Before this spring, third-year law student Mischaël Cetoute said he had never considered taking a walk barefoot in the rainforest. But when Cetoute signed up for a class on coastal management that sent him to an island off the coast of Chile, he recognized he was in for an adventure.

Despite his reservations, Cetoute said he is glad he embraced the experience, because the “Baño de Bosque,” or guided rainforest meditative walk, helped him connect with the picturesque natural surroundings. It also set the tone for the coming week.

“Initially, I was very apprehensive about the idea, but I really appreciated that experience and would love to do it again in the future,” said Cetoute. “It made me realize, ‘Wow, there’s this great opportunity to engage with one the world’s most unique ecosystems.’ ”

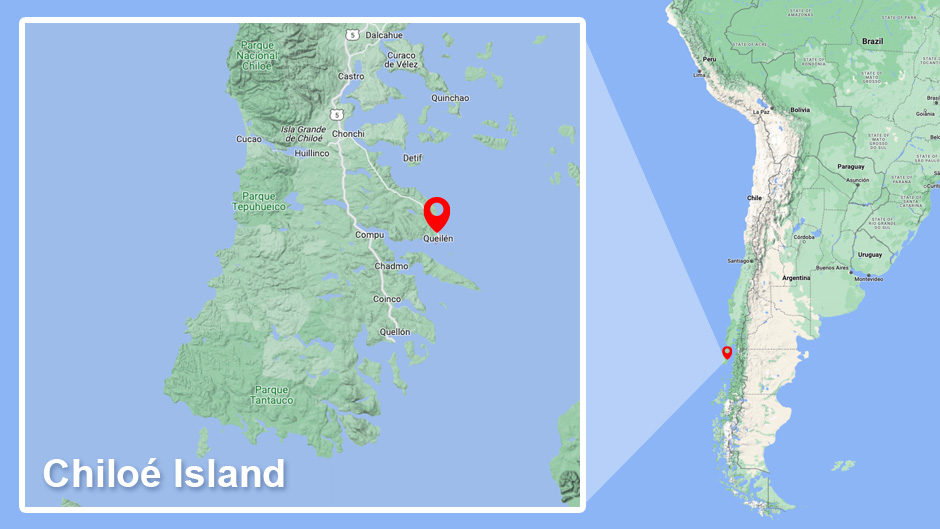

He joined 19 other students on an unforgettable excursion to Chiloé Island, about 760 miles south of Santiago, Chile, as part of a University of Miami class called “Fieldwork in Coastal Management.” Led by Daniel Suman, a professor of environmental science and policy and adjunct professor of law, graduate students from the School of Law and the Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric, and Earth Science spent spring break living in four cabins of an ecotourism lodge called Comarca Contuy, which is also a working farm. It is the third time Suman has taken a class to Chiloé Island, and as part of their final projects, the students must explore one aspect of the region’s sustainable practices—including its legal regulations.

“I want them to get an understanding of environmental problems and challenges in Chiloé and to understand how the government is managing those issues,” said Suman, an international expert in the development of marine protected areas. “But I also hope they gained an appreciation for this unique ecosystem and island and got a chance to compare Chile’s national culture with ours in the United States, in terms of environmental management.”

Throughout the week, the group ventured around Chiloé Island—located in the temperate Patagonian region—and gained firsthand knowledge of a place they had only been learning about in class. Suman coordinated a packed schedule for the students, including guided nature walks, a boat tour of the island (where students observed local wildlife like Magellanic penguins and small Chilean dolphins), discussions with rangers in Chiloé National Park, and conversations with local Indigenous people who are part of the Huilliche ethnic community. One day, they even visited a base of the Chilean Maritime Authority (similar to the Coast Guard), and on other days they toured two of the island’s nearly 100 aquaculture facilities—AquaChile, which grows, packages, and exports farmed Atlantic salmon, and St. Andrews, which grows, processes, and sells mussels to more than 70 countries.

Chris Malanuk, a Rosenstiel School student in marine conservation, served as a teaching assistant for the class. Malanuk, who eventually hopes to go into environmental law, said the time in Chiloé was extremely eye-opening for him, particularly the tours of the two aquaculture facilities. At the St. Andrews facility, everyone had to wear full gowns, and the group had to change boots in between the processing and packaging areas to ensure there was no cross-contamination.

“This trip really added to my perspective about the many complications in environmental policy and law, especially with large industries like aquaculture trying to adhere to a host of regulations,” he said. “From books and podcasts, I’ve heard a lot of criticism of this industry and its sustainability, but what we saw left me with a better impression. I saw how efficient and organized they were, as well as sanitary, and it was really impressive.”

Amy Feltz, a marine biology master’s candidate studying fisheries management, agreed that the aquaculture tours were one of the most interesting parts of the trip. But she also loved learning about eco-centric traditions, like how Chiloé residents try to diversify their farming, so it is less harmful to the Earth. The Chilean government agency, CONAF, also promotes sustainable forestry harvesting—by only using trees that are dying or deformed—for firewood and construction of furniture and homes.

“It was such a great experience overall, and it was both interesting and beneficial to visit aquaculture facilities in a different part of the world,” said Feltz, who took advantage of her Spanish skills to learn more about the area from the Chilean owners of Comarca Contuy. “This trip improved my worldview quite a bit and made me really interested in working internationally.”

Cetoute, who plans to go into real estate law, took the class to better prepare himself for working with South Florida developers, so that he can understand the implications of legal decisions on the natural environment. But while in Chiloé, Cetoute said he realized that protecting South Florida’s environment is critical to the future of development.

“This class helped me to understand that Miami’s economy is entirely dependent on our beautiful natural environment, and therefore, protecting our coasts and wetlands is necessary for the long-term financial success of any development,” he added.

Cetoute and Feltz were also fascinated by Chile’s leadership in environmental protection, including its network of preserves and national parks that make up more than a fifth of Chile´s land area and 41 percent of the nation’s territorial waters. This broader viewpoint is exactly what Suman hopes his students gain from the experience.

“Moving away from where we are in the U.S. and seeing how a different country operates helps to create international citizens that have a respect and appreciation for the rest of the world,” Suman said. “And I think that is so important.”