Growing up in Greece, Landolf Rhode-Barbarigos was surrounded by art.

The son of a painter who was also trained as an engineer, the University of Miami assistant professor of engineering learned from his mother that art is not typically utilized. It’s simply appreciated for its beauty.

But when Rhode-Barbarigos saw a piece of art that contained mathematical properties, he was intrigued. He first glimpsed what’s known as a tensegrity structure while in college at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne. The unique system of cables and bars piqued his curiosity, so Rhode-Barbarigos went on to study the form as a graduate student in engineering. Today, he is among just a handful of artists, engineers, scientists, and mathematicians considered tensegrity experts in the world.

“Tensegrity is a structure composed of pre-tensioned cables and bars, and it is the interplay of the forces inside these cables and bars that gives the structure its form and defines its behavior,” said Rhode-Barbarigos, who holds secondary appointments in the School of Architecture and at the Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science. “It’s often a challenge to find an engineer who understands the aesthetic language of tensegrity.”

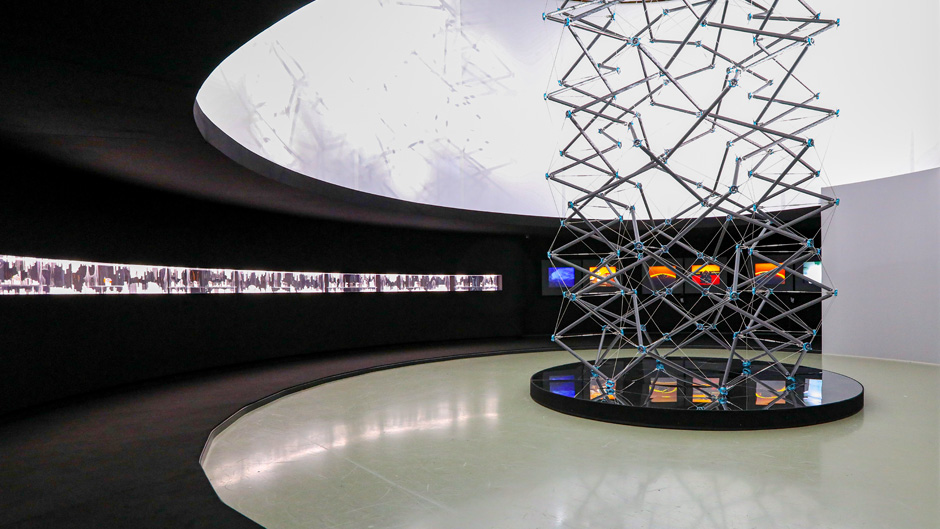

Yet, in early April, a 24-foot high and 10-foot wide tensegrity structure titled “Tencylinder,” designed by artist Clément Vieille, with Rhode-Barbarigos as engineer, and Filippo Broggini and Felix Stampfli as architects, was unveiled in Geneva, Switzerland, to showcase a new line of Hermès watches. Crafted after a year of video conferences to finalize the design and construction, Rhode-Barbarigos said the structure was originally created for Switzerland’s annual 2020 Watches and Wonders trade show. But because of the pandemic, the luxury manufacturer postponed its debut for a year. Two weeks ago, as watch aficionados viewed the new Hermès line at an exclusive in-person event, “Tencylinder” was suspended in the center of the showroom.

“It’s really exciting to see this come together,” said Rhode-Barbarigos. “It’s unique to have projects where you combine an engineering challenge with aesthetics. It’s different because I can apply my research to something unconventional. It’s not an everyday opportunity, and when you build one of these, even a small one, you appreciate how hard it is. Nothing is stable until you reach a certain stage. So, what we accomplished is a big deal and it looks great.”

He now plans to work with Vieille and Broggini to take “Tencylinder” on tour, so that art museums and university students around the world can appreciate the structure and learn about tensegrity. That’s possible because “Tencylinder” is collapsible and easily transportable, a design feat that Rhode-Barbarigos said required extra planning and analysis.

“From an engineering perspective, this opens the door for more structures that could use the tensegrity principles,” he pointed out.

This was not Rhode-Barbarigos’ first tensegrity structure or artistic project. He spent much of his graduate studies in engineering deciphering how tensegrity structures function. His dissertation project was a movable footbridge prototype that uses tensegrity concepts to open and close as needed (presumably, when tall boats need to pass under it). He also worked on a suspended structure of more than 12,000 Bic pens that was displayed in a Paris train station in 2017.

As a faculty member at the University, Rhode-Barbarigos discovered the research of Spanish mathematician Miguel de Guzmán Ozámiz, who proved that all tensegrity structures are based on the same basic units. And once you form the first cell, the rest of the structure can be combinations of that first one. Rhode-Barbarigos then worked with a de Guzmán collaborator, David Orden, from the University of Alcalá in Spain and one of his UM graduate students to build upon the theory and make it applicable to engineers, who focus on the structural behavior of tensegrity structures.

“De Guzmán passed away [in 2004] and nobody really went after his theory, but for me it was the holy grail. And no one had used this before,” he said, adding that this research helped him analyze the stability of “Tencylinder.”

Tensegrity structures were first created by American sculptor Kenneth Snelson in the late 1940s. Although Snelson had experience with photography and painting, he spent his childhood building models of boats and airplanes. As an art student in college, Snelson heard a guest lecture on geometry from architect Buckminster Fuller, who spoke about balancing tension and compression in structures, and the young painter was inspired. Soon after, Snelson—who had always been interested in the interplay of science, engineering, and art—began exploring the role of these forces to create sculptures from suspended cables and bars. When Snelson showed his first sculpture to Fuller, the architect coined the term ‘‘tensegrity’’ to describe the structure. Fuller later developed the geodesic dome using his theories about compression and tension that were confirmed by Snelson’s early pieces. These also drew the attention of experts in the math, science, and engineering fields.

Snelson went on to create tensegrity structures that are featured in museums and as outdoor sculptures in Denver, New York City, Washington, D.C., and even Japan and the Netherlands. He passed away in 2016; but according to Rhode-Barbarigos, NASA scientists continue to use his ideas to build modules for planetary exploration that need to be folded during transport.

“[A tensegrity sculpture] may seem like a series of floating bars that look chaotic, but they are there because the forces are in equilibrium,” said Rhode-Barbarigos. “So, it’s not chaotic or random, it’s actually well-defined.”