The view from the passenger window of the turboprop seaplane always had been the same: miles and miles of clear blue water as the aircraft made the 30-minute flight from Key West to Dry Tortugas National Park.

Maritime archaeologist Joshua Marano had taken the short flight on numerous occasions, traveling to the park’s historic Fort Jefferson to assist in restoration projects.

But one day in the summer of 2016, as the seaplane descended for an aquatic landing, Marano saw something unusual: an L-shaped pattern of dots below the water.

“Very early in my archaeological career, I was taught that you don’t find patterns or rigid shapes in nature,” said Marano, an adjunct professor in the Exploration Sciences Program at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric, and Earth Science. “Usually, that indicates there’s some kind of manmade structure.”

Could the peculiar dots have been navigational aids from a bygone era? Marano wasn’t sure.

Once he returned to the mainland, he did a little sleuthing, learning that the area was a submerged island near the 100-square-mile park where a 19th-century quarantine hospital and cemetery once may have been located.

“We still needed to get in the water and get eyes on it,” Marano said. So, he promised himself to one day explore the site with a team of divers. Hurricane Irma and a year’s long active-duty deployment as a Coast Guard reservist during the height of the pandemic would delay that plan.

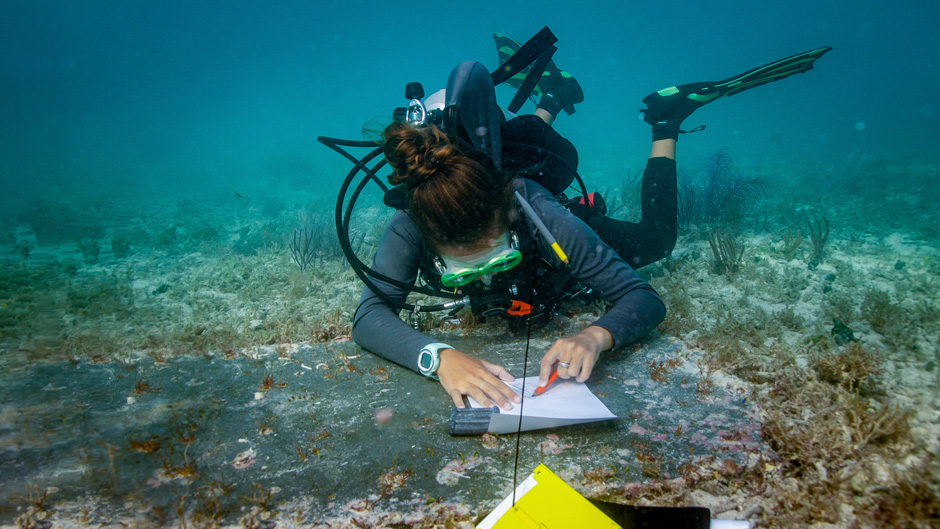

Then, one day in mid-August 2022, Marano finally got the chance. Swimming parallel lines from north to south over the shallow area, and using a GPS tracker to maintain their course, he and two other divers discovered the remains of the quarantine hospital and cemetery he had researched and read about in official records. The mysterious dots turned out to be the remnants of pylons that made up the hospital’s foundation—the space between them matching to a tee the measurements of the hospital Marano had located in records.

The national park service only recently announced the discovery to coincide with preservation month, which is celebrated in May.

Marano and former Rosenstiel School graduate student Devon Fogarty, who played a key role in the discovery, recounted the monthslong process that went into finding the hospital and cemetery.

“On the day we surveyed the site, we counted 25 pylons in all,” Fogarty recalled. “We were preparing to return to our boat, when I noticed a rectangular-shaped patch of seaweed.”

With Marano and another diver closely following behind her, Fogarty swam over to the patch of seaweed and discovered that it covered a gravesite with a headstone bearing an inscription they could only partly make out. They deciphered what they could, then left. The next day, they returned to the watery grave with ordinary kitchen sponges, clearing away the rest of the debris on the headstone until they could read the entire engraving. “JOHN GREER. Nov. 5. 1861,” it read.

