It’s now officially over, leaving in its wake a trail of devastation, death, and massive economic losses.

And while the 2024 Atlantic hurricane season didn’t quite live up to some forecasts that predicted as many as two dozen named storms, it is still one for the record books. The Atlantic basin saw 18 named storms, with 11 of those becoming hurricanes and five intensifying into major hurricanes. Five hurricanes made landfall in the continental U.S., with two of them being major cyclones.

The season actually got off to a slow start—in fact, its slowest since 2014.

The first named storm didn’t form until June 19, when Tropical Storm Alberto formed in the western Gulf of Mexico, making landfall on the northeastern coast of Mexico the following day.

Then came Beryl, which became the earliest Category 5 hurricane to form in the Atlantic Ocean, doing so two months before the season’s peak.

![]() “Not only was Beryl a rare June hurricane that formed from an African easterly wave, but it went on from there to break a handful of related records, stretching the bounds of what the early part of the season is capable of,” said Brian McNoldy, a tropical cyclone expert and senior research associate at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric, and Earth Science.

“Not only was Beryl a rare June hurricane that formed from an African easterly wave, but it went on from there to break a handful of related records, stretching the bounds of what the early part of the season is capable of,” said Brian McNoldy, a tropical cyclone expert and senior research associate at the University of Miami Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric, and Earth Science.

Beryl struck the island of Carriacou as a Category 4 hurricane on July 1. It later strengthened to a Category 5 cyclone in the Eastern Caribbean Sea. After weakening only slightly, it passed just south of Jamaica as a Category 4 hurricane on July 3, then made a second landfall on the Yucatán Peninsula. It was a Category 1 hurricane by the time it hit Texas—its final landfall—on July 8, spawning some 68 confirmed tornadoes across several states.

The storm, it seemed, was a sure sign that the forecasts of an extremely active hurricane season were spot on.

Roaring back to life

But then something unusual occurred. The tropics suddenly turned quiet at a time when hurricane season is typically at its peak.

The positioning of a weather phenomenon known as the Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO) was the reason, according to Ben Kirtman, a professor of atmospheric sciences and the William R. Middelthon III Endowed Chair of Earth Sciences at the Rosenstiel School.

“It covers the entire tropics and has two phases to it,” Kirtman said of MJO, an eastward moving disturbance of clouds, rainfall, winds, and pressure that traverses the planet in the tropics and returns to its initial starting point in 30 to 60 days.

“In one phase, half the globe is in a state where storminess and convection are enhanced in the tropics, while the other half is in a pattern where there’s a lot of suppression and drought conditions,” Kirtman explained. “So, during that peak-season, that Madden-Julian Oscillation was very active, and we were in that suppressed phase, and it curtailed a lot of the storm development for a significant period. Many people thought the forecast was a bust for an active hurricane season. But once the MJO pushed through, things lit up again.”

Indeed, the season roared back to life with a record-breaking ramp up following its peak-season lull.

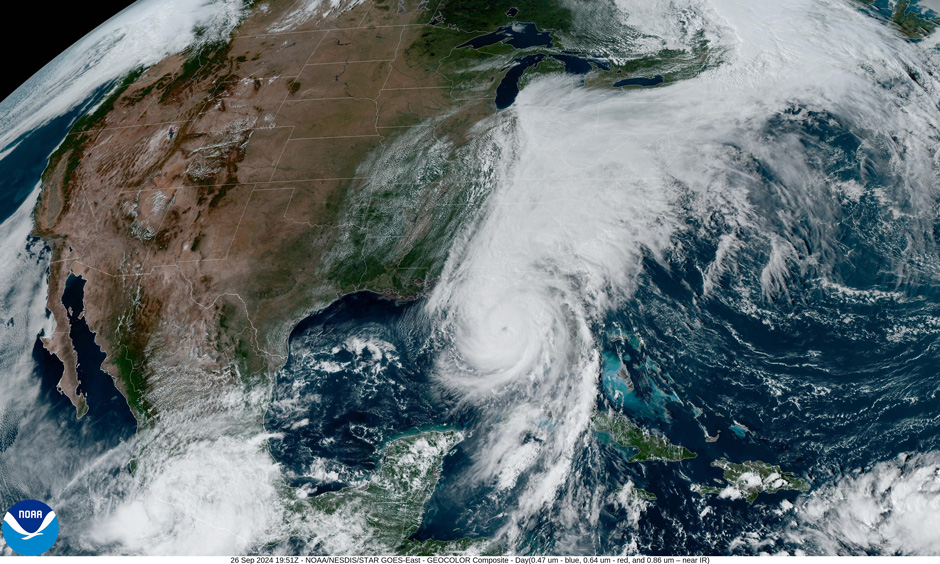

Powerful Hurricane Helene made landfall on the Florida Gulf Coast as a Category 4 storm on Sept. 26, causing catastrophic flooding across the southern Appalachians, widespread wind damage from the Gulf Coast to the North Carolina mountains, and storm surge flooding along portions of western Florida. The storm killed more than 200 people along its path.

