It’s finally over, but the 2020 Atlantic hurricane season will forever be imprinted in our memory—and for good reason.

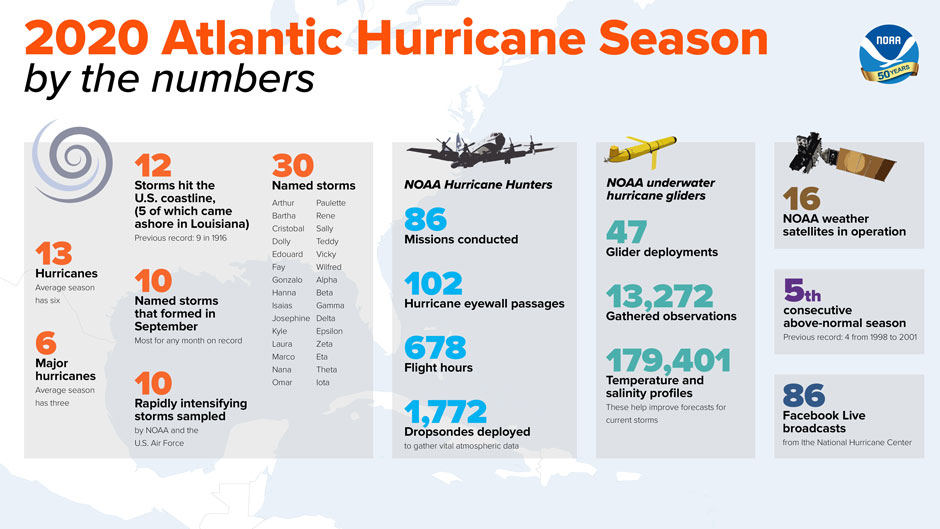

There were 30 named storms; 12 of them hit U.S. shores. Both were record-breaking numbers.

And it started early, with tropical storm Arthur forming off the east coast of Florida in mid-May, making it the sixth straight year that a tropical cyclone formed before the official June 1 start date of hurricane season.

From there, the season snowballed and never really let up. Six storms— Laura, Teddy, Delta, Epsilon, Eta, and Iota—reached major hurricane status (Category 3 or larger), tying the record for the second highest number of major storms in a season.

Louisiana, forever synonymous with the destruction wrought by Hurricane Katrina in 2005, took a thrashing, with five storms hitting the southeastern state.

Hurricane Iota made landfall in Nicaragua as a dangerous Category 4 storm on Nov. 16, pummeling the country’s northeastern coast with 155-mile-per-hour winds and becoming the strongest storm ever recorded in the Atlantic that late in the season.

And for the second time in recorded history, the National Hurricane Center exhausted every name on the preset list of tropical cyclone names for the Atlantic basin, necessitating the use of the Greek alphabet to name storms for the remainder of the season.

It wasn’t as if forecasters were caught off guard. Back in May, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) accurately predicted an above-normal season with a strong possibility of it being extremely active. As for the factors that conspired to make the season an extremely busy one, “the jury is still out,” said Brian McNoldy, senior research associate and tropical cyclone expert at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science.

“But ocean temperatures were a bit warmer than average, and a weak La Niña [the colder counterpart of El Niño] probably decreased the vertical wind shear across the tropical Atlantic somewhat,” McNoldy said, referring to two climate conditions that play a role in storm activity. “There was a notable absence of long-track storms in the deep tropics from Africa to the central Caribbean, but then a notable clustering of storms in the western Caribbean and up into the Gulf of Mexico. Also, while there were a record-breaking 30 named storms, 17 of them either lasted for three days or less and/or peaked as a mid-range tropical storm.”

The clustering of storms in the western Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico was one of the attributes that set the 2020 season apart. “Once a storm is in those areas, it almost has to make landfall somewhere because of the geography,” he said. “And bad luck was in full force.”

Nicaragua, he noted, experienced two Category 4 landfalls at the same location two weeks apart—first Eta and then Iota—and five named storms, including three hurricanes, struck Louisiana. This was a devastating year for residents in Central America and in the southern United States.

The climate change factor

The record-breaking season has rekindled intense discussion over the link between global warming and Atlantic hurricanes. But while scientists cannot say for certain that human-induced climate change will lead to prolonged and more potent seasons, the question as to whether our changing climate is making storms worse is “essentially settled science,” said Amy Clement, a professor of atmospheric sciences at the Rosenstiel School, who is an expert in climate modeling.

“This includes the simple fact that a warmer atmosphere holds more water vapor, so storm-related rainfall increases as climate warms,” Clement said. “And sea level is higher. So again, quite simply, higher sea levels mean worse storm surge impacts.”

