Arthur Dunkelman used maps, charts, books, and artifacts from the Jay I. Kislak Collection of the Early Americas to provide a virtual tour titled “Icebound: The J.I. Kislak Polar Collection,” presented on Thursday as part of University Libraries Deep Dives Special Collections lunchtime series.

The tragic tale of Sir John Franklin epitomized the enormous and oftentimes fateful appetites of those who sought fame and glory in exploring the Terra Incognita, as the Greeks referred to the vast polar regions at the ends of the earth.

“Of all the renowned explorers none achieved as much high fame as Sir John Franklin, a man destined to cause a crisis about the meaning of Arctic exploration,” said Dunkelman, curator of the Kislak Collection.

Displaying items from the collection, the curator noted how in 1845, Franklin, then 59, embarked on his fourth Arctic expedition with two ships and 128 men aboard. Both ships became trapped in ice in the Canadian Arctic’ Franklin died on board; and the crew set off in sleds, all to eventually die from scurvy, starvation, hypothermia, or lead poisoning.

England launched 39 separate rescue missions, but it wasn’t until 11 years later that it was determined that Franklin had died and the last of the cannibalized corpses were discovered. The actual ships were not located until 2014—175 years later, Dunkelman noted.

Despite the tragic misfortune, Franklin himself was deemed a hero and his expedition inspired a range of newspaper reports, stories, and even a play, “The Frozen Deep,” in which Charles Dickens appears as an actor.

Dunkelman noted the ultimate failing of most of the explorers, who shunned the wisdom and practices of indigenous peoples who managed to survive in the inhospitable terrain of the hinterlands.

“It is possible to live in the Arctic. But steeped in racial prejudices, most polar explorers refused to imitate indigenous ways of traveling, hunting, eating, and staying warm, and suffered the consequences unto death,” he pointed out.

Little accurate information about the Arctic was known until the 17th-century when ambitions to discover Northeast and Northwest Passages to Asia prompted exploration, he explained.

“At the beginning of the 19th century the largely unexplored Arctic captured the public’s imagination—the prospect of an open polar sea made the quest for a Northwest Passage credible,” Dunkelman said. England sent ships sailing north for decades fueled by ambitions to discover a shorter water route between Europe and Asia—a route that would dramatically expand global trade.

“Yet by mid-century—and after 250 years of lost lives and treasure—it became increasingly evident that there was no Northern Passage to the ‘wealth of the Indies,’ ’’ Dunkelman said. “Conversely, the Antarctic held little fascination for early explorers. And the vastness of the continent was not charted until the middle of the 20th century, when aerial observation made mapping possible.”

The Antarctic—the coldest, driest, and windiest continent with the highest elevation on earth—was so remote, he explained, that it was even beyond the imagination of the early Greeks who, aware that there must be two ends of the planet, simply termed it “the other Arctic.” Yet while this polar desert receives less than 8 inches of precipitation a year, it holds 80 percent of the freshwater reserves. And if it were to melt, sea levels would rise by 200 feet.

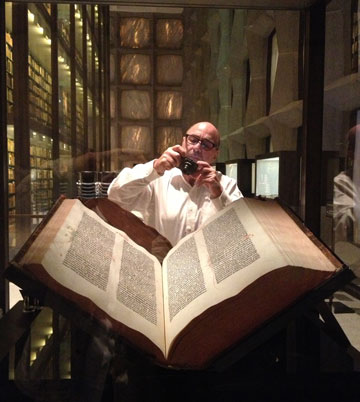

Dunkleman joined the University as curator after spending more than 24 years working closely with Jay I. Kislak—prominent collector, philanthropist, and Miami resident for more than 60 years—to build a collection of rare books and historic artifacts focused particularly on Florida and the Caribbean, exploration, navigation, and the early Americas.

A large number of the artifacts highlighted in Dunkelman’s presentation are displayed in the Gallery at the Kislak Center.