Something seemed peculiar, at least to the thousands of storm-weary people in Louisiana who were riding out Hurricane Ida on Sunday afternoon.

Hours after the cyclone roared ashore as a dangerous Category 4 storm—destroying buildings and knocking out power to more than one million customers—the storm remained well organized instead of losing strength like most cyclones do upon making landfall.

“This was not entirely surprising,” said Brian McNoldy, a senior research associate and tropical cyclone expert at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science.

The phenomenon is known as the “brown ocean effect,” in which latent heat from extremely saturated soil mimics the moisture-rich conditions of the ocean, McNoldy explained. “South Louisiana, like South Florida, is flat and marshy. It’s only slightly different from the ocean, meaning that friction doesn’t increase too much, and there’s still some source of moisture,” he said, noting that about 20 percent of landfalling tropical cyclones experience the effect.

Hurricane Ida’s slow weakening was not the only intriguing aspect of the Atlantic hurricane season’s ninth named storm. It made landfall on the anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, which devastated New Orleans, killed more than 2,000 people, and became one of the costliest storms in the nation’s history.

“It was surreal watching Ida make landfall as a major hurricane in southeast Louisiana,” McNoldy said. “I remember watching Katrina’s landfall with the same level of anxiety 16 years ago. Not only did they occur on the same date, but they also made landfall just 40 miles apart. Both hurricanes tapped into the hot-tub conditions that characterize the Gulf of Mexico in late August, and both storms passed directly over a significant warm eddy in the central Gulf, which is a lobe of really deep warm water related to the Loop Current.”

“It was surreal watching Ida make landfall as a major hurricane in southeast Louisiana,” McNoldy said. “I remember watching Katrina’s landfall with the same level of anxiety 16 years ago. Not only did they occur on the same date, but they also made landfall just 40 miles apart. Both hurricanes tapped into the hot-tub conditions that characterize the Gulf of Mexico in late August, and both storms passed directly over a significant warm eddy in the central Gulf, which is a lobe of really deep warm water related to the Loop Current.”

But that’s about where the similarities end, he noted.

While Katrina was a larger cyclone, Ida was stronger—the former making landfall as a Category 3 hurricane (127-mile-per-hour peak sustained winds) and the latter as an upper-end Category 4 cyclone (150-mile-per-hour peak sustained winds). “Those peak winds only exist in a really small portion of the storm in the eyewall, yet are the entire basis of the Saffir-Simpson Scale’s category rating,” McNoldy said. “The category of a hurricane has nothing to do with rainfall and isn’t always too well-correlated with the storm surge either.”

At the time of their respective landfalls, the area of hurricane-force winds was about seven times larger in Katrina, said McNoldy. He noted that Katrina’s tropical storm force winds extended up to 230 miles from its center, while Ida’s extended as far as about 140 miles from its center.

And those parameters lead McNoldy to another metric for storm strength: Integrated Kinetic Energy, or IKE, which accounts for the energy of a storm’s entire surface wind field, from the center to the outermost tropical storm-force winds.

“At landfall, Katrina’s IKE was over three times greater than Ida’s, even though it was weaker in terms of peak wind speed,” he said. “This matters a lot for impacts. A larger storm means more places will be subjected to destructive winds, and higher IKE values correlate really well with storm surge generation potential. Katrina produced a record-breaking 28-foot storm surge in Mississippi. I’m certainly not trying to diminish the catastrophic impact that Ida had on the area, but the storm surge depths might end up being measured to be half of Katrina’s.”

McNoldy, who is also the tropical weather expert for the Washington Post’s Capital Weather Gang blog, answers other questions about Ida.

How did Ida intensify into a major hurricane so quickly?

Although Ida ended up intensifying at an extraordinary rate, it was fully expected to undergo rapid intensification (RI) over the Gulf of Mexico. In fact, in the very first forecast the National Hurricane Center made for Tropical Depression 9 (pre-Ida), they explicitly included RI, which is really rare—it’s rare to have such high confidence in something that is defined to be exceptional. RI is conventionally defined to be an increase in the peak sustained winds of at least 35 mph in a day. Ida’s peak winds increased by 63 mph in a day. The storm just took advantage of the ideal environmental conditions that existed. Unfortunately, those conditions existed right up through landfall.

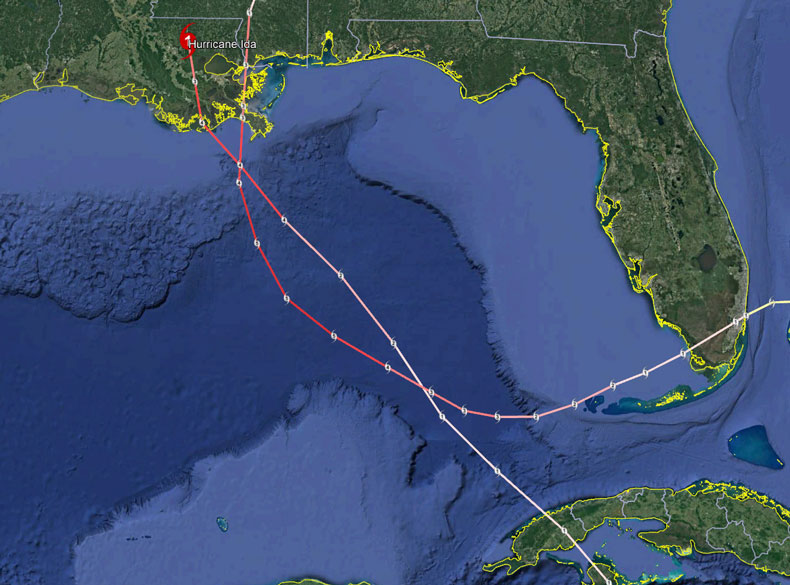

How do the tracks of the two storms differ?

Katrina made its first landfall right here in Miami as a Category 1 hurricane four days before its Louisiana landfall as a Category 3 hurricane. In between, it reached Category 5 intensity for 18 hours, then rapidly weakened as it approached land. Ida came into the Gulf of Mexico from the south, after making landfall in western Cuba as a Category 1 hurricane. Then, it strengthened during its 1.75-day journey across the Gulf, nearly reaching Category 5 intensity at landfall.