Clement noted that a recent Rosenstiel School study shows just how closely linked swings in Atlantic temperatures— one of the main drivers of changes in hurricane activity—are to human activities. “This includes, of course, an upward trend in the temperatures, which, unfortunately, is what we should expect for the future. But it also includes times in the past when soot from coal-burning caused temperatures to trend somewhat downward,” she said. “Humans are profoundly impacting the climate and along with that the conditions for hurricane development.”

Indeed, an increase in the likelihood and severity of hurricane-induced flooding is the primary impact of a warming climate on hurricanes, agreed Brian Soden, a professor of atmospheric sciences, who uses satellite observations to test and improve computer simulations of Earth’s climate. “This is a result of increased rainfall, due to a more humid environment, and higher sea levels, which both increase storm surge and reduce the ability of storm water to runoff from the land into the ocean,” he explained.

With 12 of the record-shattering season’s 30 storms hitting U.S. shores, questions about managed retreat—the practice of moving people and infrastructure out of harm’s way as a defense against natural disasters like destructive storms—are also likely to be debated more intensely.

“It is definitely the case that questions of retreat, through buyouts and also other means, are increasingly on the radar,” said Katharine Mach, an associate professor of marine ecosystems and society, referring to a program in which the Federal Emergency Management Agency purchases properties in flood-prone areas, turning the land into open space.

“Science-society dialogues about climate-related displacement, migration, and retreat have been ramping up tremendously on this topic. And this year’s intense hurricane season has only served to amplify the considerations,” Mach said. “Questions of insurance, bond ratings, and other dimensions of finance are also pressing, and there are important uncertainties about when and how changes in markets and policies will unfold.”

Looking ahead

The absence of El Niño, during which surface waters in the central and eastern Pacific Ocean become significantly warmer than usual, is one factor that contributed to this year’s record-shattering season, according to forecasters. With the 2020 season still in our rearview mirror, what does next year hold for storm-weary coastal residents?

“El Niño/La Niña can sometimes be forecast more than one year in advance, but this time the models are not showing much confidence,” said Emily Becker, associate director of the University of Miami-NOAA Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies. “Official forecasts extend through late summer, early fall, and overall the most favored outcome is neutral, but I would not really lean on that.”

If there’s any silver lining to the 2020 season, it’s that the increased storm activity kept scientists busy, giving them more opportunities to conduct research that could lead to a better understanding of hurricanes. David Nolan, a professor of atmospheric sciences at the Rosenstiel School, participated in intercept missions for three different storms: Laura, Sally, and Delta.

“In the third storm, Hurricane Delta, my graduate student, Rebecca Evans, joined me, and we were able to deploy muon detectors lent to us by some friends at MIT,” Nolan said. “These detect muons [elementary particles similar to the electron] caused by cosmic rays. The number of muons increases as atmospheric pressure decreases, so we wanted to see if this change could be seen near the center of a hurricane.”

The season may have officially concluded on Nov. 30, but storms can and have developed beyond the ending date.

McNoldy, a tropical weather expert for The Washington Post’s Capital Weather Gang, weighed in on other aspects of the historic 2020 hurricane season.

Was human-induced climate change a factor in the busy season?

This is always a difficult question to answer. Yes, climate change was a factor, as it always is. But no particular storm or season can be attributed to climate change. We are very likely going to have fewer than 30 storms in the coming years, but that does not discredit climate change. We might not have any Category 5 hurricanes in the next few seasons, and we most likely won’t have 12 landfalling storms in the U.S. in a single season for a while. What’s important to consider when it comes to climate change is multi-decadal trends. As we zoom in more and more, natural variability becomes increasingly dominant. But the 2020 season will now be a part of the long-term climatology and trends.

How does the 2020 season measure up to others when factoring in the accumulated cyclonic energy (ACE) metric?

ACE is a quantity that basically accounts for the intensity and duration of all storms combined. A short-lived strong storm could generate as much ACE as two long-lived weaker storms. Going back to 1851, this season ended up in 10th place in the ACE rankings. It was well below 2017, 2005, 2004, 1995, and others, mostly because of the large number of weak and/or short-lived storms. Ironically, it was the season’s last and strongest storm, Iota, that pushed it up into 10th place.

As a researcher, what was this season like for you? With so much storm activity, you probably conducted more analyses and research and blogged more than at any other time during your career studying hurricanes.

For as long as I can remember, I have watched tropical cyclones with great interest. There is always something to be learned from the real world: why storms develop or don’t develop, how far in advance models start to show skill, the explosive intensification of certain storms. Whether they work with observations, theory, and/or modeling, I think I speak for most tropical cyclone researchers when I say that nature is the primary inspiration for doing what we do. The goals are to better understand what makes them tick and to better predict their behavior further into the future. Since this season was essentially two seasons compressed into one, it provided us with plenty of interesting cases to analyze in the coming years. But it also got to be exhausting at several points, and I’m not even the one making the forecasts or flying through the storms.