Milton made landfall as a Category 3 hurricane near Siesta Key, south of Tampa Bay, on Oct. 9, causing widespread damage across Florida with deadly tornadoes and storm surge. The storm’s rate of rapid intensification—a 90-mile-per-hour increase in wind speed during a 24-hour period from early Oct. 6 to early Oct. 7—was among the highest ever observed.

Warm Gulf waters

Could warm water eddies, which can supercharge hurricanes, be responsible for Milton’s rapid intensification? Perhaps, according to Lynn “Nick” Shay, a professor of oceanography at the Rosenstiel School.

“There was a lot of eddy activity in the Gulf this summer, and those eddies seem to be carrying more thermal energy than they were 10 or 15 years ago. And that’s based on satellite data and available in-situ measurements from floats and other instruments,” said Shay, who, as part of his research, deployed about 70 Airborne EXpendable BathyThermograph, or AXBT, instruments into Gulf waters for hurricanes Helene and Milton this season.

“It seems to be a new paradigm,” Shay said of increased storm activity in the Gulf. “When you look from 2017 to now, we seem to be having significant storms in the Gulf. Usually, it was rare to have a Category 5 storm in the Gulf, but now we’re seeing more and more.”

As such, the Gulf Coast again bore the brunt of the season’s most powerful cyclones, with five hurricanes—Beryl, Debby, Francine, Helene, and Milton—making landfall along that coastline.

“That’s a lot, but not quite a record. There were also five in 2005 and 2020, and then the record-holder is 1886, with six of them,” McNoldy said. “The U.S. East Coast has been relatively spared. A couple of recent hurricane landfalls from storms that came directly from the Atlantic include Nicole in 2022 and Isaias in 2020. But if we narrow the search to Category 3-plus hurricanes, the last east coast one was 20 years ago: Jeanne in 2004. In those same two decades, the U.S. Gulf Coast has experienced 16 major hurricane landfalls. The reason for this huge disparity is probably part luck and part large-scale steering patterns. It would take some digging into data to arrive at a solid answer.”

And as if the catastrophic loss of life and economic impacts caused by such storms were not enough, the potential remains for Florida’s west coast to experience another massive outbreak of red tide exacerbated by the storms that churned ocean waters in the Gulf this season, Shay believes.

In previous research, Shay found that devastating outbreaks of Florida red tide—which occurs when microscopic algae multiply to higher-than-normal concentrations, often discoloring the water—seem to follow the passage of powerful hurricanes over the Gulf of Mexico.

“The fundamental problem is when you have hurricanes on the order of a Helene or a Milton or any storm that reaches Category 3 or 4 status and moves slowly, you’re going to get a lot of upwelling of ocean waters. So, there’s a potential for those waters to impact the ocean’s food chains,” said Shay, who is currently on Florida’s west coast and has noticed hotspots for red tide.

Brendan Turley, a NOAA affiliate of the Southeast Fisheries Science Center and an assistant scientist at the University of Miami’s Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies, said there is little direct evidence that hurricanes directly cause red tides. “However, there are several cases in which hurricanes have indirectly affected them,” he said. “Hurricane Michael in 2018 and Ian in 2022 seemed to stir the pot on red tides that existed prior to both storms. Similarly, this year, a budding red tide existed prior to Hurricane Helene, and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission has now been monitoring an on-going, but relatively minor red tide.”

Turley said the mechanism is not upwelling, “but rather nutrient runoff from the rain and storm surge washing all the stuff off land into the coastal ocean.”

The start of the 2025 Atlantic hurricane season is just five months away. What it will bring remains to be seen.

One burning question: Could we be experiencing a new normal as far as record-breaking storms that are getting stronger because of climate change?

“Possibly,” said McNoldy, who completed his 29th year writing online updates of tropical storm activity in the Atlantic. “Climate change certainly has its fingerprint on everything in the atmosphere, but hurricane-related signals are harder to tease out because of the relatively short period of reliable data and significant interannual variability.

“But more and more studies are showing evidence in recent decades of two changes: higher peak intensities and a higher frequency of rapid intensification. So, not necessarily more storms, but of the ones that form, they are becoming more likely to become stronger and sometimes in less time,” he said. “I don’t ever point to climate change as the singular cause of anything when it comes to hurricanes, but it’s gradually nudging their behavior, on average.”