Its 5,000-mile journey now complete, a massive plume of dust that originated in the Sahara Desert has reached South Florida.

The dust, known as the Saharan Air Layer (SAL), blanketed skies over Puerto Rico on its journey east. The plume was expected to spread across Florida and bring drier conditions after several days of precipitation. Forecasts called for the plume to then break apart and move into the southeast Atlantic, with Georgia and South Carolina perhaps experiencing some effects.

But the outbreak won’t be the last.

“We’re entering the peak season for such outbreaks,” said Jason Dunion, a meteorologist with the University of Miami Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies and the Hurricane Research Division of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, who has studied Saharan dust’s impact on tropical cyclone formation.

SAL activity typically ramps up in mid-June, peaking from late June to mid-August before it begins to subside after mid-August. At its height, individual SAL outbreaks emerge from the coast of Africa every three to five days, reaching farther to the west and covering vast areas of the Atlantic.

It is legendary atmospheric scientist Joseph Prospero, who is now an emeritus professor at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric, and Earth Science, who discovered the Saharan Air Layer. Decades after that discovery, the topic of Saharan dust never gets old for Prospero, who is known as “the father of dust.”

“The phenomenon has been well established to have an impact on many aspects of our lives—from our climate and human health to our safety in the sense of reduced visibility, which can complicate aircraft traffic and driving conditions on roads,” he said.

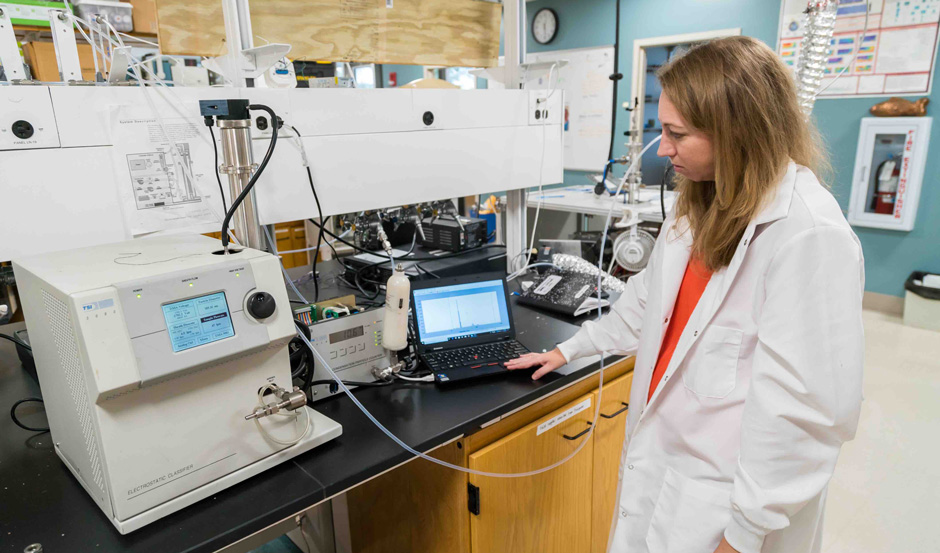

Nearly 60 years ago, Prospero founded the Barbados Atmospheric Chemistry Observatory, a specialized lab on the east coast of the island that documents the transport of African dust to the Caribbean Basin. Cassandra Gaston, an associate professor of atmospheric sciences, now heads the facility.

The SAL, Prospero noted, also impacts the biogeochemical cycles in the ocean. “So, it’s proven to have a widespread and complex impact on the environment,” he said. “And it’s satisfying to me to see that this subject has been taken up and extensively studied by many groups over the past decades.”

With University of Miami experts weighing in, here’s what to know about the Saharan Air Layer.

Saharan dust travels thousands of miles to reach the U.S. How is it able to travel so far? What drives it?

The dust is transported far from Africa due to its altitude several kilometers above the ocean and due to prevailing winds that push the dust westward. The dust transport to Miami and other parts of the U.S. is a summertime phenomenon because the sun can heat the deserts in Northern Africa, causing dust to be lofted in a hot air mass known as the Saharan Air Layer (SAL). The reason the dust is transported at altitude is because the SAL is hotter than the air layer above the ocean. When the SAL reaches the west coast of Africa, it encounters a colder air mass and this hot air rises. As the dust is transported westward, it sinks a bit in altitude along the way, causing regional impacts in both the Caribbean as well as the south and southeastern United States.

—Cassandra Gaston, associate professor of atmospheric sciences, Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric, and Earth Science

Do clouds play any role in the transport of the Saharan dust that reaches the U.S.?

Clouds don’t play much of a role in the transport of the dust. The same weather patterns that encourage the dust transport displace moist, tropical air with drier and warmer continental air, initially above the atmospheric boundary layer. This warm, dry, dusty layer acts to suppress deep convection. So, even though the dust on its own can cool the surface by blocking sunlight, because the cloud cover is often also reduced, dusty days in South Florida often feel hot and muggy. Over the Atlantic Ocean, the reduced cloud cover means less of the dust is removed by rain en route.

—Paquita Zuidema, professor and chair of the Department of Atmospheric Sciences, Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric, and Earth Science

When do the largest dust events occur, and why are some years worse than others?

The largest dust events occur each year in the summer. One of the reasons some years result in more dust transport than others is due to changes in the amount of precipitation in Northern Africa. During drier years, when Northern African deserts receive less rainfall, more dust is transported westward and impacts us here in South Florida. Other factors include wind and pressure gradients that drive circulation patterns and impact dust transport patterns.

—Cassandra Gaston

What are some of the latest research findings in this area?

My lab has recently completed several field campaigns at the University of Miami’s Barbados Atmospheric Chemistry Observatory, which is located on a Caribbean island that receives most of the dust transported from Africa. The campaigns were conducted in collaboration with the University of Wisconsin and partners from the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory and other research institutions. Thus far, we are finding dust transport events that are some of the largest we have ever measured on the island as well as major intrusions of smoke from crop burns in Northern Africa. We are currently analyzing our results to determine what the impacts are for air quality in the Caribbean and U.S.

—Cassandra Gaston