For Fogarty, finding the grave was a major coup of her still fledgling career in marine archaeology. But her work on the project was just beginning. The team wanted to know more about John Greer. Was he a soldier or a civilian? And how did he die? Fogarty was tasked with finding the answers.

She started by reading up on Fort Jefferson’s past. She knew that, in addition to being used as a military prison during the American Civil War, the fort also served as a naval coaling outpost, lighthouse station, naval hospital, and safe harbor for military training.

As the population of the fort swelled with military personnel, prisoners, enslaved people, engineers, support staff, laborers, and their families, the risk of communicable diseases, particularly mosquito-borne yellow fever, increased. The quarantine hospital, the remains of which she helped discover, had been used to treat yellow fever patients.

Major outbreaks of other diseases exacted a heavy toll on those staying at the fort, killing dozens throughout the 1860s and 1870s, according to Fogarty.

Some of those who perished were interred in the cemetery. While most of them were military members who were serving or were imprisoned at the fort, several others were civilians. And one of those civilians, she discovered, was John Greer.

Fogarty’s investigation of him took her all the way to the National Archives Museum in Washington, D.C., where, over the course of two days, she learned that he was a white laborer who worked as a scaffolder at the fort. “I located his pay stubs,” she said. “He’s actually still owed some money for the work he did there.”

But that is the extent of what she was able to dig up on Greer. “We have no idea of how old he was or where he came from,” Fogarty said. “We’re theorizing that he died of an infectious disease and hadn’t sought treatment, or he may have died unexpectedly. He did a very dangerous job compared to others who worked at the fort.”

Greer’s headstone is made from a slab of greywacke, the same material used to construct the first floor of Fort Jefferson.

The National Park Service has no plans to excavate the site but will continue to monitor and conduct surveys of the submerged island, which over time has been eroded by sea level rise and hurricanes. “We advocate for in-situ preservation, leaving things in place and undisturbed,” said Marano, noting that their discovery is protected by federal law. “The idea is to preserve and protect resources for the betterment of this and future generations.”

They hope to learn more about Greer. “Hopefully, as the public interest grows in this project, people will share family letters that they may have had in their keeping and didn’t really think were important,” said Fogarty, who is now a doctoral student at the University of South Florida. “We would love to find Greer’s closest living descendants and be able to make that connection to modern people.”

Fogarty, who, like Marano is a Coast Guard reservist, got involved with the project through the Rosenstiel School’s Underwater Archaeology Program, which she credits for improving her research skills.

Frederick “Fritz” Hanselmann, a faculty member in the Department of Environmental Science and Policy, who directs the program, said the discovery “demonstrates the opportunities that are available for students to work alongside professionals and to conduct cutting-edge archaeological research that sheds light on our shared past.”

He added that Fogarty’s “enthusiasm for archaeology and history coupled with a very strong work ethic and a desire to continuously learn figured largely into her success on this project.”

For Marano, the discovery is “the most remarkable” of his career. As a little boy, he became intrigued by marine archaeology after buying a map of shipwrecks while vacationing with his family in the Outer Banks. And as a student at East Carolina University, he explored Queen Anne’s Revenge, the early 18th-century pirate ship commanded by Blackbeard and discovered on the seabed near Beaufort Inlet, North Carolina, in 1996.

“I’ve found some cool stuff during my time as a marine archaeologist, but this takes the cake as the coolest,” Marano said. “Archaeology is not like the Indiana Jones movies, and underwater archaeology is nothing like [the 1985 movie] ‘The Goonies’ or ‘Scooby-Doo,’ where you have shipwrecks standing up and skeletons at the helm. But this [the quarantine hospital and cemetery] is a career-defining discovery.”

High tides, rising sea levels, and hurricanes continue to erode Dry Tortugas National Park, which is why “it’s important to investigate and document such sites,” Marano said. “We’re literally in a race against time.”