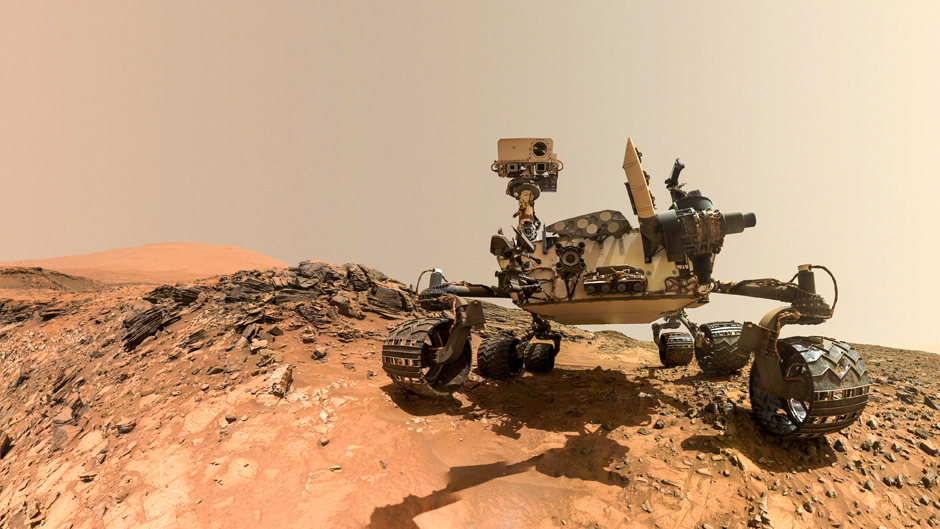

Curiosity didn’t kill the cat in this case. Instead, NASA’s 1-ton rover, which for the past 12 years has been searching for the building blocks of life on Mars, discovered something never before detected on the red planet: pure sulfur. And it all happened by chance.

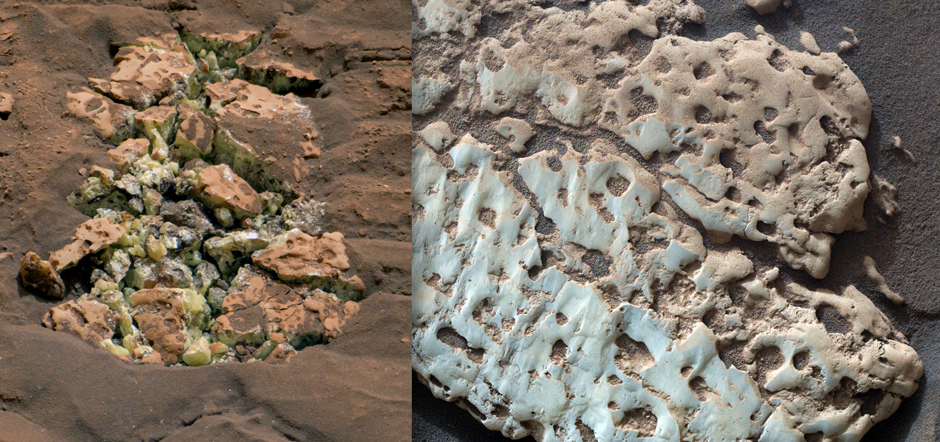

While exploring Gediz Vallis, a channel that winds down part of the 3-mile-tall Mount Sharp in the center of the Gale Crater, the six-wheeled Curiosity rover drove over a rock and cracked it open, revealing yellowish-green crystals of the chemical element.

The rover, which is about the size of a small SUV and is equipped with 17 cameras, had already discovered sulfur-based minerals on Mars. But the recent discovery of elemental, or pure, sulfur on the red planet was a first. And the rover found an abundance of the stuff—a field of rocks similar in appearance to the one Curiosity crumbled.

“Finding a field of stones made of pure sulfur is like finding an oasis in the desert,” said Ashwin Vasavada, Curiosity’s project scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California. “It shouldn’t be there, so now we have to explain it.”

Discovering the unexpected “is what makes planetary exploration so exciting,” Vasavada added.

But what could the presence of pure sulfur on Mars possibly mean?

“Anything,” said Carl D. Hoff, a professor in the Department of Chemistry in the University of Miami College of Arts and Sciences, who has worked with sulfur extensively. “It could even be the case that it came from a meteorite shower; elemental sulfur is often found in rocks from meteors.”

Curiosity’s groundbreaking discovery evoked fond memories for Hoff, who as a little boy, would conduct experiments with sulfur in his home.

“Utilizing a late 1950’s Gilbert Chemistry Set, I was a good character match for Steve Urkel of Family Matters,” he recalled. “Real chemicals were involved, and it was removed from the shelves later, but not before I had caused evacuation of our house on several occasions due to experiments in burning sulfur and reacting it with different metals.”

Described as essential to all living things, sulfur is an important element for several reasons, Hoff noted.

“Flexibility and versatility are what sulfur brings to the table,” he said. “It is in several key proteins. It binds important metals like molybdenum in the liver enzyme xanthine oxidase and the nitrogenase enzyme in the roots of plants. Oxygen is directly above sulfur in the periodic table, and O is ‘hard’ as opposed to S being ‘soft.’ S binds very strongly to metals, which is one reason it has to be removed from gasoline. It will bind to platinum and palladium and rhodium in the catalytic converters of cars and so must be removed prior to burning. It also is a good binder of mercury, Hg. Your hair contains a lot of cysteine, which is a protein that contains S. If you eat fish with a lot of mercury in them, they can detect it in your hair where the cysteine protein binds it very strongly.”

Hoff admits that his initial reaction to hearing the news that pure sulfur had been found on Mars was that the discovery was “much ado about nothing much.”

“The most significant result is being able to go to Mars and operate equipment remotely and that this leads you to find a pretty rock that contains S8 yellow sulfur just like in the Gilbert Chemistry set,” he said. “It has been known for some time that this was probable, and now it is proven. The joy of the scientists who remotely controlled this is real and justified but more for the technical skill and not the rock they found.”

He applauded the ingenuity of NASA engineers, calling their ability to drive a rover on another planet millions of miles from Earth “a great achievement.”

“China recently sent a mission to Mars as well, and its rover got stuck but not before it proved that water might have existed there 400,000 years ago,” Hoff said. “I hope that this work is followed up in 40 years.”