The current shortage of semiconductor chips that is disrupting the auto industry in the United States and around the world—while highly problematic for workers—is not a result of supply chain malfunction, but instead is a consequence of the economics of chip-making and the resulting supply chain design, according to Hari Natarajan and Alex Niemeyer, both Department of Management faculty members in the University of Miami Patti and Allan Herbert Business School.

Natarajan, an associate professor and academic director of the Global Executive MBA program, and Niemeyer, a professor of professional practice, team-teach a class on supply chain analytics. Natarajan focuses on theory and Niemeyer, former global leader of the supply chain practice of management consulting firm McKinsey & Company, lectures specifically from a practice perspective.

“When these huge demand surges occur, in this case due to the pandemic, it exposes what a supply chain is built for—normal availability, not for extreme versions,” explained Natarajan. “Starting with the toilet paper shortage last March, it’s highlighted the idea that we need to be prepared to some degree for these disruptive events—but this doesn’t mean we’ll meet all the demand all the time.”

Niemeyer emphasized that in terms of the shortage of chips affecting the auto industry, nothing is broken, it is simply a demand and supply mismatch in an industry that cannot respond quickly.

“What we see here is a supply chain that was optimized for certain things and then a number of severe external shocks occurred that caused a disruption,” Niemeyer explained. “If you had known these shocks were going to come, then the disruption would have been entirely foreseeable—but it was so unexpected that it was too expensive to prepare for.”

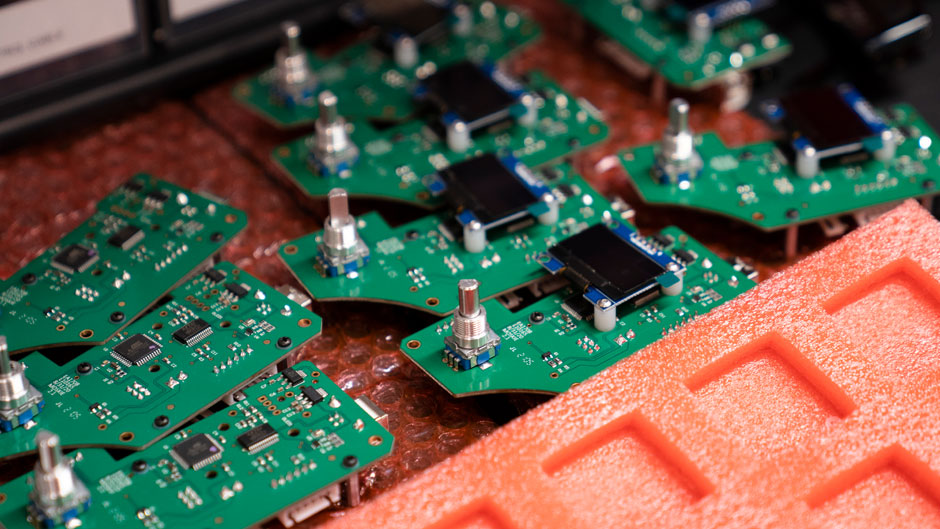

Chips, and lots of other semiconductors, have been traded as global commodities for the past 30 to 40 years, he pointed out. They are extraordinarily expensive and capital intensive to produce and made in plants that take years and billions of dollars to build.

Because of the inflexibility on the manufacturing side, the chips are not warehoused or inventoried in large quantities, they behave similarly to other products and industries—shipping, oil, steel, cement, among others—by responding to market fluctuations with shortages and price increases, Niemeyer noted.

Natarajan described supply chains as “vehicles that seek to ensure that supply meets demand.” He, too, pointed to the “phenomenally high capital investment” and the three-to-five-year time frame that would be required for major semiconductor manufacturers, such as TSMC in Taiwan, to build new facilities to ramp up production.

Niemeyer noted that auto manufacturers did what they were supposed to when the pandemic hit—they reduced their orders for chips—anticipating a downturn in demand. Yet as the economy, buoyed with stimulus funds, turned the corner and consumer demand increased, the auto industry hit a wall.

The same semiconductor firms that supply the auto industry also supply tech firms such as Apple, Samsung, and Sony. Yet the demand from the tech side is far greater—78 million cars per annum compared to billions of cell phones, laptops, etc.—and the more advanced chips required for tech products yield a better price and profit margin.

“If I’m at TSMC, my priority customers are Apple and Qualcomm, not Ford and VW or the other auto manufacturers,” said Natarajan. “The consumer electronic firms have more sway and pay more as well. So, you don’t see shortages being reported by Apple iPhones because they can get the semiconductor chips that they need.”

And as demand for autos dropped with the onset of the pandemic, demand for tech goods exploded with more people working from home and buying phones, laptops, and other products.

“Demand has skyrocketed for these tech products, and the auto industry locked itself in by making—at the time—a sensible decision,” Niemeyer explained.

“It will take some time, but it will balance back out,” he said. “Demand will come down again, and even if not, capacity will be built and catch up.”

Auto manufacturers have little leverage in their negotiations with suppliers because of the competitive pricing differential. They’re limited, too, by the specialty pockets requiring significant research and development and know-how that have emerged, according to Natarajan.

He identified three semiconductor pockets: TSMC manufacturing in Taiwan; ASML Holding in the Netherlands, which produces photolithographic machines to mass produce patterns of silicon; and the materials area in Japan, which yields some 50 percent of the minerals and metals needed for chips.

“It’s not possible to think you can redesign the supply chain,” explained Natarajan, adding that in terms of scale “it’s hard for a small player to emerge.”

In highlighting the “huge impact” that geopolitical tensions or forces have on globalization and, specifically on industries such as semiconductors, he posed the notion of a potentially new U.S. tariff on China.

“That would be a huge problem because there’s no easy way to resource the components coming from there,” said Natarajan, noting also that in recent years the U.S. has blacklisted several Chinese companies—Huawei, ZTE, among others—citing national security concerns.

Yet one thing developed countries such as the United States can do is to legislate policy that provides for “minimal viable capacity” to address national security concerns and help to ensure that critical industries are not affected, Natarajan explained. He noted that TSMC is exploring the possibility of setting up foundries in Arizona.

In this same regard, he pointed to the fact that the Biden administration in mid-February initiated a process for government divisions—departments of commerce, defense, and others—to generate reports within 100 days that provide strategies for safeguarding critical industries.

Those reports are due May 15.

“Previously, after the Ebola crisis (2014-16), there was some focus on this issue of strategic stockpiling, but we lost sight of it,” Natarajan said.

“What this pandemic has done is brought a whole new focus on the idea of being prepared for extreme situations,” Natarajan added.