Neptune’s moon Triton and Jupiter’s moon Io to become the space agency’s next Discovery Program mission. Final selections will be made next year.

University of Miami faculty members give their insight on the phosphine fingerprint, the amazing technology used in the discovery, and the future exploration of Venus.

The astronomers who detected phosphine in the Venusian atmosphere used powerful radio telescopes. How are such telescopes able to make those measurements?

The radio telescopes that detected phosphine used spectroscopy to make the detection. All elements, as well as molecules in phosphine’s case, have unique spectroscopic signatures akin to unique fingerprints for humans. Even though the objects are millions of miles away, or even all the way across the cosmos, we can determine their chemical makeup by measuring either the light they emit (emission spectroscopy) or the light they absorb (absorption spectroscopy). Call it Crime Scene Investigator on steroids, if you will.

—Joshua Gundersen, professor of physics in the College of Arts and Sciences

Is it possible that the phosphine gas detected in the Venus atmosphere could be the result of other processes unrelated to life?

Reactions and conditions that could produce PH3 [phosphine] can be imagined, but it is not certain, and the authors are aware that they have not yet proven that the source of their spectral observations are conclusive. In their abstract, they state that other PH3 spectral features should be sought. It is not a slam dunk that the PH3 is there in excess in the first place. This is written by a team of 19 experts, and it is credible but not definite.

—Carl D. Hoff, professor of chemistry in the College of Arts and Sciences

The scientists said their discovery needs additional investigation. If it turns out that the phosphine detected in the clouds of Venus is not a signature of life, would the chemical process that produced the gas be worth investigating?

Not in my view. PH3 [phosphine] is a highly toxic gas used in the electronics industry. A lot is known about its chemical reactions on Earth. Even if there is bacterial life in the clouds of Venus, it is not clear that this should be a top priority for major funding at this time.

—Carl D. Hoff, professor of chemistry in the College of Arts and Sciences

Because of the extreme conditions on Venus, wouldn’t any future missions to the planet be short-lived like those of the past?

Maybe. The DAVINCI+ mission proposes sending individual payloads down to the surface of Venus from a central hub, each payload gathering information about the atmosphere along the way down and relaying that information back to Earth. In this way, the hub does not need to be designed to withstand the undesirable atmospheric conditions on the closest part of the surface, and with multiple probes being sent down to the surface, there is a higher chance of gathering data. In terms of the VERITAS mission, it is noted that there have been other successful orbiters to survey Venus, just not with the intention of fully mapping the surface, and not with today’s technology.

—Lynn Holly Sargent, Ph.D. candidate in mechanical and aerospace engineering in the College of Engineering