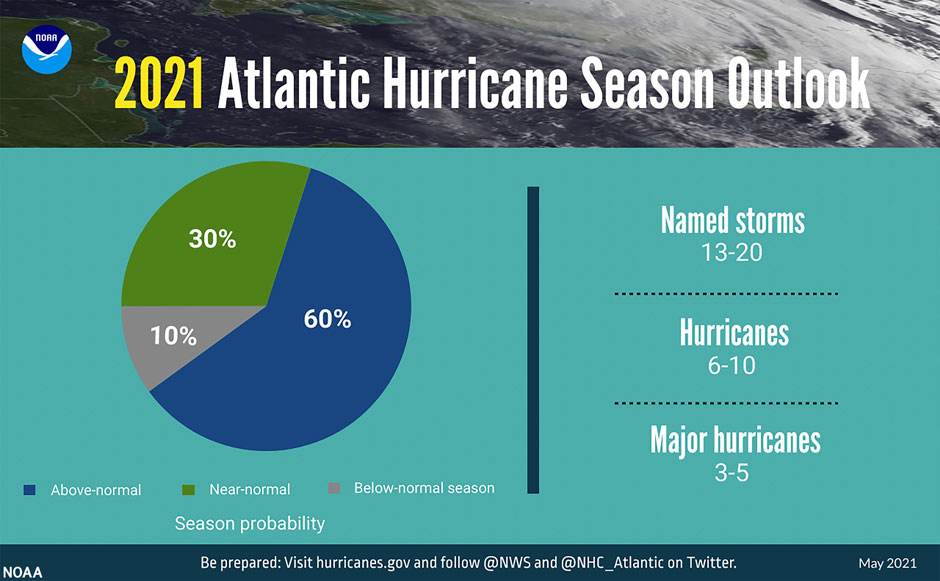

It won’t be quite as historic as last year, but there’s still a 60 percent chance that the 2021 Atlantic hurricane season will be above normal, generating as many as 20 named storms, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) predicts.

NOAA forecasters are calling for 13 to 20 named storms, of which six to 10 could become hurricanes, including three to five major hurricanes.

The season officially starts June 1, but for the seventh year in a row, it has gotten underway early, with subtropical storm Ana forming northeast of Bermuda on May 22. The storm has since dissipated.

The lack of El Niño conditions to counteract the warmer-than-average subtropical Atlantic Ocean has factored into NOAA’s forecast.

“That, plus the lower frequency trends in the Atlantic in terms of temperatures and also current temperatures in the main development region in the Atlantic are all pointing to a stronger-than-normal hurricane season,” said Ben Kirtman, a professor of atmospheric sciences at the Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science. “But the indicators are not necessarily pointing to a hurricane season quite as strong as last year.”

Still, an above-average hurricane season is the last thing storm- and COVID-19-weary emergency managers and residents in coastal states want to hear.

“The emergency management field as well as our University community are feeling COVID fatigue as well as disaster fatigue, which can be a challenge because of the impact it has on a community’s ability to accept the potential of another disaster and its willingness to prepare for it,” said Matthew Shpiner, director of emergency management for the University of Miami.

But while coastal communities may face challenges, Shpiner said the experience of dealing with a pandemic during the past year can help them respond better to the 2021 season.

“We all can think back to March of last year and going to supermarkets and not being able to find toilet paper on the shelves,” he said. “During a hurricane, we think about having inventory of critical items like water, shelf stable food, batteries, and flashlights, and how difficult it can be to get these items at the last minute. It’s a different example of the same concept of the potential mad dash for critical supplies. So, our recent experience can actually put us in a better position to respond to a hurricane, if we can get past the fatigue of dealing with COVID.”

Another area of concern during this storm: Supply chains facing the unequivocal challenge of parrying the impact of oncoming storms while maintaining ongoing efforts to alleviate disruptions caused by the ongoing pandemic, said Murat Erkoc, associate professor of industrial engineering and director of the Center for Advanced Supply Chain Management at the College of Engineering.

“A large storm and its landfall pose consequential risks for supply chains and can significantly delay the process of reaching a new normal,” Erkoc said. “On the other hand, the current environment under COVID-19 with social distancing, ongoing vaccinations, and global shortage of shipping containers can seriously compound the recovery efforts after a tropical storm, especially one that may make landfall in early season. In general, with disasters and disruptions, one plus one is typically more than two as one adds a myriad of barriers for people and organizations seeking recovery in the aftermath of the other.”

NOAA’s forecast comes as President Joe Biden has announced a $1 billion investment in the Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities program, a Federal Emergency Management Agency initiative to help states, tribal governments, and territories prepare for extreme weather events and other disasters.

Biden also announced that NASA will develop a new set of Earth-focused missions to allow scientists and policymakers to better understand and track the effects of climate change. Satellites deployed as part of the Earth System Observatory will work in tandem to create 3D, holistic views of the planet, from bedrock to atmosphere.

“With this administration, we’re seeing a return to big investments in improving our capabilities to forecast, monitor, and observe,” said Kirtman, who is also director of the University of Miami-NOAA Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies. “One of the trickiest things for us is understanding how the ocean and the atmosphere interact. These new observations are going to help us do a whole lot better job at grasping and deciphering that critical exchange of heat.”

