With a plume of white smoke generated by its solid fuel-powered motor, the Ibis 1 blasted off from its launchpad and rocketed skyward at nearly 380 miles per hour, carrying with it the hopes of a University of Miami team of aerospace engineering students who are aspiring to greater heights.

Their 10-foot-long streamlined vehicle, built in labs at the College of Engineering, soared higher than three Empire State Buildings combined, plummeting back to a field just outside Tampa, Florida, as two parachutes slowed its descent.

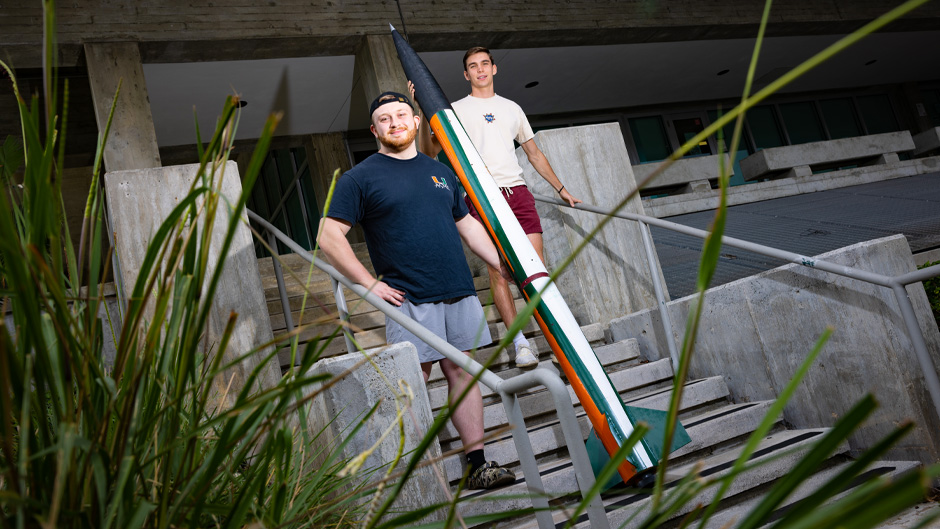

Mission accomplished. “All that awaits now is one more critical test,” Matthew Burian, project manager of Rocket ’Canes, one of the more than 50 teams competing in the college and university division of NASA’s 2023 Student Launch Challenge, said following the February launch. Part of the space agency’s Artemis Student Challenges, the nine-month-long competition requires teams to design, build, and fly a high-powered amateur rocket to an altitude between 4,000 and 6,000 feet.

Teams must successfully complete a series of challenges. The “critical test” to which Burian refers is a second flight demonstration late this month on farmland in Plant City, Florida, where this time, the reusable Ibis 1 craft must not only launch and land, but deploy its payload: a digital camera that will emerge from the nose cone upon touchdown and take pictures of the surrounding terrain.

If all goes well, the team could secure a spot in the finals near NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, that will occur from April 13 to 15.

That Rocket ’Canes is even competing in the contest is an achievement. The club had literally been mothballed during the height of the pandemic, a time during which its senior members graduated from the University, taking their knowledge and rocket-building skills with them.

But when Burian and club president Tristan Peterson—both aerospace engineering majors—stepped into their leadership roles last year at a time when pandemic protocols began to wane, they made it their mission to resurrect the club, deciding that the Student Launch Challenge would be an ideal opportunity to do so.

“The whole premise of our club had been working on rockets and competing in competitions. But last year, with a lot of our seniors graduating, we wanted to transition to a competition more focused on learning,” Peterson said. “NASA Student Launch was the best fit because it focuses more on the whole process as opposed to just the product. So, we sent in our proposal and got accepted.”

The team passed its first test last December, building a 6-foot-long subscale rocket and successfully launching it 1,000 feet into the air. “That was our proof of concept that we were capable of building and launching a rocket as a team,” Burian said. “We launched three days after fall semester finals and submitted a written report to NASA.”

Construction on Ibis 1 started in mid-January, with team members using a software program to simulate launches before the building phase started. While some components were purchased commercially, other integral parts of the payload, including a scissor-lift device that deploys the digital camera, were 3D printed at the Johnson & Johnson 3D Printing Center at the College of Engineering. Team members also used the college’s machine shop to create parts.

Ammonium perchlorate fuels the rocket, while two onboard altimeters record its altitude and velocity, and a GPS device tracks its position.

Ibis 1 completed its maiden flight on Feb. 18 just outside Tampa, soaring to nearly 4,000 feet. But like some NASA rockets that lift off from Cape Kennedy, the mission was not without its problems. As team members began to assemble the rocket at the launch site, Burian realized that he had forgotten to bring the O-rings that seal the motor and prevent hot gases from reaching other parts of the rocket. “If we don’t have those O-rings, we don’t launch, and we’re out of the competition,” Burian said.

Other teams were willing to help, but they had no O-rings to spare. Then, finally, the break Burian, Peterson, and the other members of the Rocket ’Canes team needed: A local rocket-building hobbyist observing the competition had the coveted O-rings they needed. The only catch was that they were sitting in his home’s garage miles away.

With just three hours before Ibis 1 was scheduled to blast off, Burian and a group of other team members raced to the man’s Tampa-area home, retrieving the O-rings before returning to the launch site. But even then, it still wasn’t smooth sailing. The team had to use sandpaper and a rubber mallet to ensure two other critical parts of the rocket's motor would fit properly.

“We really had to overcome a series of problems that day. But all said, it’s getting 25 busy college students to work together and writing 150-page reports on our rocket’s performance that proved to be the hardest part of this competition,” said Peterson, noting that students from other University of Miami schools and colleges are members of the team.

Both Peterson and Burian credit their mentor, Jimmy Yawn, who has over 40 years of experience in high-powered rocketry, as being instrumental in the team’s success.

Along with building a complex rocket and payload and undergoing detailed reviews and evaluations, the team is also required to conduct community outreach. As such, they have taught eighth graders at MAST Academy on Virginia Key how to use software programs to design and build amateur rockets.

Should the team make it to Huntsville, 15 members will travel to the site, each with a different responsibility—from rocket recovery to safety protocols.

Burian, who used to build rockets with his father while growing up on Rhode Island, considers the NASA Student Launch Challenge to be a steppingstone to bigger things. “It’s an exciting time to be going into this industry,” he said. “After the Apollo program, it’s finally starting to pick up again, so that’s really cool.”