When surgeons go into the operating room, they typically have studied a patient’s troubled organs, but they always have to keep MRI or CT scans along the wall and take X-rays throughout the procedure to ensure they are following the unique anatomy of each patient.

But what if a 3D hologram of the patient’s organ could float next to the physicians during surgery, helping them to make more precise incisions?

This is the hope of a yearlong collaboration between two University of Miami neurosurgeons, Dr. Timur Urakov and Dr. Michael Ivan, along with the University’s Innovate lab, which uses augmented reality technology in headsets from Plantation-based company, Magic Leap. Augmented reality is a type of spatial computing that allows users to see and interact with virtual objects, like a hologram of a patient’s brain tumor, existing within the physical world.

“Visualization and knowledge of anatomy in surgery is one of the most important things, and having 3D anatomy of the brain and spine to help us explain procedures to patients, to teach our students, and to operate is critical,” said Ivan, an assistant professor of neurosurgery at the Miller School of Medicine and director of research at the Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center Brain Tumor Initiative. “Also, being able to bring in 3D-overlaid images of the brain and spine as you operate adds a level of understanding and accuracy for doctors, residents, surgical assistants, and fellows.”

Their idea is quickly coming to fruition. Buoyed by a Magic Leap grant awarded to the doctors in January, Ivan and Urakov began working with Max Cacchione, director of innovation for University of Miami Information Technology. Cacchione quickly assembled a team of student programmers, including Lenny Martinez, Manish Garg, Andrew Ignacio Gonzalez, and Brandon Torres.

With samples of MRI images—which are taken in 3D but, until recently, have been analyzed only in 2D—Cacchione and his team worked on creating software to convert the images into 3D holograms through augmented reality. With this new software, doctors and patients can view the holograms on top of the physical world using Magic Leap 1 headsets. This summer, Ivan and Urakov began testing the program and were able to show some patients a 3D version of their brain or spine during presurgery consultations. That is the same image the surgeons can use on top of the patient’s organs during surgery to help illuminate the troubled areas.

“No longer do I have to look on the other side of the room; with these glasses and this software, we can see where the windows and veins are in the brain,” Ivan said.

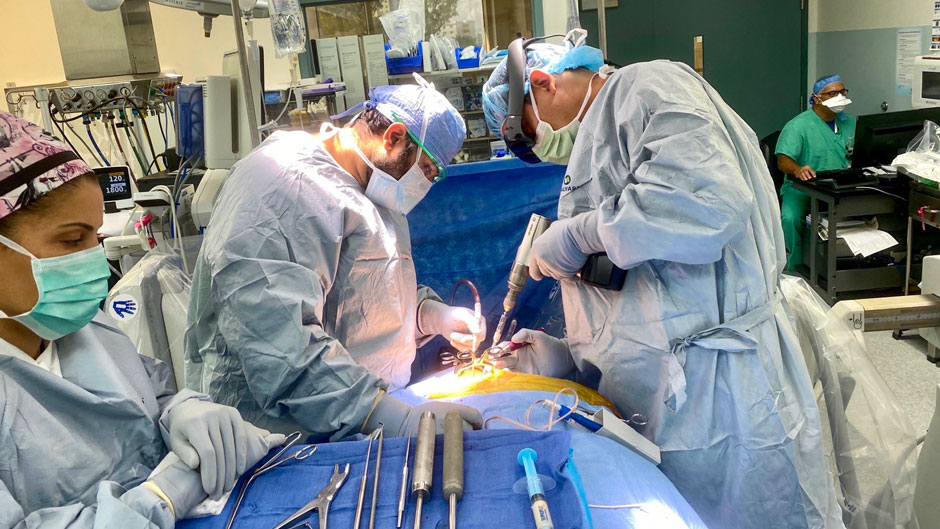

Recently, Urakov donned his Magic Leap headset during a surgery to implant screws into a patient’s spine. The hologram of the patient’s spine hovered just above his body, helping him to determine the corrent angles in which to place the screws.

“Spatial computing and augmented reality allow you to have a digital projection of where you want to go, and this gives you a 360-degree view immediately to see the depth and orientation of the bones,” said Urakov, assistant professor of clinical neurosurgery at the Miller School. “It’s a much more intuitive, more ergonomic, and much more efficient way to do surgery.”

Yet, there are even more benefits to the software, which they named a DICOM visualizer, Ivan said.

The program allows surgeons to demonstrate to patients exactly what they will be doing in the operating room.

“Some people are very interested and excited about how a surgery will go, so this can put them at ease,” Ivan said.

The program allows doctors to label or highlight parts of the hologram in different colors, which can help them explain their reasoning to patients or students for certain surgical decisions. Surgeons can use the software to categorize tissue as healthy, questionable, or tumor-laden, Ivan added.

The technology also prevents surgeons and other health care professionals from being exposed to radiation from the multiple scans that are often requiredduring surgery.

Another benefit is that the DICOM visualizer may pave the way for more minimally invasive surgeries, Ivan said, because it provides surgeons with what he calls “X-ray vision” to view the anatomy underneath the skin, enabling them to make even smaller incisions.

As the surgeons and the Innovate team continue to test and refine the software, they hope to make the holograms even more interactive, Urakov said. With the addition of 5G Edge computing, available on the Coral Gables Campus, Cacchione believes this program will be able to load images and create holograms even faster, as well as connect surgeons with medical experts outside of the operating room.

In the meantime, Ivan and Urakov hope other physicians in the Miller School will use the technology to improve their operating efficiency. Ivan recently presented to physicians in the Department of Otolaryngology and found a receptive audience among the ear, nose, and throat surgeons.

“It really has the possibility for helping very many areas of medicine,” Ivan said. “And we are hoping to create a program that can be commercialized and used for many different specialties.”

To learn more about the DICOM visualizer, you can view tutorials on the program created by UMIT. Here is Part 1, and Part 2.