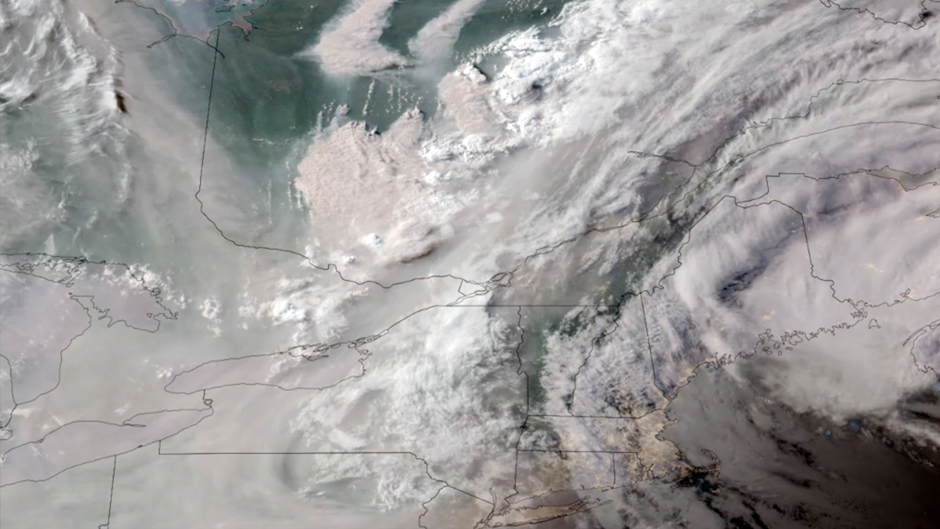

It is a dubious distinction New York City would undoubtedly rather live without. By midafternoon on Wednesday, the Big Apple ranked No. 1 among cities with the world’s worst air quality, with smoke from raging wildfires in Canada to blame.

The smoke has blanketed the city’s skyline, and it also has smothered much of the Great Lakes region and parts of the northeastern United States and reached as far south as South Carolina. This has prompted health alerts and air quality warnings impacting more than 75 million United States’ residents.

Television newscasts of the hundreds of fires burning in Canada and of the smoke drifting to parts of the U.S. are unsightly images. But worse, it could be a public health crisis of mammoth proportions, warned University of Miami public health, climate, and aerosol scientists who track and study the impacts of air pollution.

“When fires of this magnitude burn, the emissions are not confined to areas where the fires occur. They move across tremendous expanses depending on wind and other atmospheric conditions,” said Naresh Kumar, a professor of public health sciences at the Miller School of Medicine. “People with allergies, COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease], cardiovascular disease, and asthma are most at risk. But even healthy people can be in danger. Suddenly, they become confined to their homes, and their normal routines are disrupted, which could initiate conditions such as stress.”

Pratim Biswas, a renowned expert on aerosol research, dean of the College of Engineering, and one of the founding members of the Center for Aerosol Science and Technology (CAST), said people need to protect themselves from the smoke, which has many harmful chemical constituents.

“The best way to protect yourself if you have to go outside is to wear a filter mask,” said Biswas. “One of the best is the N95 mask, but anything is better than nothing. So, the surgical masks may be good if that’s all you can find. If you are immunocompromised or have asthma, it could trigger serious conditions, so those individuals should definitely be masked.”

Whenever investigating an aerosol—any particle suspended in a gas—scientists must consider its size, concentration, and chemical composition, Biswas noted. Aerosol scientists and engineers, including members of CAST, have access to a wide range of instruments such as aerosol mass spectrometers that enable them to accurately determine what is circulating in the ambient atmosphere.

“These particles are very small, and their size is in a range where if you inhale it. It might penetrate into your lungs,” he said. “That much we know, though their exact size varies. Also, the concentration [how much] is important, and the third thing is the chemical composition.”

The smoke from Canada’s fires contains a dangerous mixture of gaseous and particle pollutants, according to Cassandra Gaston, an associate professor of atmospheric sciences at the Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric, and Earth Science.

“Recent studies have pointed out that smoke particles from fires contain quite a bit of material that’s toxic when inhaled, so this is very concerning,” said Gaston, who along with Kumar, is also a member of CAST. “The EPA monitors, regulates, and issues warnings based on concentrations of particles in the atmosphere, and a lot of those regulations come down to the size [of the particles]. The smaller particles are more hazardous to health, and smoke particles do tend to be in the smaller particle size range.”

Gaston, who directs an atmospheric chemistry observatory on the Caribbean island of Barbados that monitors Saharan dust particles across the Atlantic Ocean, pointed out that not all small particles are the same.

“They’re made up of different chemical components, depending on where they come from,” she explained. “Smoke particles tend to have quite a few toxins associated with them. It is very worrisome that we’re seeing such high levels. When we think about wildfires or dust or pollution, it’s easy to say: ‘Well, that’s happening in another part of the world, so it’s not our problem.’ But as we’ve observed from wildfires and from Saharan dust, atmospheric transport is great at bringing air pollution from one part of the world to another very, very quickly.”

Chang-Yu Wu, a professor and chair of the Department of Chemical, Environmental and Materials Engineering, was one of the first aerosol researchers to find evidence that COVID-19 traveled through the air, changing the course of safety guidelines during the pandemic.

Wu said that particles released into the air from wildfires often contain aromatic hydrocarbons, which in high concentrations—like in the aftermath of the twin towers collapse in Manhattan on Sept. 11, 2001—are known to cause cancer. The smoke from the Canada wildfires also could impact future weather, he said.

“When you have a wildfire burning,” Wu said, “it releases a lot of biological and chemical materials into the atmosphere, which also affects the climate. For example, these particles can absorb and scatter sunlight coming to the earth with this wildfire smoke. So, that can affect the temperature, moisture distribution, and precipitation patterns,’’ he added.

“Often, too much smoke rising into the air will prolong drought conditions because the moisture remains trapped in the atmosphere instead of precipitating as rain,” Wu continued.. “This shows that besides the health impacts, these wildfire particles affect the moisture in the atmosphere, which in turn influences our climate.”

Wildland firefighters battling Canada’s blazes face a host of problems of their own, said Umer Bakali, a doctoral candidate in biochemistry and molecular biology, who conducts research on carcinogens to which those firefighters are exposed.

“Wildland firefighters’ respiratory health is especially at risk because, unlike structural firefighters, they usually don’t wear self-contained breathing apparatuses,” said Bakali, who is part of Sylvester Comprehensive Cancer Center’s Firefighter Cancer Initiative. “The tanks weigh them down, and it becomes too demanding from a cardiovascular standpoint to wear them, especially when they’re out in the wilderness and covering a lot of ground.”

With a warming planet, and the West Coast fire season getting underway, experts said we can expect more of these massive air pollution events.

“The current trend is more frequent wildfires with more intensity as a result of climate change,” Wu said. “And even air pollution produced from wildfires in the western states often gets transported east across the country annually.”