Kirtman is a key architect of the Subseasonal Experiment, or SubX, which combines multiple global models from entities like NASA and NOAA to forecast weather conditions three to four weeks ahead. He said the new Earth System Observatory could also aid scientists in determining the moisture content in soil, especially during spring and fall—two seasons of transition in the mid-latitudes that provide glimpses of what’s to come. “There’s a lot of local moisture recycling related to increased precipitation,” he explained. “So, it will also help with developing better rainfall forecasts. And we’re constantly seeking better estimates of rainfall, and satellites are the best way for us to do that.”

Brian Soden, professor of atmospheric sciences, expects NASA’s new mission concept to greatly impact his research. He uses observations from the space agency’s satellites to test and improve model predictions of how changes in climate impact weather events at a regional level.

“As the climate warms, the frequency of many types of extreme weather events such as heat waves, floods, and droughts will increase,” he said. “Satellites provide global observations of these events that can be used to improve our understanding of how they will change in the future.”

Brian McNoldy, senior research associate and tropical cyclone expert at the Rosenstiel School, who has been the tropical weather expert for the Washington Post’s Capital Weather Gang blog since 2012, answers questions about the 2021 Atlantic hurricane season.

Could NOAA’s forecast change as the season progresses?

Absolutely. Usually, any changes are minor adjustments, but as the peak months of the season approach, key environmental predictors come into sharper focus. NOAA will publish one more forecast in early August, prior to the core of the season. However, always remember that it’s not the overall level of activity that matters to a specific location. If a season had only one hurricane, and that hurricane makes landfall near your town, it’s a bad season for you.

NOAA has updated the statistics used to determine when hurricane seasons are above, near, or below average. Going forward, an average Atlantic hurricane season will have 14 named storms, seven hurricanes, and three major hurricanes. Why the adjustment, and how did the agency arrive at the new numbers?

This is a calculation made every decade. The climatology we were using was derived from the 1981-2010 period, and 1971-2000 before that. Now, we move on to the 1991-2020 period and the numbers changed. These “climate normals” are updated every decade by agencies around the world for lots of meteorological parameters. The reason for updating them is to keep the reference baseline representative of the current climate. If you don’t do that, then things like averages and anomalies start to lose their meaning.

Could climate change be one of the reasons for the increase in the number of storms in an average season?

It certainly could be, though it’s hard to say what the contribution is. We don’t expect a real increase in overall tropical cyclone activity in a warmer climate, but some studies have projected an increase in the fraction of storms that become really intense. In this specific case, the 1981-1990 period got dropped from the average, and 2011-2020 was added in its place. So, the previous and current averages both include 1991-2010. Since the 1980s were generally rather quiet and the 2010s were generally rather active, the noticeable jump comes as no surprise. In 2031, when we switch to using the 2001-2030 period, it’s entirely possible that the counts could come back down a little.

What is the Bermuda High, and what role did it play in helping to spare Florida from all the storm activity that occurred last season?

The Bermuda High or Azores High is a semi-stationary high-pressure system in the North Atlantic Ocean. Its exact position and strength vary, but it is the dominant steering mechanism for tropical cyclones in the Atlantic And it tends to be centered near the Azores but can extend westward to Bermuda. During the heart of the 2020 hurricane season, on average, the steering was such that the U.S. East Coast was relatively protected, not just Florida, while regions to the west and east of that saw heavier storm traffic. The bulk of the activity was directed westward into the Gulf of Mexico or western Caribbean Sea, and there were a few hurricanes that remained out at sea, well east of the U.S. Comparing last May to this May for what it’s worth, the Bermuda High is stronger this year and larger in extent. If that persists for the next three to four months, that favors storms staying longer in the deep tropics with tracks even more likely to enter the western Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico. But I wouldn’t hang my hat on that persistence forecast.

With recent hurricane seasons having powerful storms that inflicted catastrophic damage, could we eventually see a new category for hurricane strength and intensity created—a Category 6, perhaps?

The notion of a Category 6 hurricane has been around for decades, almost since the open-ended five-category Saffir-Simpson scale was introduced in the early 1970s. By peak wind speed, the top five strongest Atlantic hurricanes occurred in 1980, 1935, 1988, 2019, and 2005, so there’s not really a clustering of super-intense storms in recent years. A Category 5 hurricane requires sustained winds of at least 157 mph, and just under 2 percent of Atlantic named storms ever reach that threshold. So, to further stratify that tiny list does not have a lot of benefit, and even at the Category 5 rating, the expected damage is described as follows: “Catastrophic damage will occur: A high percentage of framed homes will be destroyed, with total roof failure and wall collapse. Fallen trees and power poles will isolate residential areas. Power outages will last for weeks to possibly months. Most of the area will be uninhabitable for weeks or months.” I don't know what else a Category 6 rating would add to that. Furthermore, the current rating system only relies on the peak wind speed found somewhere in the storm. It says nothing about impacts (rain, storm surge, etc.) or size (how large of an area will be affected). So, if anything, there’s some interest in a whole different scale of some sort.