With forecasters predicting an above-normal Atlantic hurricane season for 2024, a new hurricane forecast model that was put into operation last year will face a stern test of its capabilities this season.

Scientists at the University of Miami Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies (CIMAS), operating out of the Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric, and Earth Science, worked with researchers at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to develop the Hurricane Analysis and Forecast System (HAFS).

HAFS ran alongside existing models as an experiment in 2022 for the National Hurricane Center, and this summer it is being made one of NOAA’s official hurricane forecast models.

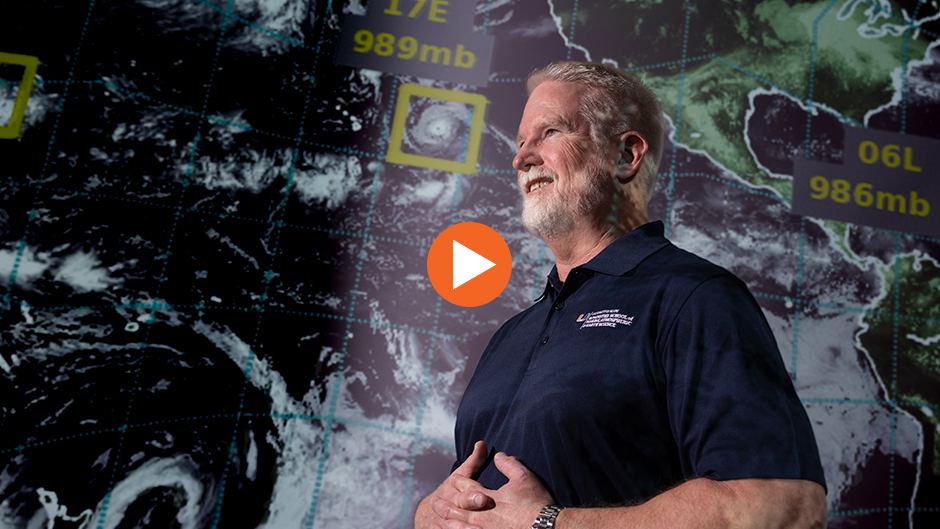

William Ramstrom, a senior software engineer at CIMAS, who has been working to develop HAFS for the past five years, answered questions about what makes HAFS so effective and how the model will be upgraded in the future.

How many versions of HAFS are there?

HAFS is NOAA’s newest operational hurricane model. Version 1.0 went into operations in June 2023, and version 2.0 is planned to go into operations this summer in early July with upgrades to model initialization and model physics to continue to improve the accuracy of track and intensity forecasts. NOAA runs two different configurations of the HAFS model, as well as the legacy Hurricane Weather Research Forecast (HWRF) and the Hurricanes in a Multi-scale Ocean-coupled Non-hydrostatic (HMON) models for a total of four different models. This suite of models gives forecasters better diversity of forecasts, which can be useful for difficult forecast cases. The forecasters can also leverage their many years of experience with the legacy HWRF and HMON models and compare their forecasts with those from the newer HAFS model.

What makes HAFS so effective? Why is it so good at forecasting storm intensity and better than previous models at predicting rapid intensification?

HAFS uses several techniques to improve forecasts above prior models. To better capture the details of hurricanes, it uses higher model resolution in an area around the storm center. This nested grid follows the storm as it moves across the ocean to better simulate the physical processes in the eye and eyewall of the hurricane. The effect is akin to the benefit we see with the increase in megapixels in our phone cameras—smaller details are more accurately captured. This is important both for forecasting the track and intensity of the storm at its earlier stages and for resolving the storm hazards as it makes landfall.

The team of scientists at NOAA and CIMAS at the Rosenstiel School have collaborated on improving the handling of physical processes at sea surface under hurricane wind conditions, and the details of how rain and ice behave in clouds aloft. These are important factors in accurately forecasting hurricane intensity. Additional work was done to ingest observations from the surface, satellite, and NOAA P3 reconnaissance aircraft to start the model with more accurate views of the initial weather conditions.

What major upgrades will HAFS undergo over the next four years?

Our team at NOAA and CIMAS continues to add new features and upgrades to HAFS. We are currently testing a basin-scale version of HAFS. This will cover the full geographical bounds of the North Atlantic hurricane basin with the capability of modeling several storms at high resolution in the same model run. Earlier research with the Hurricane Weather Research Forecast model showed that this improves forecast accuracy during busy parts of the season when multiple storms are active, affecting one another. We plan to run an experimental version of this code during this summer on our research supercomputer to learn what further improvements are needed before it can go into operations in coming years.

Our colleagues at NOAA in Washington, D.C., have begun experimenting with running HAFS in ensemble mode, generating about 20 different forecasts from slightly different starting conditions. This technique can provide important information to forecasters on the uncertainty about a hurricane’s track and intensity. As computational power continues to increase, we will also investigate moving to higher model resolution as another way to improve forecasts.

Forecasters are predicting an above-normal Atlantic hurricane season for 2024. How did HAFS perform for the 2023 season? Also, can it be used to produce forecasts for the Pacific hurricane season?

We are ready to run HAFS again this summer to cover all the expected activity. Two operational versions will be run, and our researchers will also be testing several new configurations in near real-time. If those research configurations perform well, their changes will be put on the path to transfer into official operations in upcoming years.

HAFS performed very well for the 2023 season, generally 10 percent to 15 percent better for track and intensity by forecast days 3-5 than the previous hurricane model. HAFS and the other models did very well forecasting the landfall of Hurricane Idalia in Northwest Florida last August, and it accurately captured several instances of rapid intensifications of hurricanes offshore.

As with all models, there is still room for improvement. For Hurricane Otis, which made a devastating strike on Acapulco, none of the models did a great job, though some cycles of HAFS were closer to reality than other models. Researchers at NOAA and CIMAS are looking into how the model initialization and physics can be improved to better forecast rapidly intensifying storms like Otis in the future. NOAA runs two versions of HAFS for the North Atlantic and East Pacific hurricane basins. It also runs one version of HAFS for all the other tropical cyclone basins around the world, capturing typhoons in the West Pacific, cyclones in the Indian Ocean and Arabian Sea as well as tropical cyclones in the Southern Hemisphere basins including around Australia. These model runs are used as guidance by the forecasters at the National Hurricane Center here in Miami and at the Central Pacific Hurricane Center and Joint Typhoon Warning Center, which are both located in Honolulu.