For three weeks, I joined Al Uy and Floria Mora-Kepfer Uy for an immersive field research course in the Solomon Islands titled “The Origins, Ecology and Conservation of Insular Diversity.” Uy, who is a biology professor and the Aresty Chair of Tropical Ecology in the University of Miami College of Arts and Sciences, and Mora-Kepfer Uy, a former assistant professor at UM, have been taking undergraduates with them to the Solomon Islands for a few summers to learn about ecology, evolution, and conservation through field experiments and observations.

We stayed on Makira Island, nestled among the eastern Solomon Islands in the South Pacific Ocean. We lived in a small subsistence village and grew close with our gracious hosts. Each night, we slept in a lodge made entirely of bamboo, palm, and other local trees.

Makira is the only island in the archipelago unconnected by land to any of the other major islands during past ice ages, which makes it a hotbed for many unique species not found anywhere else on earth. Nearly every day, we went on hikes to observe the island’s rich biodiversity. During these hikes, we took notes about natural phenomena we observed, as well as detailed accounts of all the birds we discovered, such as the gorgeous eclectus parrot, and endemic birds such as the Makira honeyeater and the Solomon sea eagle. These notes were later organized in a field journal.

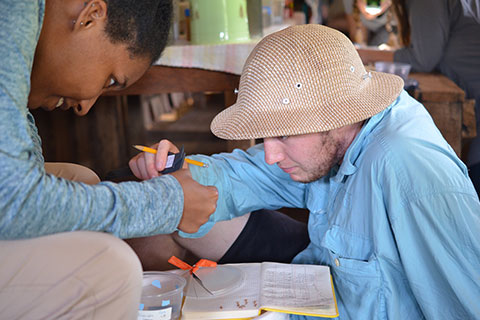

We also completed two group research projects and one individual project during the course. The projects encouraged us to study an array of animals in different habitats, and focused on different fields of animal biology, such as behavior, ecology, environmental science, and marine science. One group project studied the behavior of ghost crabs and examined how they camouflage themselves in response to the color of the sand. In particular, we tested whether it would take longer for the crabs to burrow under the sand if the sand’s color contrasted with their own shell. A second group project studied weaver ants’ territorial behavior. Weaver ants are aggressive to defend their colony, and can identify their own members, as well as intruders, by chemical signals and pheromone trails.

For my individual project, I focused on sea urchins, and how different types of pollution impact their populations. My results show that there are a low number of urchins on coral reefs without a direct source of pollution. At polluted sites, the type of pollution had different impacts. For example, at a site adjacent to a logging port and road, where lots of silt and eroded soil are dumped, there were no urchins. On the other hand, lots of urchins were found next to the center of the village, where lots of human waste, food waste, and animal waste enters the sea. This suggests that pollution involving lots of silt and sediments is harmful for sea urchins, while nutrient-rich pollution can benefit the urchins. This is an important research topic because there have been scenarios in which too many or too few sea urchins can be detrimental to a coastal marine ecosystem. Other students’ projects examined the rescue behaviors of sweat bees, social behaviors of butterflies, and how colonial tent spiders arrange their colonies.

We spent a great deal of time with the local residents, including playing with the kids in the village, spending time searching for ants, or eating meals. Al and Floria have developed a special relationship with the Solomon Islanders, and have worked with them to establish a conservation area. One day, we had a ceremony with members of different villages to start the Yato Conservation Area. With proper management in upcoming years, future success could lead to it becoming a national park, or even a world heritage site.

Thanks to a National Science Foundation grant, which funded our trip, this program allowed us to visit an amazing part of the world with lots of amazing, diverse fauna to study. The people there were incredible, and we were very fortunate to go to such a remote place where most people don’t have the opportunity to study. My passion for ecology and conservation biology attracted me to this experience and I am so glad I was able to do true field work, with the opportunity to possibly get my research published in the future.

To learn more about study abroad programs through University of Miami, visit the Study Abroad website at https://studyabroad.miami.edu/

Peter Aronson is a rising junior studying marine science, biology and ecosystem science and policy at the University of Miami.