The conditions couldn’t have been better for sex on the reef: warm water and a full moon over Miami.

Liv Williamson and a team of fellow marine biologists donned diving gear and plunged into the nighttime waters off the coast of Key Largo, hoping to catch the “big event” as it unfolded.

It was a late July Wednesday, and she and the other divers had been submerged for nearly an hour. Then, just past 10 p.m., it happened. “Amazing,” Williamson, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, described it.

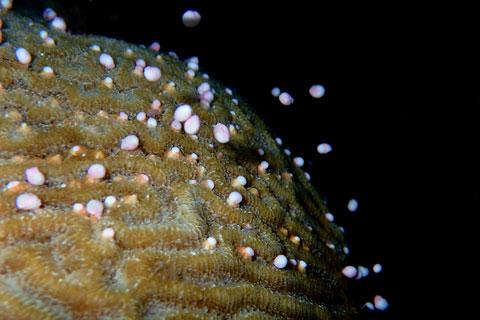

She, of course, is talking about coral spawning, the process that occurs only a few times a year when coral colonies, on cues from the lunar cycle and water temperature, release millions of their tiny eggs and sperm—collectively called gametes—into the sea.

“We had the most prolific spawn I’ve ever witnessed from elkhorn corals,” she recalled of the event at Elbow Reef two months ago. “We collected gametes from 13 colonies, with each representing their own unique genetic entity. They were a mix of colonies that grew there naturally, plus a few that had been outplanted as part of a reef restoration effort many years ago.”

Elkhorn corals, like many other species, are hermaphrodites that release both eggs and sperm from the same colony. The specimens Williamson and her team harvested that night with special nets were transported back to the Coral Reef Futures Lab at the Rosenstiel School for experimentation.

Coral spawning is the heart of her research. She became enamored by the intricate underwater ecosystems while snorkeling in Panama as an undergraduate at Barnard College, marveling at the diverse species that make reefs their home.

She knows that coral reefs in oceans around the world are under attack, their populations dwindling as climate change accelerates a process called coral bleaching.

From Belize to The Bahamas to Florida, bleaching events have hit coral reefs hard, according to Williamson. Even Australia’s Great Barrier Reef has been decimated, something many people thought would never happen. “They thought it was invincible, that it could never be threatened because of its immense size,” she said. “But marine heat waves have been occurring more and more frequently and have already, in the last five years, killed about half of the corals there.”

She and her colleagues are trying to save coral reefs from extinction. One particular strategy they are trying: manipulating the algae that corals host.

“Much like we have all kinds of bacteria and microbes in our gut that live symbiotically in our bodies and enable us to perform essential functions, corals have similar associations with microbes that live inside of them, including symbiotic algae. And it is that association that breaks down when a heatwave comes through,” Williamson explained. “As ocean temperatures rise, corals expel the symbiotic algae living within their tissues and turn white. In such a state, they essentially starve, as they lack energy supplied by algae. Many never recover.”

A ‘vaccine’ for coral reefs

So, Williamson is giving corals what might be described as a much-needed shot in the arm, providing lab-raised coral babies with a thermally tolerant type of algae in the hopes that it will make them resistant to bleaching events once they are planted on a reef.

Most coral juveniles, she explained, are born without algal symbionts, acquiring them within the first few weeks of life. And that’s why Williamson’s coral gamete harvesting trips to reefs from Miami to the Florida Keys to the Caribbean are so important. “It’s a great opportunity to intervene,” said the Ph.D. candidate, who works primarily with elkhorn, mountainous star, and brain corals.

The coral larvae she collects are raised and nurtured in tanks, getting a dose of the heat-resistant algae that can be grown in the lab or harvested naturally from the ocean. “I like to think of it as a vaccine,” she said.

The specimens she helped collect from Elbow Reef back in July are now eight weeks old—happy, healthy, and growing in the lab. “They recently acquired their first thermally tolerant symbionts,” Williamson said.

Her research suggests the strategy could work. In a recent study she led, lab-raised mountainous star coral treated with heat-resistant algae survived twice as long in water temperatures of about 93 degrees Fahrenheit than corals hosting little or none of the robust algae. Now, the challenge will be planting the corals on a reef to see if they can survive heat waves in the ocean.

In the days ahead, she and a group of other coral researchers will head out to Rainbow Reef off Key Biscayne for another potential spawning event—their underwater flashlights illuminating not only the reefs but also bioluminescent creatures lighting up like little Christmas trees and octopuses scouring the seafloor for food.

They’re hoping to witness another aquatic show for the ages that Williamson describes as being inside a giant snow globe. But if it doesn’t happen, there’s always the lab. Researchers are using a relatively new technique to coax corals into reproducing in a controlled environment, setting up special tanks that mimic the ideal conditions for sex on the reef: 85-degree ocean temperatures and full moon illumination. “And that helps to take some of the guesswork out of it and ensure that we get lots of coral babies,” Williamson said.

Raising coral babies with thermally tolerant algae is just one aspect of her research. Williamson is also targeting corals in the ocean that have survived marine heat waves and disease outbreaks. Those corals will serve as parents for selective breeding efforts, helping to create new generations of heat-tolerant and disease-resistant reefs.

She also cryopreserves coral sperm, creating a genetic bank for future selective breeding. Williamson’s colleagues in the lab call her “coral mama.” But she doesn’t mind. She’s helping to save the rainforests of the ocean.

“Liv’s work has really helped build the portfolio of coral research at Rosenstiel and allowed us to grow in new directions, especially with respect to coral spawning and reproduction,” said Andrew Baker, a professor of marine biology and ecology, who heads the Coral Reef Futures Lab. “She began the first genetic banking effort for corals in our area, and this is leading to many new projects such as selective breeding, which will enhance our efforts to build climate resilience on Florida’s coral reefs.”

Team effort

Her research complements other coral restoration efforts underway at the University. For example, a first-of-its-kind, three-year project to restore coral reefs in two South Florida counties is ongoing. The Southeast Florida Coral Reef Restoration Hub, established by the Rosenstiel School with a $6 million grant and supported by funding from the University’s Laboratory for Integrative Knowledge, is restoring 125 acres of reef habitat in Miami-Dade and Broward counties by growing and planting more than 150,000 coral colonies and juveniles from five coral species, three of which are threatened.

Rosenstiel School researchers Andrew Baker and Diego Lirman are leading the initiative. They are partnering with the College of Engineering, Rosenstiel School oceanographer Brian Haus, Nova Southeastern University, SECORE International, the Florida Aquarium, and the Phillip and Patricia Frost Museum of Science.

A world without coral reefs would be a world in peril, Williamson believes. “Coral reefs are home to a quarter of all marine species. If we didn’t have them, we wouldn’t have the rich diversity of marine life that all depend on these ecosystems at some point in their lives,” she explained. “And that would have huge consequences not only for the biodiversity of the ocean but also for humans—on our economies, on our ability to feed ourselves, and in the way coral reefs protect our shorelines.”

She is helping to raise awareness about coral reefs; participating in citizen science expeditions as part of the Rescue a Reef program; and engaging local, public, and private school groups in hands-on activities during a Women in Science Day.

“As scientists, we can implement intervention strategies to create strong, new generations of corals. But none of our work really matters if we don’t get the public on board with it,” Williamson said. “And we need government to enact polices that address the root causes of climate change so that our children will be able to see a coral reef 50 years from now.”