With five named storms already in the books, the 2021 Atlantic hurricane season is expected to remain above average. At least that’s what the latest forecast from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) seems to suggest.

Just as they have done for the past 22 years, forecasters at the agency’s Climate Prediction Center issued a midseason update to their annual hurricane season outlook, predicting 15 to 21 named storms, of which seven to 10 could become hurricanes, with three to five of those becoming major tropical cyclones.

NOAA’s initial forecast, issued last May, had called for 13 to 20 named storms, with six to 10 becoming hurricanes.

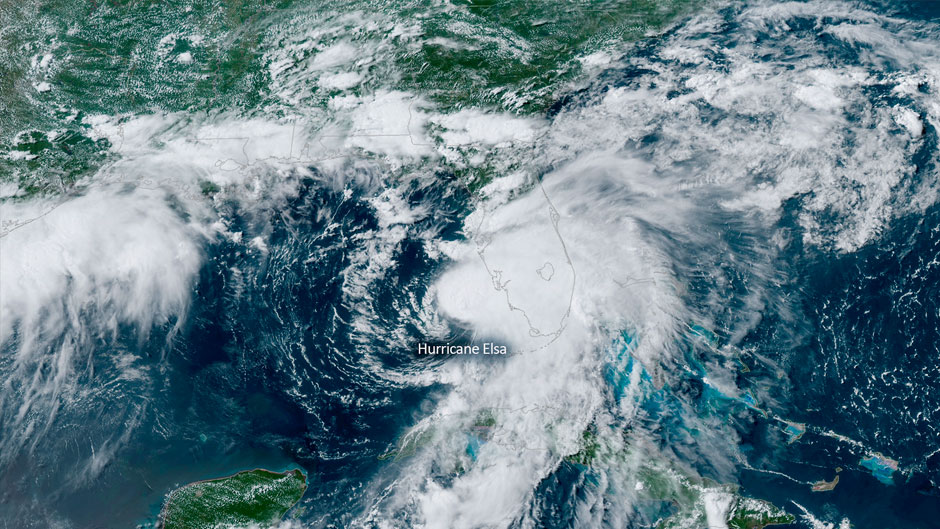

“There has not been a large change because the update also reflects activity that has taken place since the season began,” said Brian McNoldy, senior research associate and tropical cyclone expert at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, noting that the midseason outlook includes the five named storms that have already formed this season, including Hurricane Elsa, the earliest fifth named storm on record.

“Ocean temperatures are near average, or slightly warmer than average in some key locations, and there is a possibility that ENSO (El Nino Southern Oscillation) could trend toward the cool phase (La Nina) again later in the season,” McNoldy said. “It’s currently on the cool side of neutral. We tend to see enhanced hurricane activity in the Atlantic during La Nina.”

NOAA’s midseason update is invaluable, he said, as critical environmental parameters can change in the two months since forecasters issued the initial season outlook. “Sub-seasonal forecasts of things like ocean temperatures and ENSO have some skill but are not perfect,” McNoldy explained.

It was the late Colorado State University atmospheric scientist Bill Gray and his team who originated seasonal hurricane forecasts 37 years ago, issuing midseason updates to their forecasts from the very beginning. “The value of these updates was recognized immediately,” McNoldy said. “NOAA began making seasonal hurricane forecasts in 1999 and has issued midseason updates since then.”

McNoldy, who has been the tropical weather expert for the Washington Post’s Capital Weather Gang blog since 2012, answers more questions about the update.

How far out of the norm is the midseason hurricane outlook?

To put the forecast of 15 to 21 named storms, seven to 10 hurricanes, and three to five major hurricanes in context, the average numbers of those, using the 1991-2020 climate normal values, is 14, seven, and three. So, the low end of their range is about average. Furthermore, looking back through the reliable weather satellite era (1966-2020), there’s historically about a one-in-three chance that the storm counts will fall within those ranges, so they’re really not too far out of the norm.

Why is the beginning of the Atlantic hurricane season so quiet, and why do we see so much activity from August through October?

The Atlantic hurricane season officially spans June 1 through November 30 and is meant to encompass a large majority of the activity, not necessarily all of it. But even then, three of the six months are typically rather quiet: June, July, and November. In fact, about 3/4 of the activity occurs during just two months, from mid-August to mid-October. There are several atmospheric and oceanic ingredients that come together during August, September, and October to create that abrupt surge and decay of activity. The African Easterly Jet is found in the tropical belt of continental Africa and is most vigorous during these months. That jet regularly breaks down to form waves, and those waves are the seedlings of most hurricanes and especially major hurricanes. Speaking of Africa, Saharan air/dust outbreaks are common in June and July, and they are great at suppressing tropical cyclone activity, but they start to dwindle off as we get into August. Ocean temperatures reach their warmest during the peak months of hurricane season, which isn’t a coincidence. And vertical wind shear, or the difference between low-level winds and upper-level winds, typically is lower during these months, and that favors the development and intensification of tropical cyclones.

We saw a lot of storm activity in the Gulf of Mexico last season. Was there a reason for that, and can we expect to see the same this year?

In hindsight, there was a blocking pattern over the U.S. East Coast during the prime of hurricane season on average, which helped divert storms south of Florida and into the Gulf of Mexico. This year, at least during the past month, that same pattern isn’t present, so the whole Gulf Coast as well as Florida and the Southeast U.S. is a bit more open to hurricane tracks. That can evolve, of course.